The past few months have been a struggle for those fighting for digital rights in Pakistan. While they are a small minority in the grand pool of activists in the country, they have had their hands full with the new proposed cybercrime bill (#PECB15) determinedly being pushed forward by the concerned officials.

Currently, the bill has been passed by the National Assembly Standing Committee on IT and seems to be moving swiftly along. A little background might help to understand why the bill is being pushed forward so quickly, and why this proposed bill should be important to us as citizens.

In December 2014, a not-for-profit digital advocacy group I work for, Bolo Bhi, filed a petition in the Islamabad High Court to challenge the legality of the Inter-Ministerial Committee for the Evaluation of Websites (IMCEW).

Bolo Bhi had found, after filing in the Right to Information requests, that the IMCEW had no legal standing and yet, were passing directives to block content online, even if they were not of a blasphemous or pornographic nature.

The IMCEW was disbanded in March, after it became obvious that the courts were convinced that the body was unconstitutional. However, as expected, our Prime Minister stated that the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) would now have the authority to manage content online, without paying any attention to the lack of transparency and accountability in the current process.

The PTA was created by act of Parliament, which means the powers vested in the PTA are to be granted through law, not by a statement made by the prime minister.

And that is all the more reason why it is so critical to know what this new proposed law holds for us.

The addition of Section 31 of the Proposed Cybercrime Bill gives PTA:“Power to issue directions for removal or blocking of access of any intelligence through any information system…if it considers it necessary in the interest of the glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defence of Pakistan or any part thereof, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, commission of or incitement to an offence.”

This has created an excessively broad scope to justify blocking material online.

For example, criticism of The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, or the United States of America, could fall under “friendly relations with foreign states”. Thus any newspaper, online media, or material on social media in regards to such criticism can and most likely will be blocked. There will be no need for a direct order from the Supreme Court, or an evaluation of the material, it will just disappear off the Internet.

We have already seen that happen with the disappearance of Fahd Hussain'scolumn on the UAE minister's statement; we may have power to dispute such blocking today, but if this bill is passed, there will be very little we would be able to do.

I could come up myriad examples of what all can be blocked/banned by twisting around the aforementioned "justifications”; but we are all already well aware of the blocks and bans Pakistan is known to impose under the garb of “national security” or “terrorism”.

To take away our right to fight the constitutionality of the banning and blocking of websites, the government wants to pass the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2015. This will allow the PTA to block anything, on ANY information system (which could possibly include your phones, your televisions, even your Xbox and PlayStation, because they have the ability to connect to the Internet), and there will be very little you can do about it.

But besides taking away our ability to challenge, this bill has found its way to infringe upon our freedom of expression and opinions.

Article 19 of the Pakistan Constitution says

“Freedom of speech, etc – Every citizen shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression, and there shall be freedom of the press, subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam or the integrity, security or defence of Pakistan or any part thereof, friendly relations with Foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, 1 [commission of] or incitement to an offence.”It would be good to mention here that the website of a well-known Human Rights Group, Article19.org, is blocked on a certain ISP here in Pakistan, ironically. When asked about it, they said: “The PTA directed them to do so”. This was on April 15, 2015, even before the bill had been passed.

How does a website on the freedom of speech upset the “glory of Islam” or “security, integrity or defence” or effect Pakistan negatively in any way? It doesn’t; it just irks the government, that's all.

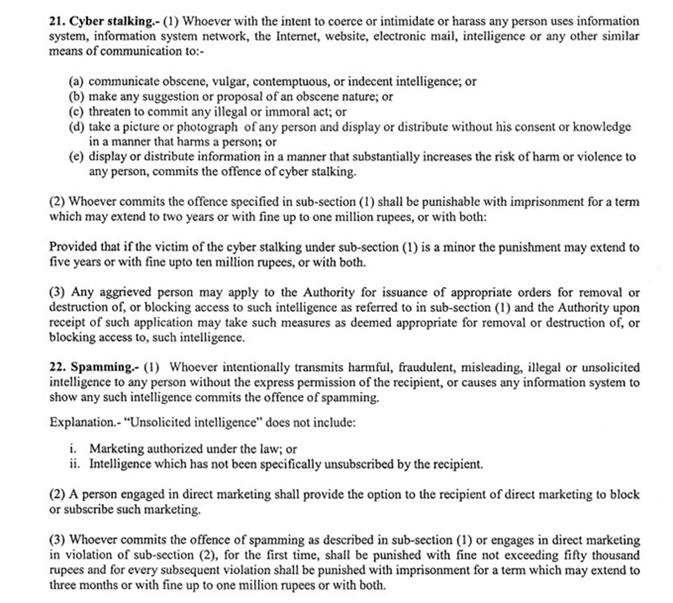

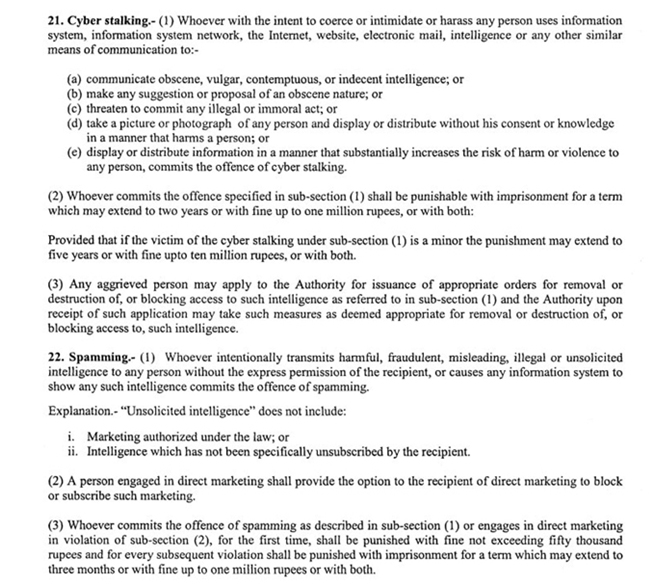

This proposed bill will do just the same; it will suppress our ability to express our opinion, to write freely, to create memes, or cartoons, especially ones that are political in nature or even upload pictures of people without asking their permission.

In fact, you will not even be able to send out a mass text, e-mail or any such thing without explicit consent of the receiver. Just read the most recent draft of the draconian cybercrime bill. In other parts of the world, spamming is dealt with differently, and penalties are only imposed if spamming is done for commercial purposes. Not so here.

In the event that you get charged with a crime under this bill, a warrant will either exist as a formality or not at all. The wordings of the act regarding the warrants is so vague and open-ended, that it seems it was just added to make it sound like defendants were being given the right to due process.

The Law mandates ISPs to retain your data for 90 days, and thus, can be forced to give up your browser history and/or other information that we once believed to be private. In fact, if you’re charged under this law, you may be forced to give investigating officials open access to all your data, online or on your computer/information devices.

In the absence of a Data Protection Law, the introduction of a loosely worded cybercrime law would be devastating for civil liberties and businesses in the country.

These provisions in the proposed bill are an infringement on the right to free speech; the right to expression; the right to free media; the protection from undue searches and seizures; the right to NOT incriminate oneself; and the right to conduct business. From how it looks, even media outlets would be severely persecuted under this law.The draftspersons of this bill seem to have forgotten that there are some inalienable rights given to a Pakistani citizen and that no law violating them can be passed. The fact that the law has moved forward on the floor of the assembly is incredibly worrying.

It seems as though lawmakers have no clue that this law will be in violation of our constitutional rights. It is important that we as citizens identify and understand the problems with this bill, and not stand by while it is in the process of being enacted.

We need to break the silence.

Madiha Latif is a graduate from Rider University, New Jersey in Political Science, Economics and Global Studies. She has been working with Bolo Bhi since 2013. She is currently pursuing a Law Degree and hopes to complete her PhD one day.

She tweets @madiha_latif.

Courtsey:DAWN.COM:

http://www.dawn.com/news/1176538/why-pakistans-cybercrime-bill-is-a-dangerous-farce

Pakistan got its first constitution, nine years after independence, on March 23, 1956. This constitution guaranteed the right to freedom of expression under Article 8. The freedom of press was not mentioned here. This constitution was based on the Government of India Act of 1935 and was abrogated by the military regime of Field Marshal Ayub Khan in 1958.

The new constitution, promulgated in 1962, guaranteed the right to freedom of expression under Article 6, but it too failed to provide for the right to freedom of press. The constitution of 1962 was soon abrogated by the military regime of General Yahya Khan and after his regime fell, the democratically elected government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto set about formulating yet another constitution for Pakistan — a task which was completed in 1973. It was a ‘consensus Constitution’ — all parties concerned seemed satisfied. The Constitution of 1973 guaranteed the right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19 and it also guaranteed the right to freedom of press.

The Constitution guaranteed that all citizens of Pakistan shall be free to express opinions and ideas, without being punished for doing so. This means that citizens may speak their mind, put their ideas or opinions in writing, get them published, post them over the internet, or express as they feel in any manner possible — this includes various art forms and any other perceptible statement. This includes the right to seek, receive and impart information, ideas or opinions, in any form which may be available.

Pakistan has had a chequered history of freedom of press. Pakistan enjoyed a very brief period during which there was complete freedom of press and that ended with the death of Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Soon after, newspapers started getting banned and their editors were hauled off to prisons. Successive governments continued to arm-twist the press. A number of laws were enacted to restrict freedom of the press and to browbeat journalists into keeping the truth from the public.

It should be noted that countries around the world impose some reasonable restrictions on the freedom of speech. Absolute freedom of speech is bound to be misused by certain elements and have negative effects on society. Nothing should be expressed in a way, which may defame someone or may offend the notions of morality of a person, or may incite someone to an act of lawlessness.

Curtsey:The Express Tribune, June 19th, 2013.

Advocate Asma Jahangir was the keynote speaker at the 27th convocation of the university. PHOTO: LUMS FACEBOOK PAGE

LAHORE:

Former Supreme Court Bar Association president Asma Jahangir on Wednesday called upon the graduating batch of students at the Lahore University of Management Sciences to work towards promotion of freedom of speech and religion in the country.

She was delivering the keynote address at the 27th convocation ceremony at the university.

Jahangir said the graduates should uphold principles of freedom of speech and religion, respect for human rights and tolerance towards others’ beliefs and practices regardless of their career choices.s

Jahangir said those proceeding to employment should bear in mind that they were graduating from one of the most prestigious institution in the country. “Your opinion will carry a lot of influence. You can change the world around you with your actions,” she said. Jahangir advised students to work in collaboration with people who share their principles rather than in isolation. “Build institutions to promote sustainable change in the society,” she said.

Addressing females in the graduating batch, she said they should not feel any shame in standing up for their rights.

Jahangir concluded her speech by congratulating the graduates and thanking the LUMS administration for inviting her to the event.

Earlier, Vice Chancellor Syed Sohail Naqvi urged the graduates to be grateful to their parents and teachers who had supported and guided them throughout their academic career. “I am certain that your graduation would not have been possible without the support and guidance of your parents and teachers,” he said.

The convocation ceremonies had started on Tuesday night with a graduate dinner. The winners of the National Management Foundation (NMF) and corporate medals and those placed on the dean’s honour list were recognised at the event.

The ceremony on Wednesday started with a procession of the graduating batch that ended at the convocation venue. Degrees were awarded to 869 students from the four schools: Suleman Dawood School of Business (SDSB), Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani School of Humanities and Social Sciences (MGSHSS), Syed Babar Ali School of Science and Engineering (SBASSE) and Shaikh Ahmad Hassan School of Law (SAHSOL).

“People demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought, which they seldom use,” wrote Kierkegaard, realising that there are very few men who can afford to think, and a whole lot of humanity wanting to speak. Speech, admittedly, comes more trippingly on the tongue than losing one’s head on a hard issue. There are men who can effectively speak and yet prefer to stay silent. It is then said that their reticence speaks more eloquently than their speech. Then there are people who thrive on their’s or people’s right to speak, about whom Khushwant Singh has quoted Philip Howard’s cheeky remarks, “Journalists are like dogs. When one barks, the whole pack takes up the howl and, for a week or two, the world seems full of nothing but sentencing for rape, say. Then the subject becomes boring and the pack moves on.” However, Khushwant Singh was wise enough to take up cudgels on behalf of his fraternity to debunk the politician’s habit of journalist bashing by terming the politicians crooked as a dog’s hind legs.

Not only has freedom of speech added colour and zest to our lives, and made it more democratic and accountable, it has also left deep imprints on the course of history. It has been said that the history of civilisations is the history of conscientious objections, which radically changed the course of events. It has often wrought miracles in the past and, in most cases, changed the course of history. Marc Antony, through his famous oration on the funeral of Julius Caesar, unveiled the murderous plot of Brutus against Caesar and turned the tables on the conspirators by the sheer force of his speech. Martin Luther, the founder of the Protestant Reformation, by his courageous oratory against Papal corruption brought about a revolution that led to a series of wars in Europe and changed the course of history.

In any case, freedom of speech is a serious matter and, in the words of George Washington, “If freedom of speech is taken away, then dumb and silent we may be led, like sheep to the slaughter.” John Stuart Mill, the greatest advocate of this freedom, was led to say, “There ought to exist the fullest liberty of professing and discussing, as a matter of ethical conviction, any doctrine, however immoral it may be considered.”

Man began to assert his right to speak since time immemorial. Socrates, in 399 BC, said to the jury that told him he would be freed on condition to never speak his mind that he would sooner “obey the Gods rather than them”. Protection of speech was first introduced when the Magna Carta was signed in 1215. In 1689, the English Bill of Rights granted freedom of speech in Parliament and the French established the protection of speech in their Declaration of the Rights of Man in 1789. In 1948, the UN recognised free speech as a human right in article 19 of the International Declaration of Human Rights.

The problem with the democratic governments of today is how to allow freedom of speech to their citizens while simultaneously ensuring peace, order and tranquillity. Experience has shown that there is no such thing as absolute or unqualified freedom of speech because an unbridled use of this freedom would surely bring chaos and disorder. Hence, even in the most liberal democracies of the world, severe limitations have been imposed on the freedom of speech. The US constitution, considered to be the most liberal document, through its first amendment has restrained Congress from making any law “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble”, which has been interpreted by the Supreme Court over a long period of time to include nearly all the restrictions that have been specifically mentioned in the constitution of Pakistan. Thus, in the US, freedom of speech is restricted by factors that include speech involving incitement, false statement of fact, obscenity, child pornography, threats, and speech owned by others.

Besides these, freedom of speech also does not allow slander, libel, sedition, copyright infringement and revelation of classified knowledge. Viewed against these restrictions on US society, the constitution of Pakistan, under Article 19, explicitly lays down: “Every citizen shall have the right to freedom of speech and freedom of press, subject to any reasonable restrictions imposed by law in the interest of the glory of Islam, or the integrity, security and defence of Pakistan or any part thereof, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, commission or incitement to an offence.” In the Indian constitution too, under Articles 19, 20, 21 and 22, the same restrictions have been placed on freedom of speech with the only difference being that in India only those reasonable restrictions are considered valid that are imposed by a duly enacted law and not by an executive action. Thus, the entire gamut of law on the freedom of speech leads one to conclude, “Your freedom to swing your fists ends where my nose starts.”

The recent murderous attack in Karachi on Mr Hamid Mir has opened a debate on the freedom of speech and propriety in this case of display of the picture of the head of the premier intelligence agency of Pakistan for nearly eight hours on its media channel in a way intending to scandalise this important organ of the state and without concrete evidence, presenting mere suspicion as fact, making the public believe as if the attack had been launched by the agency’s head. The incident has a legal as well as an executive angle. On the legal side, it leads to the offence of attempt to murder, which, after police investigation, will be tried and decided by the court of competent jurisdiction, while on the executive side due to the way it has been flashed on the electronic media, the matter falls under the purview of the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA).

After the Sikander incident in the Blue Area of Islamabad in August 2013, a commission to formulate a code of conduct for the electronic media was constituted, which, it has been reported, has submitted its recommendations to the respective Standing Committee of Parliament without further progress. The case relating to the attack on Hamid Mir hinges on the complainant’s suspicion of the intelligence agency, which he implicates on the basis of his pre-announced doubt. Doubt or suspicion, however strong, always fall short of the force of hard evidence or even secondary evidence and, therefore, conviction on that basis alone cannot stand.

However, the fact of scandalising the incident and bringing the agency and its head into dispute on the basis of suspicion alone has grave consequences for the media house. The law relating to libel and slander as enunciated under Article 19 of Pakistan’s constitution (and even the constitutions of other countries like the US, UK or India) do not permit presenting or publishing a suspicion as fact, nor does the code of ethics of journalistic bodies of Pakistan like the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) or Council of Pakistan Newspaper Editors (CPNE) allow the publication of unverified matters as facts.

Curtsey:Daily Times, May 05, 2014

AFP

LAHORE: After issuance of a direct life threat to senior journalist Imtiaz Alam, journalist community, political parties and civil society organisations held a protest demonstration on Sunday.

Members of the Lahore Press Club (LPC), Punjab Union of Journalists (PUJ), Human Right Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), South Asia Free Media Association (SAFMA), South Asia Partnership-Pakistan Chapter (SAP-PK), Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), and Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) participated in the demonstration to condemn the issuance of threats to journalists.

Speaking on the occasion, senior journalists Hussain Naqi, Najam Sethi, Kamran Shafi, Khalid Chaudhry, Ejaz Haider, Arshad Insari, Mian Shahbaz, Waseem Farooq, and Fawad Chaudhry, of the PPP, and Riaz Durrani, of the JUI-F, expressed their resolve to continue their struggle to ensure freedom of expression and against anti-progressive elements and terrorists in society.

Urging the Punjab government to provide adequate security to journalists, Naqi also demanded that the government must perform its responsibility towards ensuring freedom of expression and curb the Punjabi Taliban and stop them from threatening media persons.

He also urged the All Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS) and the Council of Pakistan Newspapers Editors (CPNE) to hold direct talks with the Taliban to stop them from issuing life threats to members of the press corps. He also suggested media houses to jointly hold a boycott of all terrorist organisations.

He further suggested the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ), the PUJ and other media organisations to call for holding a countrywide movement against terrorism in order to secure the lives of their members and also to raise their voice at international level.

Regretting over thin participation of journalists in the demonstration, he also suggested employees of media houses and other entities to become united on a single platform after setting their differences aside for the cause of ensuing freedom of expression and independence of the press.

Sethi said that Pakistan is more dangerous country then Afghanistan. Unfortunately, he said, neither the government nor the media houses were giving protection to journalists and this is enhancing insecurity among workers. He urged the media houses to take solid measures to protect their workers. The workers should also enhance pressure on their employers to give them protection.

PPP delegate Fawad Chaudhry strongly condemned the issuance of life threats to Imtiaz Alam by the Taliban and said that his party would continue its struggle for a progressive and liberal Pakistan. He said that PPP Patron-in-Chief Bilawal Bhutto Zardari had also condemned the issuance of life threats.

JUI-F representative Raiz Durrani also condemned the issuance of life threats to journalists and said that his party would also continue to oppose terrorism at every level.

LPC President Arshad Insari said that he had received at least six threatening letters from the Taliban. He vowed that his community would continue its struggle for a progressive society. PUJ President Waseem Farooq said that terrorists could not suppress the voices of the media through issuing such threats.

Shafi and Haider urged journalists to become united in order to protect and preserve the freedom of expression.

Some prominent figures of media, political, and civil society organisations like Prof Aziz, Mohammad Tehseen, Anjum Rasheed, Mehmal Sarfaraz, Azhar Siddique, Sabir Shah, Ayaz Khan, Latif Chaudhry, Khalid Qayyum, Shafiq Awan, Riaz Bhatti, Shahzad Malik, Yasin Mughal, Salahuddin Butt, Tahir Bukhari, Amrez Khan, Zia Tanoli, Shahbaz Anwar, Asim Shahzad, Abdul Qadir Madni, Arshad Bhatti, Khalid Farooq, Saeed Akhtar, Waleed Ahmad, Atta Mohammad, Fazlur Rehman Butt, and Zafar Malik also participated in the demonstration.

Curtsey:Daily Times, April 07, 2014

Freedom of speech is a core liberal human right, one that western democracies put on the highest pedestal. Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) states that “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” The chief theorist of freedom of speech was the 19th century British liberal thinker John Stuart Mill. Mill argued that the only way society can progress is by letting human beings express their views and opinions freely. If everyone enjoys such a right then the listeners or readers will be able to figure out which standpoint is rational and cogent and which is flawed and unconvincing.

Mill put a very high premium on human intelligence and rationality. He recognised individuals as intelligent, autonomous agents capable of making correct choices if they are given several alternatives. Consequently, Mill asserted, it does not matter if bad or wrong ideas are expressed because only when such ideas exist can human beings make out what is right and what is wrong. He argued that the west transformed into the leading civilisation of the world because freedom of speech underpinned the freedom of enquiry, which made possible scientific research and the inventions and discoveries such research produced.

Did Mill then support unrestricted right to free speech and expression? The answer is no. He made a distinction between the written word, which he believed required some level of serious reflection and unbridled verbal speech, which could result in the abuse of freedom of speech and cause social unrest and upheaval. An example he identified was working class agitators who could rouse vile passions among the workers through demagogy and thus instigate them to violent action against factory owners. Such rash use of freedom of speech he wanted to restrict and prohibit.

Additionally, he introduced the harm principle to regulate liberty. Action and speech that resulted in harm to others constituted an offence that should be punished, he asserted. It is not clear if he meant physical harm only or harm in the larger sense of the word, which could include psychological torment as well. Therefore, one can say that Mill’s defence of freedom of speech and expression was not without qualifications and reservations, and some amount of vagueness. One can also argue that he privileged freedom of speech that appealed to the educated middle classes but not that of workers; he seemed to be against the freedom of the working class to challenge the bad conditions they labored under in 19th century England.

In any case, nowhere in the west is freedom of speech without regulations. Slander (verbal character assassination) and libel (character assassination in written form) are offences against which people can move the court for redress. However, slander and libel cases can be admitted by courts only if living human beings are adversely affected: their reputation is tarnished and their economic interests thus suffer. However, individuals dead and gone, including religious icons and founders, are not protected by slander and libel laws.

The US has probably the most liberal laws on freedom of speech and even infamous, extreme right wing organisations such as the unabashedly racist Ku Klux Klan are free to publish their point of view as long as they do not incite violence against non-whites, Jews and other minorities. On the whole, in western societies, preaching hatred against ethnic and religious minorities is a criminal offence. So, preaching hatred of Muslims would be treated as a criminal offence in western democracies and the culprits put on trial and punished if found guilty.

Having said this, it is important to note that, in the west, religious freedom is guaranteed. It is upon such a basis that mosques have been constructed in western cities and localities where sizable Muslim immigrant populations are found. No doubt, considerable resistance was given by native populations who perceived the growing Muslim presence threatening but permission was granted and mosques are being built in the west.

However, not only is freedom of religion guaranteed in the west but also freedom from religion. Nobody is obliged to believe in a religion and therefore sceptics, agnostics and atheists are free to follow their own moral codes. As long as people obey the law and pay taxes they can lead their lives as freely as they want. There are people who write against religions and satirical magazines also exist in many western democracies. Their publications do offend, in some cases deeply, the feelings and sentiments of believers. Their standpoint is that religions divide humanity, uphold gender inequality, oppose gay rights and historically have been responsible for wars, minority persecutions, including ethnic cleansing and genocide, and other excesses. The general understanding is that only when philosophers and scientists were liberated from the tyranny of theology and orthodoxy could knowledge unfettered by dogma grow by leaps and bounds and the west liberalise, democratise and pluralise.

Such an interpretation is a compelling one but one cannot deny that, under the garb of freedom of speech, some troublemakers deliberately abuse such freedoms to conceal their prejudices against Muslims and other groups. The same people would be very wary hurting Jewish sensibilities because the Jews are no longer perceived as a dangerous race. There is no denying that some forms of Muslim behaviour in the west are primitive and aggressive, and that such behaviour plays into the hands of anti-Muslim parties and movements, frightening ordinary people.

However, many westerners do retain faith in Christianity or at least value their Christian identity. I have lived in perhaps the most secularised of western societies, Sweden, for more than 40 years and even there some people are pious believers. I remember once, during the Christmas holidays, an old Swedish lady protested in a letter to the editor of a leading newspaper that a television channel had shown some programme casting Jesus in a bad light: as gay. So, it is not surprising that when the cartoons of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) depict him in ways and forms many Muslims find scandalous, they are deeply offended

Curtsey:Daily Times, February 10, 2015

Banning just the cartoons of the Prophet (PBUH) as an exception to the general praxis would be a contradiction difficult to justify

Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed

Last week I argued that freedom of speech and opinion is guaranteed in the west but laws do exist to penalize the character assassination of living human beings. Those dead and gone, even founders of religions, are not covered by these laws. The reason for such a distinction is that harm can only be done to someone alive. A deceased historical figure cannot personally be harmed by adverse portrayal in written or artistic form such as a cartoon. This distinction is of course a product of modern times because, in the past, blasphemy laws existed to punish those guilty of disrespect to the official religious dogma upheld by the state.

Some readers pointed out that Holocaust denial constitutes a criminal offence in the west. How does such a standpoint make sense if only slander and libel cases affecting the rights of living individuals are punishable offences? The situation is somewhat like this: Holocaust denial is criminalised by some western states but not all. Currently, the following European countries criminalise it: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Spain and Israel. Germany and Austria, from where the Nazi ideology originated and the Holocaust took place, take these laws very seriously and prosecute holocaust deniers in a firm way. Others, like Lithuania and Romania, despite upholding such laws, enforce them sporadically. Then there are those countries that put a higher value on free speech and do not crimialise Holocaust denial. These include the UK, US, Ireland and the Scandinavian states.

Those who favour criminalising Holocaust denial mean that to deny that six million Jews and other ethnic minorities perished during the holocaust is to condone the most well-documented mass murder in history. If tolerated it would encourage apathy and disregard for crimes against humanity and genocide in the present and future. Those who oppose such laws are of the view that even if such denial is despicable, people have a right to question it. There are cases of false accusations of mass murder and therefore the freedom of enquiry to find out the truth should not be restricted.

At any rate, if we now return to the attack on January 7, 2015 by Muslim militants on the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo, which published scurrilous cartoons of the Prophet (PBUH), in which 12 people lost their lives — including the editor of the magazine, four well-known cartoonists and two police officers, one of them a Muslim — we have to concede that such behaviour is outright criminal and has to be condemned unreservedly. Even in Pakistan, where murderers of alleged blasphemers have in the past escaped punishment, things might be changing soon.

However, decent people are expected not to hurt the feelings of others. The cartoons might amuse some people but they most certainly deeply offend others. In fact, such cartoons have been making the rounds in many western states, including Denmark and Sweden, and one wonders why this should this happen again and again since each time some Muslims react violently. Can one possibly argue in favour of the blasphemy laws and censorship of publications to maintain the public peace? The Inquisition — the wars of religions in the 16th century that bled Europe white — victimisation of individuals under blasphemy laws and recurring minority persecutions, including the Holocaust, have created deep-rooted antipathy towards religious dogmas and totalitarianism. I think such options are out of the question.

However, I am just wondering if scurrilous cartoons can, by analogy, be considered a form of freedom of speech and expression, which J S Mill would find inflammatory as it causes extreme reactions from some Muslims and, therefore, should be criminalised. The weakness of this argument would be that since one is free to draw cartoons of all religious founders and since Christians, Jews and others do not react the same way as some Muslims do there is no basis for a general ban on such a form of artistic expression. Banning just the cartoons of the Prophet (PBUH) as an exception to the general praxis would be a contradiction difficult to justify. Of course we have the example of the fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini calling for the assassination of Salman Rusdie for his novel, Satanic Verses, which he declared as an insult to Islam and the Prophet (PBUH). So, banning just cartoons would not solve the problem.

There is of course the question of decency. One can expect from civilised people not to hurt the feelings of others. Most do not, and normally people do exercise self-restraint but that is a matter of discretion and good manners, nothing more. Since Muslims have settled voluntarily in the west they have to obey its laws, including those on freedom of speech. Alternatively, they can peacefully propagate their standpoint and if they gain the support of a majority in European parliaments they can have the law changed on this matter. The third option is to return to their countries of origin where such acts do not take place. Then, of course, one can learn to ignore such publications as acts of foolishness. Finally, one can create pressure on western societies to change their ways by refusing to trade with them. These are some of the approaches that can reasonably be adopted to deal with the menace of scurrilous cartoons.

My theory is that those who publish such cartoons do have a political motive: to provoke an angry reaction from Muslim extremists and on such a basis problematise the Muslim presence in the west. Many anti-immigration parties explicitly demand that Muslims should be sent back to where they came from. The publication of cartoons is music to the ears of Islamists. The most extreme groups exploit such occasions to advance terrorism. Even ostensibly peaceful ones look for all opportunities to polarise Muslim immigrants and the mainstream populations of western states. For example, during the September 2014 Swedish election, cadres of Hizbut Tahrir, an organisation committed to the establishment of global Islamic government, went around polling booths dissuading Muslims from voting. They were told to instead prepare for the revival of the Islamic government. All this does not augur well for relations between Muslims and non-Muslims in the west.

(Concluded)

The writer is a visiting professor, LUMS, Pakistan, professor emeritus of Political Science, Stockholm University, and honorary senior fellow, Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. Latest publications: Winner of the Best Non-Fiction Book award at the Karachi Literature Festival: The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed, Oxford, 2012; and Pakistan: The Garrison State, Origins, Evolution, Consequences (1947-2011), Oxford, 2013. He can be reached at: billumian@gmail.com

Curtsey: Daily Times, February 17, 2015

The writer is an author and a lawyer based in Mumbai.

ON May 29, the information and broadcasting ministry stripped away from India’s public broadcaster, the Prasar Bharati, all pretence to autonomy. It appointed a new director general of news, and instructed her to report directly to the ministry. The DG serves both All India Radio (AIR) and Doordarshan TV.

In 1990 was enacted the Prasar Bharati (Broadcasting Corporation of India) Act, 1990. But the requisite notification for bringing it in to force was issued seven years later on July 22 1997.

It is not overburdened with credibility. To begin with, Section 13 of the act sets up a committee of 22 MPs “to oversee that the corporation discharges its functions in accordance with the provisions of this act and … submit a report thereon to parliament”.

Is there any autonomous corporation in this sensitive realm in any democracy which has MPs breathing down its neck “to oversee” it? The chilling, inhibitive effect of the very existence of such a provision is obvious. Its implementation will have worse consequences.

The Prasar Bharati board consists of a chairman, an executive member, two others to deal with finance and personnel, six part-time members, including DGs of AIR and Doordarshan as ex-officio members and, indefensibly, a nominee of the information and broadcasting ministry, plus two elected nominees of the employees. They are appointed by the president on the recommendation of a panel consisting of the president, the chairman of the Rajya Sabha, and the chairman of the Press Council. The executive member will be the chief executive of the corporation.

Shortly before the act came into force, the Supreme Court of India gave a landmark ruling on Feb 9, 1995 which renders the act unconstitutional in two concurring judgements.

One said: “The central government shall take immediate steps to establish an independent autonomous public authority representative of all sections and interests in society to control and regulate the use of airwaves”.

The other amplified: “The broadcasting media should be under the control of the public as distinct from government. This is the command implicit in Article 19(1)(a) [the fundamental right to free speech]. It should be operated by a public statutory corporation or corporations, as the case may be, whose constitution and composition must be such as to ensure its/their impartiality in political, economic and social matters and on all other public issues.

“It/they must be required by law to present news, views and opinions in a balanced way ensuring pluralism and diversity of opinions and views. It/they must provide equal access to all the citizens and groups to avail of the medium.”

Both judgements agreed on the major premises underlying the order. “Since the airwaves/frequencies are a public property and are also limited, they have to be used in the best interest of society and this can be done either by a central authority by establishing its own broadcasting network or regulating the grant of licences to other agencies, including the private agencies.

“...[T]he electronic media is the most powerful media both because of its audio-visual impact and its widest reach covering the section of society where the print media does not reach. The right to use the airwaves and the content of the programmes, therefore, needs regulation for balancing it and as well as to prevent monopoly of information and views relayed, which is a potential danger flowing from concentration of the right to broadcast/telecast in the hands either of a central agency or of few private affluent broadcasters.

“That is why the need to have a central agency representative of all sections of society free from control both of the government and the dominant influential sections of society.”

The court also added, “This is particularly so in a country” where the majority of the population is illiterate. “When, therefore, the electronic media is controlled by one central agency or few private agencies of the rich, there is a need to have a central agency ... representing all sections of the society. Hence to have a representative central agency to ensure the viewers’ right to be informed adequately and truthfully is a part of the right of the viewers under Article 19(1)(a).” The citizen’s right to a truly autonomous public broadcaster follows inexorably from his right to free speech.

Thus private TV channels also owe a legal duty to maintain a fair balance. The airwaves are public property held in trust, as the US Supreme Court held in the ‘Red Lion’ case in 1969. “It is the right of viewers and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters which is paramount.” That right is legally enforceable against private broadcasters as much as against the state broadcasting corporation.

The writer is an author and a lawyer based in Mumbai.

Published in Dawn, June 13th, 2015

T2F Director Sabeen Mahmud. — White Star

A pair of sandals lies amid broken glass in a car after the murder of Sabeen Mahmud in Karachi, Pakistan, April 25, 2015. — Reuters

A policeman and security officer inspect a car after the murder of Sabeen Mahmud in Karachi, Pakistan, April 25, 2015. — Reuters

KARACHI: The director of The Second Floor (T2F), Sabeen Mahmud, was shot dead by unidentified gunmen in Karachi on Friday.

Sabeen, accompanied by her mother, left T2F after 9pm on Friday evening and was on her way home when she was shot by unidentified gunmen in Defence Phase-II, sources confirmed. She died on her way to the hospital. Doctors said they retrieved five bullets from her body, which has now been shifted to Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre.

Her mother also sustained bullet wounds and is currently being treated at a hospital; she is said to be in critical condition.

T2F had on Friday organised a talk on Balochistan: 'Unsilencing Balochistan Take 2: In Conversation with Mama Qadeer, Farzana Baloch & Mir Mohammad Ali Talpur.'

Sabeen had left T2F after attending the session, when she was targeted.

T2F, described as a community space for open dialogue, was Sabeen's brainchild. In an interview with Aurora, she referred to it as “an inclusive space where different kinds of people can be comfortable.”

Conceived as a bookstore and café patterned after the old coffeehouse culture of Lahore and Karachi, The Second Floor — or T2F, as everyone calls it — says on its website that it was born out of a desire to enact transformational change in urban Pakistani society.

Muttahida Qaumi Movement leader Nasreen Jalil, while talking to DawnNews, condemned Sabeen Mahmud's killing and demanded the government to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Sindh Chief Minister Qaim Ali Shah, taking notice of the incident, has asked the Additional Inspector-General Karachi Police to submit a report on the brutal murder, DawnNews reported.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM,

Karachi: Unknown gunmen on motorcycles opened fire on Hamid Mir in Karachi on Saturday, injuring the senior reporter and television anchorperson.

The incident took place on Sharae Faisal near Natha Khan area when the gunmen opened fire on his vehicle around 5:30pm.

The journalist was on his way to his office from the airport when he was attacked.

“Four gunmen riding on motorbikes started firing at the car near Karsaz (around six kilometres from Jinnah International Airport) when Mir's car was passing through, he received three bullets in the lower parts of his body,” said senior police official Peer Muhammad Shah.

Shah said a single gunman first opened fire on Mir's car, followed by others who chased him on motorcycles.

Karachi police chief Shahid Hayat said Mir suffered three gunshot wounds to the stomach and the upper legs.

“Hamid Mir has received three bullets but the doctors told me that he is out of danger,” Karachi police chief Shahid Hayat told news agency AFP.

Mir's colleague Rana Jawad said he had talked briefly to Mir on his mobile phone as he was under attack.

“I spoke to him briefly when he was escaping, he said they have shot him and now they were following him,” said Jawad.

“He has been shot thrice, in the pelvic, abdomen and thighs,” he added.

Mir was taken to a private hospital for emergency treatment. The journalist was taken to the hospital in a state of unconsciousness.

Following a surgery lasting two-and-a-half hours, hospital administration said the journalist's condition was stable, but that he would be kept under observation.

Friends and colleagues said Mir had previously told them that if he is attacked, Pakistan's intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), “and its chief Lt General Zaheerul Islam will be responsible”.

Speaking to Geo News, his brother Amir Mir said the senior anchorperson had visited him and informed him of what he called a plan hatched by Lt-Gen Islam to assassinate him.

Geo News, the media organisation for which Mir works, reported that he had also sent a recorded video to Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) implicating the ISI in any attempt on his life.

Meanwhile, a spokesman for the ISPR, the military’s public relations wing, condemned the attack on Hamid Mir, and said an independent inquiry must be carried out to ascertain facts behind the attack.

“However raising allegations against the ISI or the head of ISI without any basis is highly regrettable and misleading,” he said.

Shortly after the attack, messages of condemnation started pouring in against the attack the seasoned journalist's life.

In a message, President Mamnoon Hussain condemned the attack and expressed sorrow at the incident.

Social media also exploded with messages of condemnation.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, APR 19, 2014

Information Minister Pervaiz Rasheed speaks on the first day of the international media conference on Tuesday.— Online

ISLAMABAD: For a democratic country, Pakistan ranks worryingly high when it comes to the number of attacks on journalists.

Even though it is much better off than countries such as Iraq, Syria or Somalia that are torn apart by civil war and internal strife, Pakistan’s numbers of violence against journalists are comparable to these countries, Bob Dietz, the Asia Coordinator of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) told a sympathetic audience of journalists and media practitioners on Tuesday.

He was addressing the second international conference on Combating Impunity and Securing Safety of Media Workers and Journalists in Pakistan.

Mr Dietz deplored that the authorities in Pakistan had failed to move forward in this regard and had not been able to provide an environment conducive for journalists so far.

“Why can’t we make the situation better,” he asked, earnestly, adding that far too many journalists were getting caught in the crossfire between militants and the authorities. However, he recognised that the current regime had recognised the issue, referring to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s March 2014 meeting with representatives of the CPJ.

The government’s resolve was also evidenced by the presence of Information Minister Pervaiz Rasheed at Tuesday’s conference.

“We first met General Musharraf – who was the president at that time – and expressed concerns over violence against media. But he totally denied it and his minister termed the incidents ‘accidents’,” he said, adding that a similar response was seen when the matter was raised with President Asif Ali Zardari and the ministers of that era.

“Though there were some assurances made by the prime minister and his team, but I see that journalists are still not satisfied with the government’s measures,” Mr Dietz added.

Earlier, addressing the inaugural session, the information minister said that the whole nation was united in the fight against terrorism and the government was trying its best to find solutions.

“I would like mediapersons to come forward and help identify the culprits,” Mr Rasheed said.

His answer to almost all queries and criticism was swift and crisp.

“We would like to hear from the (journalist) community what the solutions should be,” he said.

When veteran journalist and former Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists president Mazhar Abbas questioned the minister about low salaries and job insecurity in media organisations, the minister invited him to a high-level meeting to guide the government on what it could do.

He also announced that a bill aimed at improving access to information under right to information principles would be presented in the next cabinet meeting.

Senior journalist Mohammad Ziauddin said the Afghan war actually came to Pakistan after 2005, but the media was not ready to cover it.

“At the same time, militants wanted to show their presence and pushed for space in the electronic and print media,” he said.

“The same method was adopted by ethnic, nationalist and sectarian parties – now the environment is dangerous and no place is safe.”

Senior anchorperson Hamid Mir quoted several anecdotes from his career, from 2006 onwards and narrated his own ordeal before and being attacked by unidentified gunmen in Karachi last year.

“A hit-list of journalists in Balochistan was floated by pro-establishment militants and this list was published in a report by the PFUJ, but even then, five of the people on the list ended up dead,” he said.

He said that it was time the government passed a law for the protection of the media.

“I do not say it will end the trouble, but it will be a first step towards a solution,” he added.

Representatives from the Open Society Foundations (OSF), United Nations’ Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco), as well as other countries from the region, such as Nepal, Afghanistan and Indonesia also participated in the subsequent panel discussion.

Ujjwal Acharya, South Asia regional coordinator for the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), said that in Nepal and Pakistan, a lot of people believed that the media was not credible. Talking about the importance of perceptions, he said that there was a need to build people’s trust in the mainstream press.

OSF’s Maria Teresa shared her experiences of working on journalists’ safety in Colombia and Mexico.

Published in Dawn January 28th, 2015

.—AFP/File

PESHAWAR: The year 2014 was the worst ever in the history of the country for the media, according to a report issued by Freedom Network, Pakistan.

The report says that 14 people related to media including journalists, media assistants and bloggers were killed for their work and scores were injured, kidnapped and intimidated in 2014.

The report titled ‘State of Media in Pakistan: Key Trends of 2014 and Main Challenges in 2015’ says that 2014 came to be characterised by a number of troubling developments in the realm of electronic media when laws were used formally to browbeat and censure it, according to a press release issued by Freedom Network, Pakistan.

Freedom Network( FN), a Pakistani media rights watchdog and an independent advocacy, research and training organisation, in its latest yearly report released on January 25, 2015, carries nine articles with in-depth look at issues of media security, impunity against journalists, worsening media ethics and crisis of credibility, outdated media laws, digital freedoms and privacy protections, social media and digitalisation of news sources, media ratings and profit motives, and mainstreaming of citizen journalism in the country.

“For several years now, Pakistan has consistently figured as the most dangerous of countries for journalists when it comes to the debate around freedom of expression internationally,” says FN managing director Aurangzaib Khan. He adds that a lot needs to be done to reduce the risk to human rights defenders, journalists and development practitioners in the country to make defending human rights and practicing journalism safer professions.

The report also investigates how 2014 came to be the deadliest year for Pakistani media for its shockingly high number of fatal casualties.

Each of the nine key media issues discussed by a separate expert on the subject ranging from seasoned journalists, dealing with these issues on a daily basis, to activists who keep a close eye on media developments -- each suggesting changes and reforms needed to promote greater media professionalism.

In her article on digital challenges to media in Pakistan, Nighat Daad has noted this disturbing trend. “The previous regimes in Pakistan preferred a behind-the-scene approach for controlling internet freedom but the [current] regime in its first 18 months in office has been vocal in the Parliament and on media for using strong measures to censor social media,” she writes.

Phyza Jameel, a media and development activist, researcher and analyst, has thrown light on the fast emerging social media in the country.

Published in Dawn January 26th , 2015

KARACHI: At least 48 journalists have been killed in the line of duty in Pakistan in last ten years and 35 of them were deliberately targeted and murdered because of their work. In 2012 alone, six journalists were killed in the country. For every journalist who has been deliberately targeted and murdered, there are many others who have been injured, threatened and coerced into silence, say a Pakistan Press Foundation (PPF) report released on Friday.

Pakistani journalists are killed, unjustly detained, abducted, beaten and threatened by law enforcement and intelligence agencies, militants, tribal and feudal lords, as well as, some political parties that claim to promote democracy and the rule of law. Sadly, the perpetrators of violence against journalists and media workers enjoy almost absolute impunity in Pakistan.

Of the 48 journalists killed in the line of duty during these 11 years, 14 were from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 12 from Balochistan, nine from Sindh, eight from Federally Administrated Tribal Agencies (FATA), three from Punjab and two from the federal capital, Islamabad.

Of the 35 journalists murdered since the year 2002 because of their work, 11 were from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 10 from Balochistan, four from

FATA, seven from Sindh, two from Punjab and one from Islamabad. Of 48 journalists killed, 25 were shot; three targeted in suicide attacks, seven killed in suicide bomb blasts, nine abducted before murder, while four killed in crossfire.

While formal criminal complaints (First Information Reports) were lodged, the murders of media workers were not seriously investigated or prosecuted. Over the last 10 years, the murder of Daniel Pearl, reporter for the US-based Wall Street Journal, was the lone case of murder of journalist in Pakistan where suspects were prosecuted and convicted. This is why Pakistan is among the list of shame prepared by the US-based Committee to Protect Journalists of those countries that do not investigate and prosecute murders of journalists.

Because of the Afghanistan war and the so called war on terror, areas bordering Afghanistan — Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan and FATA – are the most dangerous areas for journalists.

Journalists in FATA, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan work under extremely stressful conditions with pressure being wielded by security agencies, militant groups, district administration and tribal leaders.

In many instances security agencies or militant organizations require journalists to get ‘clearance’ from them before releasing their new reports. Journalists from Balochistan, in particular, face violence and threats from security and intelligence agencies, as well as, ethnic, sectarian and separatist groups.

Pakistani journalists are often caught between competing power centers. For example recently the Balochistan High Court directed journalists not to report news of banned organizations; while these banned organizations exert pressure on local media to give them ‘proper’ coverage.

The alarming increase in violence and threats has forced many journalists to migrate from these danger zones. According to some estimates, one-third of FATA journalists has already moved to other areas or gave up the profession.

Pressure and intimidation has forced the journalists to adopt a self-censorship, particularly in the conflict areas. Because of this self-censorship, the reports emanating from the conflict areas about military action by Pakistani law enforcement agencies, drone attacks by the US forces or attacks by militants are based on press releases and not on observations by independent journalists. Thus, not only human dimensions or horrors of the war being fought in Pakistan are absent from media, but reports that are published or broadcast also lack credibility. This has hindered the development of consensus on the path Pakistan should take to steer the country out of the crisis facing it for last three decades.

Free media is essential to democracy in Pakistan as it promotes transparency and accountability, a prerequisite of sustained economic uplift. The impunity enjoyed by those who attack journalists is seriously hampering press freedom in Pakistan and all stakeholders, including media organizations, the government and civil society should join hands to devise some mechanisms for ensuring safety of working journalists.

Pakistan Press Foundation (PPF) recommends the following steps to control the alarming rise in violence against media, and to end impunity for those who attack journalists and media workers:

1. Criminal cases should be registered, investigated and prosecuted against the perpetrators of violence against media.

2. An independent commission comprising professional media organizations, CSOs, press freedom and human rights organizations and professional bodies of lawyers should be established for monitoring criminal investigations and legal follow-up of cases of violence and intimidation of journalists.

3. Local, national and international print, electronic and online media should ensure long-term follow up of cases of assault on media organizations and workers

4. Journalists should be provided with safety and first aid trainings and guidance on how to report in hostile environment.

Journalists working in conflict areas should also be provided with guidance in recognizing and dealing with stress and post-traumatic stress.

5. Safety equipments including bulletproof jackets and medical kits should be given to journalists covering the conflicts.

6. Threats and attacks can be reduced to some extent by adopting a professional approach and impartial and unbiased reporting.

Journalists, especially those in rural areas, should be imparted trainings on writing skills, language proficiency, editing and interviewing techniques to enhance their capabilities.

7. Employers should provide journalists life and medical insurance and also compensation in case of death or injury related to their work. As Pakistani journalists are victims of circumstances that are both local and global in nature, the government should also compensate to the families of journalists, killed in the line of duty.

8. Proper medical treatment, including treatment abroad, should be provided to media workers who have been subjected to violence.

9. In addition to compensation by employers and government, funds should be set up for families of journalists who had been murdered or injured. These funds could be operated by the immediate families of the victimized journalists.

10. There is need to for media organizations to develop ‘operating procedures’ with law enforcement agencies that will allow journalists to cover the conflict situations with greater safety.

11. Arrangements should be made in all major cities to provide refuge and safe houses for the journalists who are forced to leave their homes so that they can live and work in safer cities.

12. Media organizations should interact with all stakeholders including government departments, political parties and groups and security agencies to develop strategies that promote safety of journalists and other media workers.

13. Employers should give journalists facing threats the option of transferring them to safer cities for extended periods of time. The remunerations during these periods should be based on the actual living expenses in these cities, which are generally higher than rural areas.

14. At times, insensitive and misinformed editors push their reporters and photojournalists into the situations where they have to put their life and well-being at risk for getting the stories. There is a need to create awareness and sensitizing the owners of the media organizations, as well as, those who are working on desk to realize the ground realities and threats being faced by the journalists working in fields especially in conflict areas.

15. Some international media organizations do provide proper safety trainings and equipment to their correspondents; however, journalists working for international media organizations as stringers or on freelance basis in remote areas of FATA, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan do not receive adequate training or support. As reporting for international media carries greater risk for these stringers, these organizations should provide security training and support, as well as, life and medical insurance for their stringers and freelancers working in conflict area.

Curtsey:The News, Sunday, November 25, 2012

Send email to nazeerkahut@punjabics.com with questions, comment or suggestions

Punjabics is a literary, non-profit and non-Political, non-affiliated organization

Punjabics.com @ Copyright 2008 - 2018 Punjabics.Com All Rights Reserved

Website Design & SEO by Webpagetime.com