|

150 odd years

Sarwat Ali

Rajmohan Gandhi argues that the Punjabis themselves should devise solutions to Punjab, as outsiders have hammered out solutions that resulted in tragedy

The relationship between India and Pakistan fraught with mistrust, suspicion and misgivings has also at times broken out into open hostility. For many, this state of affairs is no longer tenable because the world has moved on, by engaging itself economically and politically, while the progress of this area has been stultified by the bitter antagonism between these two neighbouring states.

Many believe that the potential of the region cannot be realised without the two putting their past behind and looking forward for a better future.

The land is vast and has a growing population, mainly comprising the youth. The size of the middleclass is bigger than even the total population of many a country and it is tragic that with so much to offer, the full potential has somehow got lost somewhere.

It is about time that big steps are taken for the region to take charge of its future and release it from being held hostage by its past.

The foremost historians and political analysts of our times — Rajmohan Gandhi is of the same opinion but is also very mindful of the divisions that exist; the wounds have run deeper than what many had believed in the beginning. These incisions often begin to bleed again and for him the only way to come to terms with the situation is to face the reality of the land and its people. Seeking some kind of a patch up can be possible by taking this route.

Rajmohan Gandhi took into account the period which was not very good for the Punjabis — the post-Aurangzeb era to the division and partition into two independent states. He has held that by recounting history and its ups and downs we would be able to come to terms and be more appreciative of the problems that just do not seem to go away.

The Punjabi’s virtues of staying clear of clashes with the rulers, recognising the wind, picking the winner, self-preservation and assisting the endangered were evident through the period covered in the book.

He has wondered, though, as to why Punjab has always been ruled by outsiders. The first Punjabi to have ruled this land for centuries was a Muslim Adina Beg in 1758 for a transitory spell in the name of the Maratha Confederacy. The Punjabis should devise solutions to Punjab as the outsiders in the recent past, the Empire, Indian National Congress, Gandhi, Nehru or Jinnah, hammered out solutions that resulted in huge tragedy.

The Punjabi’s virtues of staying clear of clashes with the rulers, recognising the wind, picking the winner, self-preservation and assisting the endangered were evident through the period covered in the book. However, these assets did not suffice against the passions unleashed in Punjab even as they had not sufficed against earlier eruptions. At more than one critical stage a bold and local leadership that stood up to extreme drives has been Punjab’s unmet need.

Rajmohan Gandhi was born in Delhi in 1935 and grew up with a mild anti-Punjabi prejudice. At that time, it was not a Punjabi city as it was to become after 1947. Though it had been part of the Punjab province from 1848 to 1911 when it again became the capital of India, the Punjabis were not the dominant community.

Delhi was a non-Punjabi city. Actually Punjab had been the base for the empires crushing the great rebellion in Delhi, an exercise in which the Sikhs and Muslims Dogras and Gurkhas enlisted fully.

When he grew up Gandhi realised, principally through his teachers that the Punjabis were wonderfully gifted and friendly who loved the place they came from. Gradually, he felt for Punjab and Punjabiat. This is the history of the Punjab from the death of Aurangzeb to the Colonial Raj. These 150 odd years were not easy for Punjab because there was political instability, invasions and raids and finally the holocaust of the partition in 1947, when this area bore the brunt of the rioting and bloodletting which can be considered the consequence of the largest migration of people in history.

The boundaries of Punjab are as if set by geography. The natural boundaries of Punjab are the Indus River to the west, Himalayas to the north, in the east by Jamuna, on the south and south west and the Thar Desert, Aravalli Hills that circumvent Delhi and the land in the middle consists of a number of Doabs — the land between rivers. In 1840, the British contributed to Punjabiat by abolishing duties on goods or produce travelling in the region.

The long-lasting trauma, or rather the need among Indians and Pakistanis to get out of it, is probably the strongest impulse even if mostly in the subconscious. Behind this inquiry, he was venturing under a half-recognised pull to assist, no matter how poorly, healing of the wounds. While most accept that historically there is no reconciliation without establishing the truth, clinically it is an impossible exercise; yet it may be possible to strive for a balance in historical perspective by studying a variety of conflicting accounts.

From the map four separate pieces which may grow into five. Punjabiat faces gigantic foes. At the lower and perhaps deeper level the Punjab psyche contains fibre memories of a longing for a fresh start. Pragmatism more than anything else may produce a generation to find a climate of goodwill rather than that of hostility. What can brighten the prospects are enlarged trade, unexpected statesmanship from Delhi/Islamabad, or Chandigarh/Lahore, the unqualified rejection of extremism, and coercion whether in politics or religion. Individuals too can revitalise Punjabiat, healing and renewal can also come from the ordinary men and women by thinking of their children and grandchildren. For tomorrow’s sake they should learn from yesterday.

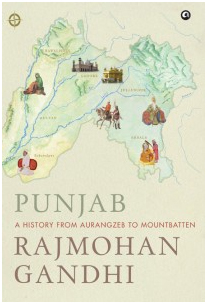

(Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten is available at Liberty Books)

Punjab

A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten

Author: Rajmohan Gandhi

Publisher: Aleph Book Company, Delhi, 2013

Pages: 432

Price: PKR1595

Curtsey:The News: January 12, 2014

|