|

Book launch

A milestone in Punjab research

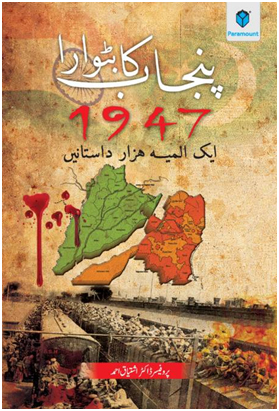

Punjab Ka Batwara: Aik Almyia Hazaar Dastaaney Translated by: Vaseem Butt; Author: Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed Publisher: Karachi, Paramount Books; Pgs: 558; Price: Rs 1,295

By Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed

With the publication of this Urdu translation of my book, The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First-Person Accounts, a milestone has been achieved not only by me as a researcher and an academic but also in terms of the research on the history and politics of the Punjab partition of 1947. I know of no other people in the world who are so grossly uninformed on either side of the Punjab border about their shared past. On both sides, nationalist narratives highlight the crimes and injustices of the other side and more or less absolve their own. For the first time now, the truth is available far beyond the narrow English-speaking Pakistani elite. Since most Pakistanis, including of course Punjabis, receive education in the Urdu language, they can now read for themselves and learn about the events that transpired in undivided Punjab until the Radcliffe Award laid down the international border in Punjab between what became Pakistani west Punjab and Indian east Punjab, and also of what happened when power was transferred to the two Punjabs.

They can appreciate for themselves the enormity of the calamity that struck hapless men, women and children who were dehumanised and became legitimate targets as Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. Out of Punjab’s total population, including that of British-administered Punjab and the Punjab princely states, of almost 34 million, 10 million had to flee hearth and home to save their lives. That meant that nearly 30 percent of Punjab’s population was forced into flight. At the end of the day, the first case of massive ethnic cleansing was achieved because virtually no Hindu and Sikh was left in Pakistani Punjab and no Muslim in Indian Punjab. Anywhere between 500,000 to 800,000 Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, men, women, the old and children were killed, and 90,000 women were abducted, oftentimes raped.

It goes to the credit of Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander and a host of other great writers who have, in their Urdu fiction, captured some of the most shattering aspects of the Punjab partition. Now, for the first time, after labouring for nearly 12 years, some 230 accounts of what hell Punjabis went through in 1947 are presented. Additionally, British secret reports and newspaper accounts are examined in detail.

One of the reasons for undertaking the Urdu translation has been to facilitate further research on Punjab. We have ensured that an identical reference system is maintained. Young Pakistani researchers can learn the methodology that was employed as well as the theoretical framework devised to make sense of the empirical material that is examined and analysed. Unlike historians who focus on individuals, this book sheds light on the thick cultural and structural objective reality that both defined and circumscribed the ability of individuals and groups to act in such disturbed circumstances. In other words, the orientation of the book is definitely towards social science and not just descriptive history. The Punjab partition is shown as a process constituted by actions and reactions, and intended and unintended consequences. Thus, high politics are connected to provincial politics and their consequences traced deep into the towns, mohallas (neighbourhoods) and villages of Punjab.

In a special section called Izhar-e-Tashakur (thanks), which is actually a second preface for the Urdu edition, I have included three more stories. One is about the stranger-than-fiction story of Harbhajan Kaur and her five Pakistani Muslim children, who were reunited after some of us made special efforts to facilitate this task. The second story is about my meeting with Mr Lalit Jain in Delhi in 2013. He tells us a fascinating story of pre-partition friendship between his father and the father of my dear friend in Stockholm, Riaz Ahmed Cheema. Both had studied at Law College, Lahore, and served in the judicial branch of the Provincial Civil Services (PCS) cadre. He also narrated the heart-wrenching story of a West Punjabi Hindu family that shifted to Karnal. The addition of these two stories underscores that the Punjab partition inflicted unbearable pain and sorrow, and yet there were those who held on to their humanity and took great risks to reaffirm it.

A philosophical question does come to mind though in regards to whether the wounds of the past should be reopened or should be left to heal on their own. My conviction is that these wounds have been open all along and people have been suffering in silence. Perhaps in another 10-15 years the generation that directly experienced the trauma will be gone and thus the wounds will naturally cease to matter. I doubt that very much. I think, instead, one-sided narratives will get entrenched in official and communal histories and consequently the coming generations of Punjabis will be brainwashed to continue the victimhood syndrome, and blame the other side for the excesses of the past.

With this book now available in Urdu in Pakistani Punjab, at least on this side, an antidote to one-sided narratives is now available. The great news is that a Gurmukhi translation has been completed and the Hindi translation will soon start. As a Punjabi who grew up battling with the greatest tragedy that befell my people, my life’s mission will then be complete.

Curtsey:Daily Times: May 12, 2015

|