Majid Sheikh

It was in the 1920s that every morning a group of youngsters would leave together for school Kucha Chabaksawaran, inside Lahore’s Mochi Gate, located towards the edge of Rang Mahal, who half a century later would become the sub-continent’s leading intellectuals, each in their own right.

Just imagine four schoolboys emerge from the house of Maulana Noor Ahmed Chishti, the renowned writer of ‘Tehkeqat-e-Chishti’, they being Pakistan’s finest psychologist, Dr Muhammad Ajmal Makhdoom, Dr Ahsanul Islam the famous zoologist who almost won a Nobel Prize and his brother the air force pilot Anwarul Islam, who fought in the 1967 Middle East War and is mentioned in Israeli accounts as the most dangerous man best avoided, and lastly Mr Abdul Hamid Sheikh, the journalist and Editor of the C&MG known famously in Lahore as HS. The mothers of these four were sisters and circumstances had brought the cousins back to their grandfather’s house. All of them went to Central Model School.

From nearby they were joined by the great short story writer Rajinder Singh Bedi. Then emerged from a neighbouring house the great historian and journalist Abdullah Malik and his brother Rauf Malik. They were joined by brothers Medjid and Hameed Almakky, publishers and among the social elite of old Lahore. Sometimes they were joined by a student from the house of the great artist Abdul Rahman Chughtai. In those days the young boys walked to their schools together. Along the way they greeted every elder they crossed, for then they recognised all of them. Each one of these famous names deserve a column on their own, such was the role they played to make Lahore what it became. But in this column we will dwell on the life and times of Abdullah Malik.

Abdullah Malik was born on the 20th of October, 1920, in Kucha Chabakswaran. After learning the Quran at home he was admitted to the Mission High School at Rang Mahal. This was the first English-medium school set up in Lahore after British takeover in 1849, and was in its days the finest.

From there he got admitted to Islamia College on Railway Road.

He belonged to a very religious environment, as were the rest of those youngsters who trudged to school every day then. The Chishti and the Almakky households were known for their religious piety and scholarship, as were the Maliks and Chughtais. Abdullah Malik set off to become a teacher and given his religious scholarship he joined the ‘Tehreek-e-Ahrar’, which with time was becoming extremely communal. The young Abdullah started to avoid their meetings, and after considerable discussion with his friends he joined the Communist Party of India. His commitment to a secular way of life, to tolerance, social justice, to democracy and to scholarship remained with him till his dying day in April 2003.

He started his journalistic career by editing the Islamia College magazine. Among his class-fellows was the Kashmiri politician Sheikh Abdullah and Chaudhary Rehmat Ali, the man who coined the name ‘Pakistan’ while at Cambridge. In essence Malik was anti-imperialist and secular, and because of these traits he joined the Communist Party newspaper ‘Qaumi Jang’ and advanced the message of independence for his homeland from colonialism.

During the Second World War, the CPI decided to oppose the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini and once the war was over to push for independence. But given the communal path that Nehru’s National Congress was taking in negotiations with Jinnah’s Muslim League, it was clear the Pakistan promised to be a land that was “secular, tolerant, democratic and socially just”, very much how Abdullah Malik was to describe Jinnah in his writings. So Jinnah and other communists opted for Pakistan, letting go of the dream of a united India.

Sadly, by the time he passed away at the age of 82, he was to see an “extreme communal military-mullah controlled Pakistan”, quite the opposite of what he till his dying day stood for. His fearless nature and his outspoken views remained his trademark. After 1947 the communist newspapers were closed and Abdullah Malik was arrested and spent three months in the notorious dungeons of the Lahore Fort. He was released on the condition that if he continued to propagate his views, he would have to endure further torture and imprisonment.

In 1951 the government of Liaquat Ali Khan started arresting members of the CPP for planning a coup, and in the infamous Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case, journalists like Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Mazhar Ali Khan were jailed. At this stage to keep the struggle going Abdullah Malik joined the daily ‘Imroze’, an Urdu newspaper founded by the Marxist freedom fighter Mian Iftikharuddin, who had with Jinnah’s assistance also founded the daily ‘The Pakistan Times’. His column soon found his name being mentioned among the top journalists of Pakistan. By this time he was working with exceptional writers like Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi and Sibte Hasan, and their influence on him was considerable.

As ‘The Pakistan Times’ influence grew, he in the late 1960s served as the London correspondent of ‘Imroze’ and ‘The Pakistan Times’. By this time the military government of Gen. Yahya Khan had denied the winners of the 1970 general elections their right to form the country’s government. On his return to Lahore in 1971 he was again arrested and jailed. He was among the very few Pakistani intellectuals who openly sympathised with the Bengali democratic position, and went as far as supporting the independence of East Pakistan in the form of Bangladesh. For this and for his opposition to the ‘planned’ hanging of Sheikh Mujib, he was sentenced to whipping. This luckily was never carried out. “There is no way for any fair person to support the political corruption and military dictatorship of Pakistan”, he was to say.

His trade union activities saw him, and a number of his colleagues, being dismissed from ‘Imroze’. But with two of his friends he set up a national daily newspaper titled ‘Azad’. But because of military threats and advertisers being warned, it closed once the military action started in East Pakistan.

But all these setbacks did not deter the free spirit of Abdullah Malik, who started off on a career of writing a history of Pakistan and other aspects of sub-continental issues. His books on the history of Punjab are masterpieces in their own right. Being an established columnist, and now also a respected historian, he started writing a column in the right-wing Urdu newspaper ‘Nawa-e-Waqt’. His dialectic approach soon made his the most read column in the newspaper.

On Christmas Day of 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed, and this was a blow for the committed Communist that Abdullah Malik was. The coming to power of Gen. Musharraf led him to write an excellent book on the history of military takeovers in Pakistan. He was of the considered view that military generals have, and never can, understand the damage they do by grabbing power. He was convinced that military dictators are natural enemies of democracy, which leads them and “their political lackeys to nurture corruption in all its forms”. His deep understanding of the praetorian mindset led him to write a number of books on the subject.

So on the 10th of April 2003, the great Abdullah Malik passed away in an Islamabad hospital. He was to write in his book ‘Purani mehfilain yaad aa ra’hi ain’: “I have spent my entire life committed to the beliefs of one day establishing a Socialist Pakistan, where the love of mankind transcends all religions, faiths and creeds”. Sadly, that day is still far away.

Source:

Dawn, January 14th, 2018

HISTORY OF MOHALLA CHABUK SAWARAN –

ANCESTRAL HOUSE OF M.A. RAHMAN CHUGHTAI

Centuries of historical names and incidents

Lahore is a strange city. It has everything historical attached to it. Take the Mohalla Chabuk Sawaran inside the city. Maulvi Ahmad Baksh Yaqdil (18th-19th century), explains the area as:

“Diwar khana Faqeer Khana waqia Darul Sultanat Lahore; Mohalla Qazi Saderuddin Marhoom; Havelli Adina Beg Khan; Guzar Chabuk Sawaran, Kakey Zai; Mutasil Kocha Allama Hazrat Muhammd Sharyar Maskoor Lahori; Mutasil Masjid Chinay Wali, mubia Bahadur Shah Alamgeer Badashah; Feil Khana Shahnawaz Khan; Takia Sadoan; Katra Haji Amanullah; Chotta Mufti Baqir, etc.”

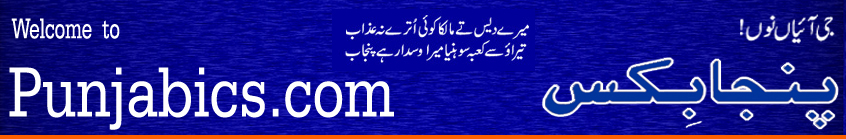

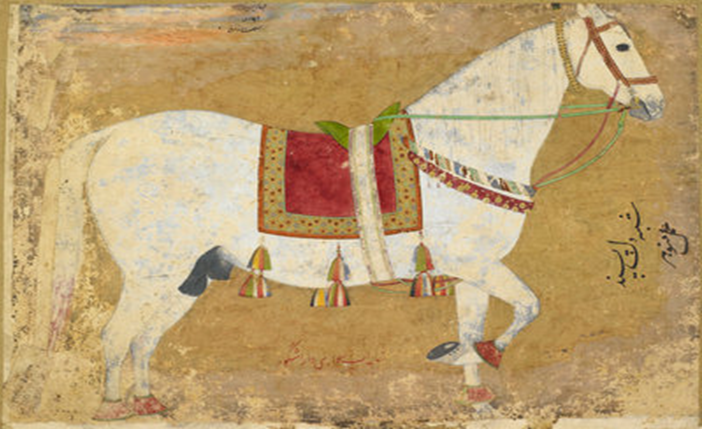

Dil-Pasand horse of Dara Shikoh

What exactly is KOCHA CHABUK SAWARAN? The dictionary defines Kocha as a Galli, guzargah, or piece of land as “Bara” or exhibition centre. We know that the word Chabuk Sawaran is obviously HORSE RIDERS and what had the horse riders in common with this Bara of land. We know there was a market place for horses outside Taxalli Darwaza Lahore, as well a market of horses outside Delhi Darwaza,. But this is inside the city itself. It means an exhibition ground or a stable, enclosure of horses. And with the Mohalla are the few house attached to its exhibition place of horses there. They must be even giving performances of some kind.But the other names are all historical.

Neighbour hood of Kocha Chabuk Sawaran

Qazi Saderuddin was the Qazi at the time of Emperor Akbar, who rebelled against the religious policies of the Emperor. He was very popular with the people and could not be handled in a drastic way. So Emperor Akbar had him expelled from the city forever. A rebsel scholar in all cases.

Allama Shahryar was Imam of the Wazeer Khan Mosque, and he too rebelled against Ahmad Shah Abdalli, and openly insulted the King for his actions. Abdalli said his prayers behind him and could say nothing to him.

Adina Baig Khan was of course for some time Governor of Lahore and part of the conspiracy in the Abdalli and the Mughal period of Lahore. A very interesting figure who got married in Lahore to a Syedzadi of this Mohalla and later divorced her for fear of marriage to a Syed family.

There are a few Shahnawaz Khans in the Mughal period. Mufti Baqir was of course a Mufti of Lahore in the times of Emperor Shah Jahan and there is a Chotta Mufti Baqir still named after him in Lahore. Haji Amanullah may be many persons.

Masjid Chinay wali is the famous mosque in the Mohalla, now totally destroyed and rebuilt. But very strangely Yaqdil associates it to Bahadur Shah, Shah Alam, son of Aurangzeb Alamgeer. Sadoos were famous for residence in the city area and were responsible for publication houses, publishing old manuscripts in book forms.

In Mughal time the FEIL KHANA means there was a stable for elephants in this very area. Elephants traversing the Mohalla would be a unique sight under any circumstances.

Yaqdil associates Chabuk Sawaran with ethnic Kakay Zais, but there is much more to it. Documents prove the transfer of some horse dealers from Kanpur in India to this Mohalla in 1855 extra.The names of them are known, and some of them were highly educated and could even write in English. These horse dealers had bought portions of Mian Khan Havelli. Afzal Khan had two wives Noor Jan and Mahbub Jan., He died and these two ladies sold the property.

Nur Khan Herawi Chabuk Sawar Lahore

Recently a group of documents have been discovered which shows us more dtails of the horse riders. We have a Bakatarabu Begum along with a registrar Abdur Rahman Khan Afghan settled in the city of Kanpur (now in India) in 1855. Then we have references of Qasim Khan son of Munawar Khan Afghan again in Kanpur in 1870. Then we find them shifting to Havelli of Mian Khan and we hear of Afzal Khan and Wazeer Khan Pathans. We hear of Bobo Begum wife of Afzal Khan as well as two other ladies later, Noor Jan and Mahbub Jan, widows of Afzal Khan. Then we hear of Akbar Khan, son of Afzal Khan, who signs himself as a horse dealer in English. Then the havelli is bought by a certain J Rustam, who signs an affidavit of two pages, handwritten completely in English language. That means the horse dealers were educated people. The final transfer is dated around 1915. That is one family of Chabuk Sawars in the Mohalla, and they had a stable and a ground to show of their horse stock and it was called Kocha Chabuk Sawaran. Thats history in full!

Havelli Mian Khan of course is RANG MAHAL or the havelli of Nawab Lutufullah Khan son of Nawab Saad ullah Khan, Prime Minister of Emperor Shah Jahan.

It boggles the mind as to the kind of historical personages surrounding this area. And to top it all the area belonged to a mimar family of Lahore. We have record of Karam uddin Mimar buying this house, and succesive generations living here.The last of this was Khan Bahadur Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Mussawar e Mashriq, Artist of the East. who again put this Mohalla on the historical map of Lahore.

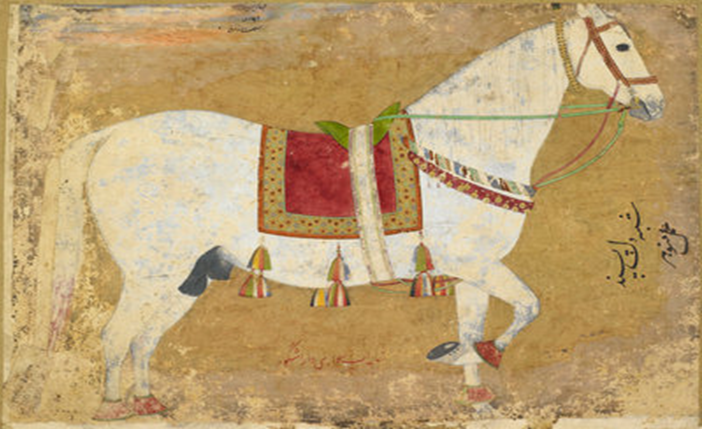

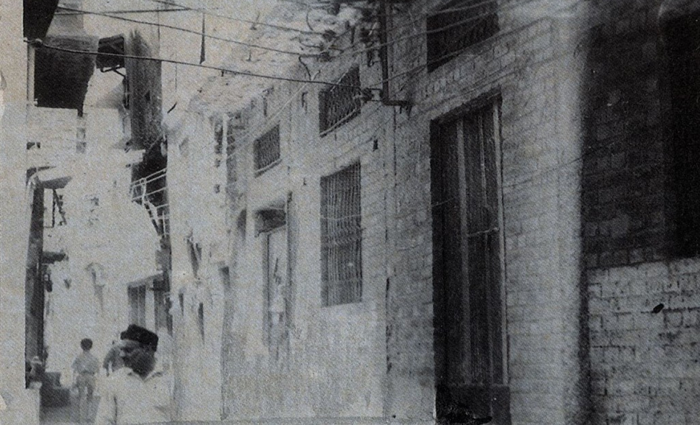

Mohalla Chabuk Sawaran

Abdullah Malik’s reference about Kocha Chabuk Sawaran:

The most fascinating part of Abdulla Malik’s autobiography, which holds little back, are his early memories of the old city of Lahore. He writes, “I was born in the last years of the second decade of the 20th century, on 20 October 1920 in Lahore’s Koocha Chabukswaran, which was located in the heart of the city. Relying on my earliest memories, I can say that all the streets around ours, and in fact our immediate neighbourhood, the area bazars, the mosques, the takiyas, the public baths, were part of Haveli Mian Khan. This Haveli was built in Emperor Shahjahan’s reign by his Prime Minister Nawab Saadullah Khan, but it was completed during the time of Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir by the Nawab’s son, Mian Khan, governor of Lahore. This grand edifice was spread over an area of several miles and it was divided into three sections: the women’s quarter, the men’s quarter which was called Rang Mahal, and the Qalai Khana, whose walls touched those of Masjid Chinyaanwali.”

Note reference to Qalai Khana.

Source:

AUGUST 30, 2014

Lahore’s Kucha Kakezian

Raza Rumi

This evocative picture of Mohalla Kakazaian was taken by tango and the story below is from Khalid Hasan entitled Abdulla

Malik’s old Lahore published in the Friday TImes Lahore.

At the age of 81, Abdulla Malik published an account of the first twenty-seven years of his life. In a brief foreword to the book, Purani Mehfilain Yaad aa Ra’hi Ain , he wrote, “I am eighty-one years old now and I can declare with pride that I have spent my entire life wedded to the same commitment, the same set of beliefs, namely the establishment one day of a socialist Pakistan. It will not come as the negation of any religion or faith, nor a revolt against God. In fact, it will be a message of love for mankind, a message that transcends all religions, faiths and creeds.”

The most fascinating part of Abdulla Malik’s autobiography, which holds little back, are his early memories of the old city of Lahore. He writes, “I was born in the last years of the second decade of the 20th century, on 20 October 1920 in Lahore’s Koocha Chabukswaran, which was located in the heart of the city. Relying on my earliest memories, I can say that all the streets around ours, and in fact our immediate neighbourhood, the area bazars, the mosques, the takiyas, the public baths, were part of Haveli Mian Khan. This Haveli was built in Emperor Shahjahan’s reign by his Prime Minister Nawab Saadullah Khan, but it was completed during the time of Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir by the Nawab’s son, Mian Khan, governor of Lahore. This grand edifice was spread over an area of several miles and it was divided into three sections: the women’s quarter, the men’s quarter which was called Rang Mahal, and the Qalai Khana, whose walls touched those of Masjid Chinyaanwali.”

After the British occupation of Punjab, the first mission school in the city was established by a clergyman named Farmson. That school came to be known far and wide as the Rang Mahal Mission School. In front of the school stood the mosque named after Muhammad Hafeez Chabukswar. Since the mosque was situated in the Rang Mahal area, it became popularly known as Masjid Rang Mahal. Koocha Chabukswaran, where Abdulla Malik was born, took its name from the Chabukswar family, who were professional horse traders and who belonged to the Pakhtun Kakezai tribe that originally migrated from Afghanistan.

Abdulla Malik writes, “It is hard to outsmart a Kakezai. The story goes that a crow once spotted a Kakezai sleeping flat on his back on a cot in his courtyard with his eyes open. The crow thinking the man was dead, decided to feast on him. Swooping down, he landed on his face. The Kakezai opened his mouth and one of the crow’s claws slipped into the Kakezai’s mouth which the man immediately closed, clenching the claw between his teeth. Realising that he was trapped, the crow thought of a stratagem. He asked the man what his caste was. The idea was that the moment he opened his mouth with an answer, it would free the crow’s claw and he would fly away. ‘Kakezai,’ the man muttered.” The crow remained trapped because you can pronounce the word Kakezai without unlocking your teeth. Anyone who does not believe it is welcome to try.

Abdulla Malik recalls that the street next to Dabbi Bazar was called Ghaggar Galli, most of whose residents were Hindu. It was called Ghaggar Galli because the loose lower garment worn by its Hindu women was called ghaggra . There were also a few families of Kashmiri Pandits who lived there and Abdullah Malik’s grandfather, to whom he was far closer than he was to his father, had the most friendly relations with them. On the occasion of the festivals of Diwali and Dusehra, the Hindu families would send their Muslim neighbours gifts of sweetmeats, a gesture that was reciprocated by the Muslims when Eid came around.

In 1925, Abdulla Malik writes, Justice Shadi Lal became the Chief Justice of the Lahore High Court. It was the same year in which Maulana Abu Muhammad Syed Deedar Ali Shah, the Khatib of Masjid Wazir Khan, declared Allama Iqbal a kafir and outside the pale of Islam. The Allama had earned the ire of the clerics because he had advised them not to interfere in the internal politics of Saudi Arabia. Maulana Suleman Nadvi declared the fatwa an edict born out of ignorance. This only shows how the mullah’s mind works. The mullahs of today are far more dangerous than the mullahs of eighty years ago because the mullahs of today are armed with deadly weapons and command suicide bombers. Abdulla Malik recalls that Lahore was plunged into turbulence when the British principal of the Mughalpura Engineering College was accused of having insulted the Prophet (PBUH). Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari spoke all night at a protest meeting held outside Modhi Gate and when it ended in the early hours of the morning, so emotionally charged had become the crowd that it started marching towards Mughalpura to settle scores with the principal. Later it turned out that the only reason this fabricated charge had been made against the Englishman was his refusal to grant admission to a number of undeserving students.

Abdulla Malik remembers a memorable visit to Lahore by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru for the annual session of the All India Congress, which was held on the banks of the Ravi. He writes, “When Nehru arrived at the Lahore railway station, he was received by milling crowds. Among those who were there to welcome Nehru, were men like Dr Saifuddin Kitchlew, Maulana Zafar Ali Khan, Abdul Qadir Kasuri, Chaudhri Afzal and Dr Satya Pal. Nehru was put on a shimmering white horse and taken in a grand procession along Circular Road and into the old city through Dehli Darwaza, Chowk Wazir Khan, Kashmiri Bazar, Sunehri Masjid, Dabbi Bazar, Bowli Bazar, and then into Anarkali via Rang Mahal and Machhi Hatta. Nehru was presented with a bag of money in Anarkali. According to another chronicler and lover of old Lahore, Pran Nevile, this bag of money – a theli – was presented by the owner of the famous Bhalla Shoe Company. Justice Shadi Lal was also seen among those out to greet Nehru. Next day when his presence was reported in the press, he issued a statement saying he had nothing to do with those who had received Nehru. The next day, the Sikh leader Baba Kharrak Singh, was taken through the streets of Lahore on an elephant flanked by dancing Sikhs waving unsheathed kirpans. That was the way things were in those days.

Abdullah Malik’s book is a moveable feast and I am unable to convey its sweep and its nostalgia in a brief column. So let me end it with another of his reminiscences. “The first film that I saw was Alam Ara (the first Indian talkie) at Regent Cinema with my father. After that I saw the drama Laila Majnun presented by Maiden Theatre Company. Majnun was played by Master Nisar and Laila by Kajjan. Some time later, the Maiden Theatre Company went into film-making and its first presentation was Laila Majnun, with Master Nisar and Kajjan in the lead roles. The movie was a sensation across India. However, after my father’s death, I lost interest in both the theatre and the movies. Much of my attention was now devoted to political and religious movements and public meetings whose political theatricality impressed me deeply.”

Abdulla Malik was a one-man movement of action and ideas. There was no one quite like him – and those who knew him would confirm that it was so.

Source:

May 30, 2008

Festival of steps

Akmal Aleemi

revisits pre-Partition Lahore, the coming of electricity, and a troubled heart with no load to shed

I went to Lahore in 1942 to attend the last rites of my grandfather, who was buried in a mausoleum he built for himself and his wife. As a spiritual leader and a prominent tabib, he was earlier allowed to be buried in his business home in Delhi Gate by an act of the municipal committee (LMC). In those days many people believed in the inevitability of death and happily prepared for it during their lifetime. The house was full of mourners eating naan and potato curry. It was well lit by electric bulbs. My brother, Mustafa, buried our grandmother in a smaller-scale ceremony in the house when she died years later.

I had traveled from my ancestral village on the left bank of River Bias about 45 miles in the east. There I would study my elementary books in the home of Baldev, our next door neighbor. In 2007, when I returned to my village as a US citizen, I looked for Baldev and found out that he had retired as a dean of the faculty of agriculture at the Punjab University at Ludhiana and was known as Dr. Baldev Singh Dhillon. Everything had changed in 60 years. We used to prepare for the school exams, as night fell, in the light of a kerosene lamp. The village had no electricity.

I realize that economic migration had quietly started. My father had followed my grandfather to Lahore. They were among many country people moving to cities for better economic prospects. That is how urbanization continued and the populations of the cities swelled. Now I read that urbanization started as early as the age of the pharaohs. People migrated from Egypt under the leadership of Moses, and that continues up to our age.

The by-gone commercial center just outside Delhi Gate included businesses run by migrants from North West Frontier Province. One of them sold kebabs freshly cooked on a large cast-iron round grill fueled by burning wood. Another would sell rice pudding made with sugarcane juice. At another location, under the roofed entrance to Wazir Khan mosque, some migrant workers sold Quraquli hats and others baked bread in a clay oven.

I was told that the walled city had 12 gates and a mori. I tried to visit and count them a number of times but in vain. The city was divided among practitioners of various trades and skills such as horse trainers, arrow shooters, bow makers, metal workers, ironsmiths, flour grinders, body healers, bird killers and house cleaners. Professionals ground wheat with stone wheels and extracted oil from seeds in traditional expellers rotated by blind-folded bullocks in the city neighborhoods.

The Lahore Fort had already been occupied by colonial forces and the apartment above Delhi Gate was in possession of their subservient police. I remember its gigantic antique doors but they were always open. City gates are built to afford peace to dwellers. Aren’t they? I took many walking tours through the walled city. There were havelis of Punjabi landowners and grantees but in decay. A man sold intoxicating bhang drink in front of one of these. The store displayed an apartheid cup outside, exclusively, for “Christian brothers”.

It has been a great era. I saw the advent of electricity, planes flying in the skies during World War II, the explosion of nuclear bombs in distant cities, rationing, the end of the colonialism and the beginning of a cold war, then the end of that cold war and the beginning of neo-colonialism, a heart transplant, a landing on the moon, IBMs, natural gas, video players, television, digital recorders, computers, the internet, terrorism in the name of religion, globalization, stealth bombers and drones...

Pre-partition Lahore was fascinating. For the first time I saw incandescent bulbs burning in the four-storey home I would grow up in. In the evening, shops in Delhi Gate and Kashmiri Bazar glittered with electric lights. I visited the wartime exhibition in Minto (Iqbal) Park. I climbed on and played with Kim’s gun on The Mall. I bought a ticket to enter the Lahore Museum. I purchased halwa and kulcha from an overweight vender who would roam the area carrying his merchandise on his head. Before making a transaction he would bury the kulcha in the hot heap of halwa to make it more palatable.

When I was compering a Lahore Television show called ‘Ham Log’ (it was produced by Naseer Malki), I asked the elderly guest from Kucha Chabuk Swaran if he remembered the coming of electricity to the city. He said he did. “The night Gohar Jan Kalkatewali sang in the courtyard of the Mela Ram Mills, the first electric bulb was lighted and it surprised everyone present.”

A few years back when I fainted in the halls of the Grand Mosque and was carried to Al-Noor hospital In Makkah I realized that even a human body needs electricity to sustain it. After a Saudi surgeon had implanted a pace maker in my chest, the attending nurse from Gwalmandi consoled me with her words: ‘Uncle, don’t you worry. We have put a tiny powerhouse in your body. It will provide electricity to your heart as required. No load shedding will be needed.’

A stroll through Anarkali bazaar was thrilling. The sight of stores full of merchandise was awesome. I read a business sign as Beast Watch Company. I knew the meaning of beast. I would wonder why the watch seller would associate his company with a wild animal. Soon I realized that the business sign was in Urdu and the businessman meant “Best” and not beast. Also, I remember a shop which sold gramophone machines brand named His Master’s Voice and plastic discs. Inside, it displayed portraits of singers like K.L. Sehgal, Master Madan, Kannan Bala, Khurshid Bano, Surinder Kaur, Sureyya and Baby Noor Jahan.

I watched my first movie in Lahore. My father’s faith would not allow him to sit in a cinema house, but he did not want to deprive me of the spectacle of the bioscope. So he took me to a theater outside Bhatti Gate, purchased my ticket and dumped me inside for three hours. The film called ‘Pukar’ dealt with justice as administered by Emperor Jehangir. I remember the romantic scene in which the monarch (Chander Mohan) asks his beloved Noor Jahan (Fairy-face Nasim) how his favourite pigeon would fly out of her custody, and she innocently demonstrates by releasing the second bird from her clutches.

Before I would take a train back to my village, I watched a unique gathering that represented the confluence of rural and urban life. They called it Qadman-da-mela (festival of steps). The annual country fair was held outside Delhi Gate. Purveyors displayed their merchandise over pieces of cloth spread on the dirty ground. They sold clay and wood toys, the bark of a tree that would provide oral hygiene and paint women’s lips, colorfully sweetened balls of shaved ice and kiln-baked cooking pots. Clay toys, dear to me as a country boy, included small whistles and horses. I was attracted to them but could not buy any item because I did not carry any money. There I learned that the fair had arrived from Yakki Gate and would move to Mochi Gate after that day. It will keep moving and be held outside each of the city gates. The event will disperse after completing the circle around the walled city. That is why they called it the festival of steps.

Source:

http://www.thefridaytimes.com/27052011/page24.shtml

Send email to nazeerkahut@punjabics.com with questions, comment or suggestions

Punjabics is a literary, non-profit and non-Political, non-affiliated organization

Punjabics.com @ Copyright 2008 - 2018 Punjabics.Com All Rights Reserved

Website Design & SEO by Webpagetime.com