| Memoirs: |

For whom the bell tolls |

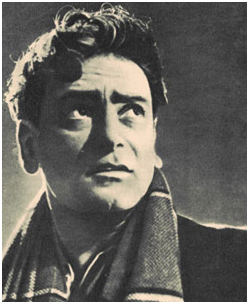

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

The ballad of Mirza Saheba’n

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

The 16th day of April 1853 is special in the Indian history. The day was a public holiday. At 3:30 pm, as the 21 guns roared together, the first train carrying Lady Falkland, wife of Governor of Bombay, along with 400 special invitees, steamed off from Bombay to Thane.Ever since the engine rolled off the tracks, there have been new dimensions to the distances, relations and emotions. Abaseen Express, Khyber Mail and Calcutta Mail were not just the names of the trains but the experiences of hearts and souls. Now that we live in the days of burnt and non functional trains, I still have a few pleasant memories associated with train travels. These memoirs are the dialogues I had with myself while sitting by the windows or standing at the door as the train moved on. In the era of Cloud and Wi-fi communications, I hope you will like them.

Illustration by Mahjabeen Mankani/Dawn.com

This is Danabad, a small village but a large monument of love, a tomb of reverence. Though the story of Mirza Saheba’n has been filmed, re-enacted and told many a times but something about this ballad, so fascinates the audience that it appears afresh, every time.

Danabad was home to the Kharal Jaats. Wanjhal, the tribal head, was blessed with a son, who was named Mirza Khan. Almost at the same time, in another village nearby, Mahni Khan, a Jatt Sardar from the Kheva sub-clan, was also blessed with a daughter, named Sahiba’n. According to some traditions, Mirza’s mother was sister to Mahni Khan and a few differ that she was sister to Saheba’n’s mother. Regardless of the maternal linkage, the story of Mirza and Saheba’n is the one of cousin love. By some twist of fate, Mirza was sent to live at Saheba’n’s place after the death of his mother.

From Haryana to Vancouver, and Fatehgarh to Victoria, whenever this ballad is staged, there are two scenes which initiate the story. The first is of a mosque, where a teacher tells Saheba’n to write Aleph, the first vernacular alphabet, but she wrote “Mirza” instead. The maulvi canes Saheba’n and the lash marks appear on Mirza’s back. The other scene is of a grocery shop, where the keeper loses his wits to Sahiba’n’s beauty. Baba says that a woman’s beauty is a moment of amazement, which just captivates the man.

The love story became public and shortly, was the talk of the town. Mirza returned to Danabad and Saheba’n was engaged elsewhere. When her wedding guests started pouring in, Saheba’n summoned Karmu Brahmin, an old confidant, and sent a message to Danabad. The message was her intent to fight against fate. Karmu covered the 40 miles and warned Mirza of the impending disaster, with a word that any delay might deprive him of the love of his life. At Mirza’s house, another wedding was in waiting, his sister had henna on her hands but Mirza chose to leave. Before he could ride Bakki, his mare, away, the women folk of the household gathered. They tried to dissuade him; unfortunately, love not only blinds vision, but also reason.

Mirza reached the village and with an aunt’s help, made a rope ladder. Saheba’n was instantly transported from her palanquin to his horseback. Soon the dholak beat was swallowed by Bakki’s hooves beat. The love lore of Mirza Saheba’n is incomplete without the mention of Bakki. Peelo draws her lineage to the six saddles that graced history. It included Duldul of Hazrat Ali, Hick of Gugga Chohan, Neela of Raja Rasalu., Lakhi of Dulla Bhatti and Sandal of Raja Jaymal. The others draw her pedigree from Guru Gobind Singh’s horse and yet others think that the stuffed horse, of Ranjit Singh in the Shahi Qila is also from the same bloodline.

With the glory she carried, Bakki well understood the situation. For the safety of her riders, she first halted short of Danabad, where a banyan tree awaited the ill-fated couple. Once Danabad was in view, thoughts of Kheva eluded Mirza’s mind. He could see the decorated haveli and the baraat of his sister. The same sister, who had held the reigns of Bakki and had warned Mirza of the dangerous women of Sials. Jatts, across Punjab, are fearful of their sisters so Mirza decided to head home once the wedding was over but fate had other plans. Soon, Mirza was asleep with Saheba’n awake by his side.

When the silence prevailed, she heard the hoof beats. Horses of Khan Shahmeer, her brother, were a rare breed and the riders appeared familiar. The dangerous woman of Sial thought for a while. If the riders were her brothers, Mirza was unlikely to spare any of them and she had never wished Kharal arrows for Kheva men. All she had wanted was the love of her life but did not perceive the prohibitive cost. In the split of moment, she broke the arrows and hanged the bow by the tree. When the fighters ranged closer, she woke Mirza up. Confident of his archery, Mirza still thought he could manage them all. He reached for his bolt and found the bent arrows and hooked bow. His great heart broke. Few opine that Mirza lost it to Sahiba’n’s trickery, before Shameer’s sword stuck him. Yet others record that he last called out Sahiba’n, instead of Kalima. Before the lights go out completely and curtains roll, Sahiba’n is also seen falling on the stage. Peelo’s voice feeds in the ambience.

Manda Keetoi Saheba, Mera Turkish Dittoi Tang, Ser To Mandasa Lay Gaya, Gal Wich Payendee Chand, Bajh Bharawan Jatt Mariya, Koi Na Mirzay Day Sang

O Sahiba’n! You did no good by hanging the bow on the branch (of the tree) The turban fell from the head and the face was puffed in dust The Jatt was killed away from the brothers as Mirza died alone

Besides Peelo, the story has been told by Mola Shah Majethvi. R.C.Temple heard this ballad from many local performers and preserved it in his book. A myth, other than the grave of Mirza Saheba’n, fills up the tragic romantic cosmos of Danabad. It is said that a young girl in every generation of the Sials falls in love and dies an unnatural death. Across the canal, the road and the railway line, Jhang also celebrates a similar tradition, courtesy Heer.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM— PUBLISHED APR 01, 2013

The death of a Maharaja

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

The Maharaja breathed his last on the fifth day of his sickness, the 15th of Asarh, 1896 (Bikrimi / Punjabi Calendar and 20 June 1839 Gregorian Calendar), Thursday, around dusk. It had already grown dark, Raja Dhiyan Singh, the Prime Minister was ordered to maintain calm in the city, in case riots broke out. The next day, in accordance with royal tradition, the dead body of the Maharaja was bathed and made up the way he appeared in court, in a royal dress and jewels. A podium of gold was prepared for his last rites.

His last two Rajput wives, Maharani Rajdai and Maharani Hardai, daughters of Raja Sansar Chand, ruler of Kaangra, started their preparations for Satti. At first, they declared all their estates and property including jewels, gems and stones to charity. Driven by the Maharaja’s love, they dressed up in their bridals and walked out of the palace, bare feet.

Amongst the men, Raja Dhiyaan Singh, the Prime Minister, declared that he would also burn to death with the Maharaja and ordered his effects to be given to charity. On seeing this, the nobles from the court came and persuaded him to change his decision. They pleaded that the Maharaja had chosen Raja Dhiyan Singh, amongst all men because of his wisdom and it was in the greater interest of Punjab that he looked after the affairs, run the state and guided the crown Prince Kharag Singh. Raja Dhiyan Singh, however, refused to listen. Prince Kharag Singh then, walked up to him and convinced him to change his mind. He offered him to leave the assignment as soon as calm prevails, to which he agreed.

Both the Ranis, moved out of the palace and sat around Maharaja’s dead body. Geeta, the holy book, was placed on the Maharaja`s body. The Satti Ranis administered the oath on Geeta and the body of Maharaja, by Raja Dhiyan Singh and Prince Kharag Singh to fulfill their duties for the best of Khalsa Raj and the Punjab Empire.

The Maharaja’s dead body was lifted with great prestige. Hundreds of gold coins, minted with the Maharaja’s figure, were thrown in the air. A large number of servants and citizens accompanied the funeral procession. The procession was taken out from the western gate of Hazoori Bagh and it moved alongside the River Ravi, where it was placed on a heap of Chandan wood for cremation. Prince Kharag Singh lit the fire. Both the Ranis sat in the fire, holding the head of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and 11 Kaneez (maids) sat on both side of the dead body, to be burnt with the Maharaja. Raja Dhiyan Singh went near the Ranis and requested for prayers for Prince Kharag Singh, the Sattis did not reply and stayed still with tight lips and closed eyes.

When flames flickered high, oil, ghee (purified butter) and scents were thrown in. A pigeon flew from nowhere and fell into the fire to become Satti. After a little while, it started to rain. The skies also seemed to mourn the death of the Maharaja. After the fire finally extinguished, the bodies of the Maharaja, Ranis and the maids had completely burnt and the rituals had been completed, Prince Kharag Singh took a bath and returned to palace.

On the 4th day, the remains (of cremation) were dispatched honorably, to Ganga. The remains were taken out in the form of a procession. All the courtiers, who attended the royal procession, paid their respect to the Maharaja’s remains. The reagents of the area, from where the remains passed on their way to Ganga, came out to pay homage. On the 13th day, when the remains were finally merged into Ganga, millions were given to Brahmins and the last rites culminated.

The crown prince ordered to build a Tomb (Samadh) and valuable stones were called for across India. The tomb was under construction, when Maharaja Kharag Singh died. A pause prevailed throughout the regimes of Maharaja Sher Singh and Maharaja Duleep Singh.

Finally, when the British assumed the rule of Punjab, the tomb was completed. Many people visited the tomb in the coming years. On account of the heaviness of the upper Dome, cracks were observed in the eight supporting pillars. When British administrators observed this, they contacted me and as In charge of the buildings of Lahore, I was given the responsibility to stabilise and restore the tomb. I added eight more supporting pillars and the cracking pillars were strengthened through iron rings. To date, the Samadh is stable and attracts visitors throughout India.

Excerpts from Chapter 44, Tareekh-e-Punjab by Kanhaya Lal Hindi Translated by Muhammad Hassan Miraj

Curtsey:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED NOV 09, 2012

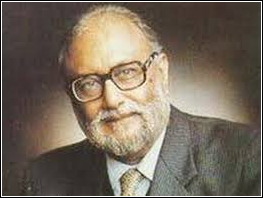

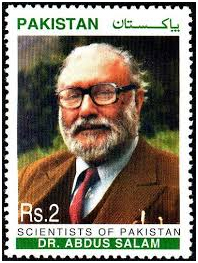

The Jhang of Abdus Salam

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

Other than Sultan and Chander Bhan, Jhang has references which the national history has chosen to forget. One such reference is Dr Abdus Salam, who is intentionally being erased from public memory, unfortunately, on accounts of religion. Official historians stumble upon his reference much similarly as they deal with the chapter of genetics in advanced biology textbooks; staple it and think it forgotten.

Born in the small dwellings of Santok Das, Abdus Salam spent most of his childhood in Jhang. His grandfather was a religious scholar and his father was an employee in the education department and so, it was the mainstay in Abdus Salam’s household. There are rumours that his parents saw a dream forewarning them about his illustrious career and then there are stories about him being taken to school for admission in the first grade but qualifying for the fourth grade instead. Regardless of these anecdotes, his academic life was indeed, a matter of honor. When anyone inquired about his young age and distinction in examinations, he simply raised his finger and pointed towards the sky, attributing it towards Allah. Those were the times of the Raj and religion was a private affair, rather than now when it is determined by parliamentary committees under the influence of protests.

Despite his love for literature, Salam took up sciences when he joined college. He opted for this route for qualifying for ICS, a job much envied by his family but after being turned down on medical grounds; he decided to pursue further education. Cambridge University, those days, offered scholarships for which Abdus Salam applied, despite his frail economic conditions. Between the benevolence of Sir Choto Ram, a minister in the Punjab Government and Abdus Salam’s luck, a candidate dropped off from the final list. The much desired Cambridge scholarship, for which people applied for months in advance and prayed for days, now belonged to him. That year, when people across the world arrived at Cambridge with their expensive effects, a young man from Jhang with his sole steel trunk was also amongst them.

After the completion of his Masters degree, Abdus Salam was offered scholarships for further studies and various employment opportunities but Pakistan was a free land now and it needed men like him. He came back and started teaching at the Government College, Lahore, his alma mater. He taught mathematics in the morning and coached students for football in the evening.

Dealing with differentials and equations in the first half of the day; and taking the lost team for Doodh Jalebi to Chau Burji at night, this young professor was certainly not the two sides of the coins but rather a prism which imparted seven colors to every incident ray. Lahore was subject to anti-Ahmadiyya violence in 1953 for the first time and it cut Salam off his base. He, like so many others, was at a loss of identity.

A month later, he was offered an instructional post at the Imperial College, London which he accepted. The 30-year-old, youngest ever assistant professor of Imperial College, London, was a Pakistani now.

Having settled the Martial Law issue and the political manipulation, Ayub Khan arranged for Abdus Salam’s come back. He is credited for drafting the first comprehensive scientific policy. Abdus Salam went on to found SUPPARCO and arranged for scholarships, which helped hundreds of Pakistani scientists’ to educate themselves abroad. Making PINSTECH, Karachi Nuclear plant and Atomic Energy Commission, a reality and leading the IAEA mission, Abdus Salam set the grounds for scientific research. Many research institutes, from where hundreds of Islamic missions take off for reformation every now and then, were once founded by this non-Muslim scientist. Regarding his contributions towards Pakistan’s nuclear programme, he was instrumental in the Multan meeting and initial research but when the Bhutto government declared Ahmadis non-Muslims, he left for England. Despite the change in countries, his heart never changed for Pakistan and he kept guiding all scientists involved in the programme till he breathed his last.

He was offered the nationality of all those countries whose asylum seekers, today, lead the criticism on his faith. On being asked that why he avoided Pakistan, he replied, it was not him who avoided Pakistan but Pakistan that avoided him.

Abdus Salam’s credentials of were finally acknowledged by his nomination for the Nobel Prize in 1979. He worked for the Grand Unification Theory that declared a single source for all forces. When the prize was announced, he offered nawafil in gratitude. On the day of reception, Stockholm saw for the first time a recipient dressed in the Pakistani national dress, reciting Soorah Mulk in the acceptance speech.

Then return [your] vision twice again. [Your] vision will return to you humbled while it is fatigued. Chapter 67: Verse 4

The same year, the Pakistani government, rewarded him with the highest civil award. It is not the case that the state had not valued Abdus Salam but his vision and farsightedness was on a constant colliding course with our resources, rigidity and short shortsightedness. The government did honor him by issuing a postage stamp but when he proposed the making of a centre of excellence for research and technology, the then finance minister turned it down, declaring that the country could not afford a luxury hotel for scientists.

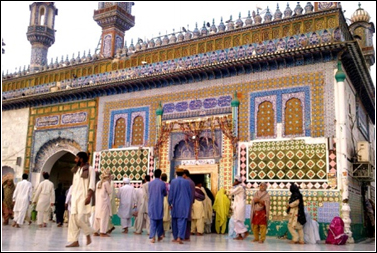

After he had received the Nobel Prize, he chose to visit Lahore, first. On landing, he headed straight to Data Saheb and then went to the Government College, Lahore. His humility held both the places with equal reverence and despite his 300 plus awards, he remained the same Abdus Salam of the yesteryear's, attributing his all achievements to God. In a public gathering, someone commented that Jhang was initially famous for Heer and now will be famed for Abdus Salam’s Nobel Prize. He remarked that there are hundreds of Nobel Laureates but only one Heer.

While Abdus Salam opted to be buried Pakistan, little did he know that he would require a magisterial permission for his tombstone. Abdus Salam might have believed that if the Quaid’s speech of 11th August 1947 had finally found its way, his speech of 1944 at Srinagar would also be made public one day.

Besides the salinity, the fertility of Jhang is being ravished by something else as well.

Prior to Chandar Bhan, Jhang belonged to Sultan. This mystic was born in February 1628 in the area now known as Shorkot. Nature had already lined up the arrangements for the spiritual to be brought up as his mother, Raasti bibi, known for her piety, who taught him the basics of spiritualism. Hazrat Sultan Bahu did not acquire formal education but according to a tradition, his quest for knowledge was satiated by illuminated dreams. His devotion to God and love for His creations is evident through Sultan’s verses which are part of every Punjabi household.

To-date every student of mysticism begins his journey with the much revered “Aleph Allah chanbay dee booti” and graduates to “Dil darya samundroon doonghay”. These verses illuminate the inner self so as to see the human heart match the depth of oceans. Despite being Sultan-ul-arifeen (the king of the pious), the devotees who visit his shrine in Garh Maharaja, are first expected to visit the grave of his parents.

The mystery of Jhang revolves around the trinity of mysticism, love and poetry. Alongside Sultan Bahu, many other shrines populate the city. While the Muslim spiritual quest was enlivened by the shrines of Hazrat Shah Shiekha, Peer Jabbo Shareef, Shah Kabeer and Rodo Sultan, the Sikh Darbar of Guru Nanak Dev and Hindu temple in Ware Sulaiman tended to the other faithfuls.

Besides the tombs of holy men, a monument of love also adorns the city. However, unlike other shrines, the soul interred here did not belong to a saint but a lady. For the cultural world, she is the Heer of Waris Shah but if any Sial is consulted, he would swear upon her chastity. The story goes as a lady from the Sial family, Mai Heer, was famous in the entire region for her spirituality. When the political struggle between the Nauls and Sayyals geared up, the former decided to demean the saint woman. They made up a story which defamed Heer and her love for God was propagated as her love for one of her disciples, Ranjha.

The shrine of Sultan Bahu.

Originally, the story of Heer was written by Waris Shah in 1776, but a letter is said to have been written, by a historian to Behlol Lodhi, the ruler of Punjab, much earlier. This dispatch explained the reality of Heer and the conspiracy of the Nauls. It also explained how, entertainers, puppeteers and bhaats were employed to present this story as true. However, time did prove her innocence as all attempts to defame her failed. The efforts to malign her eventually glorified her love and earned her respect. True love, be it mortal or immortal, leads to God and has His will.

The details of Waris Shah have been covered in the episodes of Sheikhupura but the story of his story remains to be told. This chronicle of love between the Dheedho of Ranjha and the Heer of Sayyal is similar to the love stories across the world. There are, however, a few aspects which make it remarkable.

When Ranjha had a word with the mullah for spending a night in the mosque, it was in fact the dialogue between man and religion. His argument with sailor Luddan for crossing Chenab is the discourse between the material world and the ideological world. The detailed description of Heer’s beauty is an excellence of narration and Ranjha’s stunt as a shepherd for 12 long years is the embodiment of negation of self. His soul searching Joge and talks by Balnath are the reflections of the human mind and his arguments with Sehti at Khera’s village are the illustration of human belief. When Inayat Hussain Bhatti, recites the kalaam to the point that Heer laments the arrival of Ranjha at her village

Rab jhooth na keray jay hovay Ranjha, Taan main chor(d)e hoyee menun pattya soo

Translation

And if (God forbid), it is Ranjha, I am doomed and ruined

Listeners can visualise Heer stumping her head against the wooden door. Inayat hussain’s recital infuses such an expression that Heer comes to life. Her creased forehead, teary eyes and repentance struck body, appears so real that one could reach out and touch her. Towards the end, the sudden death of the two lovers highlights the futility of this world. Heer Waris Shah, to say the least, is not a story but a wondrous world.

The desert-like environ of Jhang is so fertile that the city lives up to its creative tradition without fail. The day to day dialogue carries such humility that when these expressions are disciplined into poetry, it causes heartache. The poets who crafted these piercing impressions are the third angle of the Jhang trinity.

When Riaz Ahmed migrated from India and made Jhang his home, he had never thought that making a life here would cost him his life. His constant financial fears did not hinder his creative sojourn initially but crippled him eventually. Riaz, who took up the pen name of Ram Riaz was too sensitive to stand against sickness and poverty. Lost to a routine that clipped his imagination, he lived a life of misery. The idealist was reduced to a subsistence amount of a mere 500 rupees per month from the Academy of Letters, so he resigned to death along with his imagination,

Jaanay kia kuch dil pey guzri, aaj jo dekha yaro’n ko, Kaisi mitti chaat gayee, in pathar ki deevaron ko

Translation

My heart skipped a beat as I saw my old friends today, Giants of yesteryears had been reduced to mere dwarfs

The second poet from Jhang is Majeed Amjad. This marvelous poet wrote many awe-inspiring poems but published only one book in his life. His anthology of poems was named as Shab-e-Rafta (A night gone by). Most of his work was compiled after his death. Fame came but after the hour and this sensitive soul did not live to see it.

Mehaktay jaatay hain chup chaap, jaltay jaatay hain, Misaal-e-chehra-e-paighambaran gulaab kay phool

Translation

They give away fragrance by smoldering their inner self,

Much like the prophets, the roses bloom

In pessimistic times such as ours, any poetry has to be diversely realist and feasibly pessimist to claim relevance. It has to be themed according to our lives. For those who fell in love in past decades, Shaam kay baad is one such expression that has many hearts tied with those words.

Tu hay sooraj tujhay maloom kahan raat ka dukh, Tu kissi roz meray ghar main utar, sham kay baad

Translation

You, being the sun, have no idea about the miseries of the night, Grace my house some day, when the evening falls

Mesmerising the youth with his description of death, Farhat Shah is also a poet from Jhang.

I felt that the entire city lives under the ambience of love. It might have been because of the madressah of Maulvi Imdad Ali where Sahiban and Mirza studied together and after Mirza left for his village, Sahiban never returned to her class. It might have been the handlooms, which as late as 1950s, existed in every house of Jhang and every Jhangvi was skilled in tying the two ends and knitting it together.

Across the railway line, a faqeer sang, solving the equation:

Assi Jhang da vaasi lok sajjan, Saada dil darya, saadi akh sehra

Translation

We, the people of Jhang, are friends forever, Our hearts resemble the rivers and our eyes, the deserts.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED JUL 02, 2013

Ganga Pur and Lahore

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

An old banyan tree stood somewhere around the city. Its shade hooked up the travellers who sat down and retired for a while before resuming their journey. Then, they cut the banyan and those who sat under its shade moved elsewhere. There are trees now but no more travellers. Despite its betraying nature, there are few men who yearn for these shades, and in defiance to the turn of events, they refuse to part with this memory. That, precisely, is the reason that folks as old as that tree, remember Jaranwala with awe. Away from the business capital of Faisalabad, lies the silent yet growing city of Jaranwala, much like a beaming bride, part unaware of her beauty and part conscious about it too. But Jaranwala is incomplete without a few mentions.

Next to Nankana, is the railway station of Buchiana, a small grain market, where life is all about fields and yields. Here, in this vicinity is a village, far more fertile than the lands of the bar. Though, the divinity of Ganga is restricted to the other side of the border, any resident of Ganga Pur can see beyond the futile divisions of colour, caste and creed. This, devout disciple of Ganga and Ram was Sir Ganga Ram, who built Lahore as we see it today.

Fondly remembered as “man of all the seasons”, this Sufi is close to every Punjabi heart. Those who spend their days and night, practicing medicine at the Ganga Ram Hospital and those who wait for their visa to fly abroad know him alike; no one escapes his signature. Whether posting a letter at the GPO or answering a summon at the High Court, visiting the courts of Faisalabad or benefitting from the powerhouse of Renala Khurd, walking around the Saigol Hall of the Aitcheson College or waiting at the Albert Victor wing of Mayo Hospital, the name of Ganga Ram finds a reason to leave a footprint on your heart, just like these buildings.

Born in 1851 to Daulat Ram, a police official in Mangtanwala, Ganga Ram was eldest of his siblings. He spent his initial years at Amritsar and after graduating from Government College, Lahore, joined Thomson Engineering College, Roorki. He was appointed Assistant Engineer at Public Works Department, Lahore employed on completion of his education.

I asked the old man about the definition of “Rizq”, he replied. “Those with the worldly vision take Rizq as mere subsistence whereas, in the actual essence, every good thing that comes your way, be it a fellow passenger, qualifies for “Rizq”.

Whether Ganga Ram thought this way or not, here at PWD, he met Kanhayya Lal Hindi and Bhai Ram Singh. The aristocratic grandeur around the Mall, which now defines the Raj era, was christened by this trinity. These three men were not only gifted in their craft but knew well how to fuse one culture with another duly supplementing the inherent beauty of each.

India, in those days buzzed with the British talent hunt. The Raj looked for able men and Ganga Ram was soon discovered. He was sent to England for advanced training in structural engineering. On his return, he was greeted with luck and fame. Serving as the executive engineer for Lahore, for almost 12 years, he commissioned many monumental works. The National College of Arts, Aitcheson College, Dayal Singh Mansion, Hailey College, Lahore High courts, Lahore Museum, Lady Maclagan High school, Widow House at Ravi Road, and the Lady Maynard School of Industrial Training are a few among them. The lining of trees astride the Mall Road, planning the first sewerage scheme for the city and developing Model Town were also the marvel of his town planning genius. Conclusively, it can be said with convenience, that before Lahore grew into a double story joy-ride, the city owed its beauty to Ganga Ram’s craft.

On retirement, he was made the Governor of the Imperial Bank of India. After a few months, he found it too boring to continue and joined the Patiala State Service. As head of constructions, he administered historical works like Ijlaas-e-Khaas and the new Moti Bagh Palace.

Despite his life in cities, the countryman inside him refused to settle down. Lahore, with all its vastness, had failed to charm him. Far and away, Chenab Colony awaited him and the life he brought along. Originally the revenue record, on that white cotton latha, registers this place as Chak 591 G B (Gogera Branch) but since Ganga Ram acquired it from the British authorities and rehabilitated it, the village has been named Ganga Pur, a tribute to Sir Ganga Ram. This vast expanse of land stretches over thousands of acres laid barren. Gogera Canal flowed through this area but irrigation was not possible because of difference in the water level. After analyzing the situation, Sir Ganga Ram decided to lift irrigate the village through a heavy motor. The machinery was transported through rail from Lahore to Mandi Buchiana but could not be brought to the village. A special 3 km long track was laid which was completed in 1898 but the train that traversed this track was different. Instead of puffing engine, it was pushed by huffing horses. After the motor was installed, the metamorphosis began and within six months, everything turned green. The efforts of Ganga Ram had converted the barren land to fertile fields. These 90,000 acres of arable land were the largest private enterprise of its time.

An engineer at heart, he carved a heart of gold for himself. After he turned the sand into gold, he started sharing the bounties with the lesser children of God. Built in 1921 by an amount of Rs 1,32,000, the Ganga Ram Hospital to-date remains the last hope of many poor patients. Alongside the hospital, he built the first widow house in Lahore and, here too, religion remained a non issue.

Ganga Ram died in 1927 in London. He was cremated there and his ashes were brought back to Lahore, where the whole city mourned this great philanthropist of his time. On the banks of Ravi, abaradari, with a dome atop, marks the burial place of Sir Ganga Ram. It was the site of Baisakhi celebrations, pre-partition. After 1947, however, there is no such gathering. Festivities go on but the spirit has faded away.

On the right side of the track, lies Khurdianwala, a town about to grow into a city. The town has an amusing story. Sher Shah, the Suri King, ordered a well to be dug at the site of the rubble. Once both the words combined, the name of the city was carved. It is now famous for textile mills, heavy industries and a warning shot for Lyallpur or Faisalabad.

Amidst this all is Jaranwala, a 400 years old city, famous for its fields and canals. The history of city is inscribed on a gate called the Pakistani Gate. Amongst other old things, it has a jute mill and a Jamia mosque. The mill has been abandoned and the mosque has grown. Before the partition, the city had three temples. Two of them were razed and the third one, with its frescoes and carvings at the basement, awaits encroachment. Located next to the National Bank, this temple is an archaeological site and can be visited anytime, subject to will. A more deliberate look reveals the demolished Burji’s.

Apart from temples, there was a marhi, which has now been converted into a girls’ college. A sizable population of the city resides abroad. Fewer are those expats whose parents lived here prior to partition and still miss this grain market.

When the train rolled from Ganga Pur to Buchiana, many locals benefitted. The water reached the fields and travellers hit their homes. After functioning for almost a century, it broke down. Residents of Ganga pur looked up in the sky and towards the state but neither the God sent any Ganga Ram, nor the state formed a committee. They decided to help themselves and within a few weeks, the horses pulled it again, last year.

On arriving at Ganga Pur, I realised the difference between the urbans and the rurals. Ganga Ram brought water to this village and the villagers gave up their name for him; he spent his life beautifying Lahore but the citizens could not take care of even a statue.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED MAR 18, 2013

The River that played god

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

Photo Credit: Imran Nafeel

The charm of Tilla Jogian and Rohtas is preamble to Jhelum. The city casts its spell, slowly and unknowingly, like love in the later life, tempting yet destructive. The city dates back to countless BCs and there is no account of who actually founded it. Its history and that of the river supplement each other, much like an umbilical cord. The magic of the city precludes talisman of the river.

Besides Indus, which is sacred to most inhabitants of its basin, Jhelum also finds its mentions in Hindu scriptures. Vyeth, Vatista and Hydespes are few names of this river, which according to Vedic scripture, is a source of purification for India. These days, however, it is the source of hydro-power. According to Greek mythology, the river is named after the god, Hydespes, whose parents controlled sea and cloud and whose siblings mastered rainbows and winds. Historians are divided on whether the river was named after the god or the god was named after the river. Despite this myth, reality and tradition, those who have lived by it, believe there is something divine about it.

Verinag, the spring source of Jhelum, is around 80 km from Anant Nag. After the Moghuls made their summer capital at Kashmir, they developed this place into a garden and reshaped the spring into an octagonal structure. From the mountain ranges of Pir Punjab, the river traverses long distances through Saupore, Bara Mola and enters Pakistan at Muzaffarabad. Before irrigating the land of pure, it brings life to Indian lands. The nature has no immigration procedure.

Throughout its course, the river flows past structures, humans and emotions. These sparkling waters have stories to tell but we, the unfortunate children of God, have no time to listen. It wants to tell how it fills the Wooler Lake and also the story of how a king built a small island in the middle of the lake. Another story is about the girl who cried while pedaling alone near Saupore. A tale of a love affair caught between communal strife in Srinagar. A word about the old man at Muzaffarabad, who, after having lived his whole life abroad, has come home to die. However, it does not tell at all about the agony of its riverbeds being excavated for sands to construct shopping malls. The river falls in Chenab at Trimmu Headwork.

Jhelum city was passed on to Sikhs from the Moghuls and eventually came under Raj. The imperialism of the city can be related to the British-style of town planning. The whole city was planned on both sides of the railway line. Hospital, Post office and Garrison developed on one side and the city on the other. A clear demarcation existed between the White man and his burden.

The year of 1857 changed everything about India. Peshawar uprising was curbed with relative ease due to mail censorship and initiatives by the British officers, however, Jhelum appeared as a center of resistance. Thirty-five British soldiers lost their lives. After the order was restored, a plaque was erected at St. John Church to commemorate the lives laid for the Queen mother. The lives laid for our Moghul King, however, find no mention in the history and were lives lost in the real sense.

Nothing much has changed ever since, only that GT Road is the new boundary between the trimmed lawns of garrison and roughly drawn fields of Tahlianwala. In the year of 1873, John Galwey designed a magnificent bridge across river. These days, an imposing hotel, rather the bridge, catches the eye with the promise of rented limousine for wedding ceremonies.

On the other side of the river, is the Inn founded by Moghul king, Aurangzeb Alamgir. It goes by the name of Sara-i-Alamgir. During the First World War, the British realised the military potential of the place. To honor the veterans of Jhelum, a school was planned to provide free education for their children. Inaugurated in 1922, King George V Military School Jhelum was renamed Military College Jhelum after independence and is now known as MCJ. Mostly, the sons of junior commissioned officers study here and after undergoing the selection procedure, join the Pakistan Army. The students of MCJ, known as Alamgirians, have both the attributes in their upbringing, the quest of a student and the vanity of a soldier. Inside the college gates, the world is very different. At a place where Alamgir once provided for the comfort of travelers, an old teacher of language, now provides for the development of his students. Professor Bashir, an instructor with an experience of over 40 years, aims at mending the hearts rather than the sentence structure of Alamgirians.

The city of Jhelum lays claim, not only on the fallen soldiers of the British Infantry, but also on the three brothers Mati Daas, Dayal Daas and Satti Daas, who laid their lives for Guru Taigh Bahadur during the Sikh persecution. Major Akram is another valiant scion of Jhelum who sacrificed his life for the country while fighting against the Indian army at Hilli in 1971. Strangly enough, the Nishan-e-Haider recipient of Pakistan and the Padma Bhushan recipient of India, Lieutenant General Jagjit Singh Aurora, both hailed from Jhelum. The narrow alleys of one of the mohallah, still remember the young Inder Kumar Gujral, who later rose to become Prime Minister of India. While he excelled at statecraft, the younger brother Satish Gujral learnt to draw and carve, making his name as a sculpturist and artist.

Nasser Azam, another artist, moved to England at a young age but Jhelum is still fresh in his memory. Sometime around partition, Balraj Dutt, who lived by the banks of Jhelum River, migrated to live by another river bank, Yamuna. He later took it to acting and was famous as Sunil Dutt. History is like a tornado and its might prompts it to possess short-term memory. The people of Jhelum, no more remember the kings and the generals, but a saint called Mian Muhammad Bakhsh. The mystic poet, who penned “Saif Ul Malook”, is held in reverence by many throughout India and Pakistan. The master-piece revolves around the story of a Prince, who fell in love with a fairy. Fewer believe that the couple still lives in one of the caves in the scenic tourist spot, north of Pakistan. Somewhere on the banks of Jhelum River, I once heard a shepherd, reciting his verses. Beneath the words, a subtle message was being conveyed to the soul through the subconscious, a message which was simple yet thought provoking ...

Loay Loay Bhar Lay Kuriyay Jay Tu Pani Bharna Fill in your pot with water, if you intend so Shaam Payee Bin Shaam Muhammad, Ghar Jaandi Nay Darna When the sun will set, you will fear going home alone ...Mian Muhammad Bakhsh

Curtsey:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED AUG 13, 2012

The town of soldiers and saints

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

Rohtas Fort near Jhelum – Photo courtesy Creative Commons

The train is supposed to move from Dina to Kaloowal and Kala Gojran to reach its destination, Jhelum, but it does not. Like most of the mythologies still in narration here, a mix of haunted voices, captivates the traveler and paralyses his intentions. There is indeed something magical about the cities that flourish on the hills and by the rivers.

In the dusty record rooms of revenue department, log books mention a reservation, Boorha Jungle, next to Dina. A road departs from this place to a wonderland called Rohtas. The weary bridge on the river Kahan is reminiscent of the cultural amnesia of the nation. Constant deprivation of basic amenities has devoid us of aesthetic curiosity. The sense to curate, preserve and educate on the cultural history is non-existent. Once a part of GT Road, Rohtas lost its clout after British engineers altered the ancient route. The fort also suffered as the road drifted further right.

On an expanse of about five kilometres, it is one of the architectural master-pieces of the sub-continent. Within the confines of invincible walls, a small populace inhabits this place, since the construction started, and marks its time calmly. These few good men have refused to believe that times, like the waters of river Kahan, have changed. They are Punjabi alternative to the abandoned soldiers of Alexander, dwelling in Kailash, who live on the Macedonian promise to return one day.

The tradition of developing two cities with the same name at the extents of the conquered empire was quite in vogue those days and Sher Shah Suri was no exception. To compliment the Rohtas Garh on the far side of his kingdom in Bihar, he developed this sleeping beauty and named it Rohtas.

The story of Humayun’s succession is rather interesting. The young prince fell ill and had little chance to survive. Babar was told about the Indian tradition of offering something substantial to affect a change in divine decision. The nobility at the court thought he would offer Koh-i-Noor but he was a father of another kind. An avid reader of Rumi, he declared that he could not present stones to God and the only thing worth the life of Humayun, was his own. The Padhshah of India is said to have spent all night on the prayer mat and in the morning circled the bed of ailing Humayun. Within hours, the prince started showing signs of improvement and the king fell sick.

The throne had cost Humayun his father but India has always been asking for more. Sher Khan, a vassal of Mughals formerly, took up arms and dared him for a decisive battle. The battle did come at Qannauj where Mughals were badly defeated. With a view to block the Northern route and minimise chances of Humayun’s retreat, he ordered a fort to be constructed. Most of the orders issued by the Suri King took little or no delays in implementation, the fort construction, however, was taking long. The local Gakhars had promised their allegiance to Babar so they refused to facilitate the construction. In a fist of fury, Sher Shah pledged to nail Gakhars for the world to remember. Now that the Gakhars have settled abroad, the fort is still a reminder of Afghan fury.

After the Gakhar’s denial, Sher Shah brought forth the man, we now know as Todal Mal. A Kaisath Khatri by caste, he announced that anyone who brings a brick would be rewarded by a gold coin. After few weeks, people worked all day only to earn a copper penny. What Soori sword could not win, Todar Mal coins secured. Despite his love for nailing Gakhars, Sher Shah did not live to see the fort completed. Todar Mal, like a good technocrat, had no difficulty in mending fences with Mughals.

In spite of being a trusted governor of Sher Shah, Todar Mal quickly gained acceptance in Mughal court. He ascended to the coveted post of Revenue Minister and subsequently was inducted in Nav Ratan (A council of nine gifted intelligent people that Akbar always kept his side). Todar Mal introduced many reforms in India. He standardised all the measurements, promoted Persian as official language and conditioned the rate of revenue with the produce in each season. His standard system was based on barley corn and was adopted by East India Company. The same was approved by Sir Thomas Munroe and is still practiced in most of the rural India. Though Sher Khan tried his best to block the Mughal entry into India, but the fate of Indian sub-continent has never been an individual decision, alone. A few years later, Sher Shah died and his empire succumbed to rivalries. Humayun marched back to revitalise the house of Mughals. The fort which cost almost a quarter of a billion, welcomed Humayun with Ghakahrs by his side.

Even if it was possible to evade the sensation of Rohtas, reaching Jhelum remains a dream. By rain-washed garrison, moist alleys and the hustling city, a road leads to Darapur, unnoticed. Passing through Sanghoi and Radiyala Hardev, it reaches Tilla Jogian. There are more stories attached to this hill feature than what appears. These narratives are seconded by the historical manuscripts as well as local myths. The teela has been the seat of Budhist monks, the first school of Ayurvedic medicine, the temple of Sun-god and the meditation centre for Kan Phatta Jogis. Ranjha came here to become a Jogi under Guru Gorkahnath and so did the hero of another folk lore, Pooran Bhagat. Guru Nanak Dev sat here for forty days in solitude. Alexander addressed his troops before marching any further. The ruins of balcony constructed by Ranjit Singh in remembrance of Guru Nanak Dev and the temples and baths, built almost a millennium ago, can still be seen.

The famous historian Al-Beiruni also visited this place and lately there was a rest house which now stands abandoned. But this fact sheet is for the historians and archeologist, what satiates the soul is the solace it offers and the spell it casts…on lion-hearts and broken-hearts, alike.

Reaching Jhelum has never been easier. With soldiers and saints en route, either you have to lay your life or pledge one.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM PUBLISHED AUG 06, 2012

Uch Sharif: Alexandria on the Indus

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

Chani Goth Station

Between Ahmed Pur East and Liaqat Pur, the rail halts at Chani Goth, a century old railway station that has managed to contain countless stories in the hollows of its domes.

These mysterious tales of reflective emotions are only to be told to the wandering gusts of wind. A century ago, this town was famous for the best of Gurr that would travel across India but it wasn’t until a year ago that the town regained fame. This time, for unspeakable violence.

In July 2012, when the handicapped Ghulam Abbas was alleged to have desecrated the Quran, the religious party with the claim to revive sunnah, motivated people through fiery speeches and invoked a sudden realization upon the faithful.

An hour later, the charged mob attacked a police station, dragged the accused out of custody, tortured him until his death and set his dead body on fire. All this in the central chowk of Chani Goth. After six hours, when the traffic had restored to normal on the national highway, the burnt body of Ghulam Abbas lay outside the police quarters of the town. The citizens went to bed that night in peace; the prestige of faith restored. The city, however, did not sleep for it had lost today the sweetness of its Gur to smoke and tears.

The Shrine of Bibi Jiwani at Uch Sharif. Photo by Humayun M

A little short of the convergence of the five rivers, where the Indus meets the Chenab to flow southward stands Seet Pur, another century old settlement. Next in the river-guard is Ali Pur, a small town with a namesake in Karnataka. Ali Pur manifests Iranian culture in India in a manner that travels from Ras Kumari to Leh. Jatoi, is another town in the same perimeter, with a public school that has aged alongside the railway station of Chani Goth.

Across the Indus is the sleepy town of Jam Pur. Initially, called Jadam Pur, for the Jadam, a subcaste of Aheers that had settled here ages ago. Groomed in the prophetic profession of goat herding, this Jadoo-bansi tribe had linkages with Samma and the Rajput Bhattis. Years ago, the carved pens of Jam Pur were a souvenir but as the original name of the place sank into oblivion, this memento was also lost to time. This was the time when authors read and the learned wrote – a phenomenon that was to be reversed later.

The criss-crossing riverine is home to the innumerable stories that range from those of the Hoat Baloch tribes of Kot Addu to the ancient city of Muzaffargarh. These unforgettable tales are either cloaked on account of divine compromise or due to mortal negligence. However, the epics are predestined to create new history whenever they will be retold to newer generations.

Ethically, the mention of all the stopovers enroute to Sindh is mandatory but the description of Uch Shareef is almost a religious obligation. Despite the sleepy sands of space and the murky waters of times, Uch Shareef has been extraordinary since its inception.

It is said that when Alexander passed through this place, he was awestruck by the confluence of the rivers. The Macedonian had heard from his folks that cities established on the coming together of rivers, prospered till eternity.

What remains common to all successful men is the fact that no matter how broad their scope of exposure somehow, deep down they always believe in the superiority of their native wisdom. Alexander was no exception, and so, he ordered the establishment of a city here. Now that the confluence has flowed southward to Mithan Kot, Uch Shareef still lives by the courtesy of royal decree. Few wisdoms can prove themselves superior through time.

Initially, the cities founded by Alexander connected with each other on colonial bondage but gradually, local interactions assisted in their expansions. In the times of Raja Chach, when the northern mountains were connected to the ports of the south, the maintenance of order implied defenses but the city did not take up a suspicious posture until the threat from the Mongols matured.

A few decades later, Muhammad Bin Qasim brought the sword of Hajjaj Bin Yousuf sheathed in religion. Initially, the city put up a tough resistance but the seven day siege paved the way for a conversion to Islam. With every coming year, faith bound the Indus region but the division of belief disintegrated the Middle East. Occasionally, scholars and the clergy tortured and persecuted by rulers of Bano Umayya and Bano Abbas flocked to Uch Shareef and made it their home. Within a millennium, the locality founded by herders was a city famous for its saints.

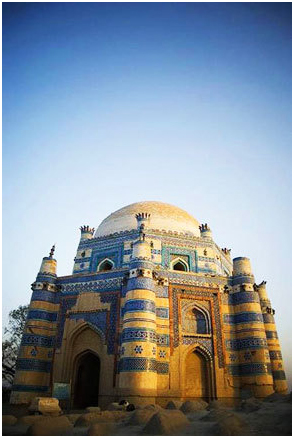

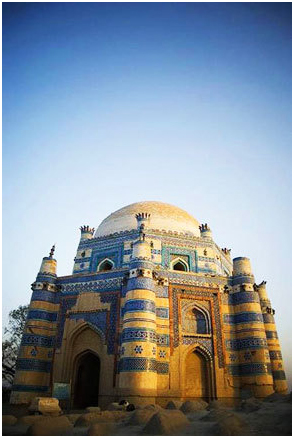

With its eventful history, Uch Shareef reminds one of the post card with a colourful picture on the front and black and white writing at the back. The vivid picture on the front is of multicoloured threads, heavy with prayers and tied to the trees in a courtyard where lie five graves, the resting places of Jalaluddin Surkh Posh, Jahanian Jahan-Gasht, Mayee Javinda, Abdul-Aleem and the architect, Ustad Nooriya. The double tone writing, at the back, is of sadness that drips from the rustic bricks, collapsing domes and fading signs.

Prayers tied up in threads, Uch Sharif. -Photo by Madeeha Syed

Interestingly, the colours of satiation, separation and unification are the same on both sides.

Between Ahmed Pur East and Liaqat Pur, the rail halts at Chani Goth, a century old railway station that has managed to contain countless stories in the hollows of its domes. Of these graves, the oldest, belongs to Jalal ud Din Surkh Posh.

This 14th century father-saint of South Punjab was once the citizen of Bukhara, until he decided to move on. Following the prophetic tradition, he left his Central Asian homeland and settled in Bhakkar. Soon after he had chosen this place as his home, the Soomro, Sayyal and Samma of the area opted for Islam as their religion and mapped the new geography of faith. They settled in areas like Kashmir, Bhanbhore, Jhang and went on to establish the town of JalalPur.

Today, a few of his followers run the meditation houses in Thatta, while others have established spiritual centres in Brussels. Through the long-winding traditions of Pir Pehlwan Shah of Kurram Agency to Shah Jamal of Lahore, the disciples of Jalal ud Din Surkh Posh are strongly committed to Sufi Islam.

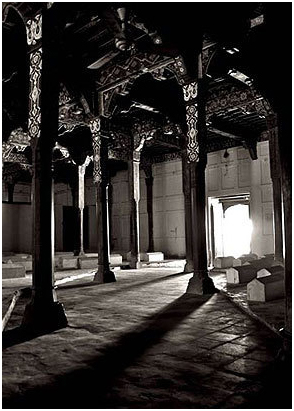

As mystics carry the cross for humanity, the colourful wooden columns at the tomb bear the burden of its heavily decorated roof. Every morning, the sun ray enters the building, takes on rainbow colours and captivates the devotees.

The ambience inside the tomb reflects the brilliance of architecture and dawns up on every visitor in a different shade. It is, by these graves, that one learns how need curates the believers and belief castes differing images of reality, all through the prism, called faith.

Around the grave of Jalal ud Din Surkh Posh, his kinsmen are buried in a manner which is organized yet divine.

Lined up with the adjacent wall, are the residential quarters, where visiting sufis stayed during their quest for the 'ultimate truth'. One of the residents was Bulleh Shah, who had a relatively long stay.

In the periphery of the mausoleum, the footprint of Hazrat Ali continues to attract the visitors. This revered artefact was brought in the 13th Century and is to date famous for its miraculous powers. The fresh petals and dull confetti, scattered around the venerated cast, translates into the age old conundrum of new wants and spent-out desires.

The outer walls of the tombs are painted blue, a typical color scheme of South Punjab that foretells Sindhi influence, and the frescoed ceiling inside is the signature of Abbasid architecture. Defying the summer sun that scorches the earth, the serenity of serving the mankind keeps the necropolis of these Bukhara immigrants calm and tranquil.

The second tomb belongs to Jahaniyan Jahan-Gasht, the world-wanderer. Translating to literally and literary sense of the world, this traveller`s identity included 36 pilgrimage trips that he marched to Mecca.

It was during one of these journeys when he came across Lal Deedi in Kashmir. Deedi was a saint in pursuit of spirituality. Some historians believe that Lal Deedi was a devout Hindu and others record that she had embraced Islam but no accurate account is found in this regard. She was lucky to have lived in an age when religious self had not seeped into social behaviours and faith was hardly an identity.

Despite her belief, Lal Deedi is regarded as one of the greatest mystics from Kashmir.

The tomb of Bibi Jawindi at Uch Sharif. -Photo by Humayun M.

After Jahanian Jahan-gasht, she met Sheikh Hamdan and is said to have nursed and tutored young Nur ud Din Wali. To date, her verses (Vaakh) are part of Kashmiri folklore and local wisdom. Birds of the feather, probably, have flocked together since long. From the colour scheme all the way to the overall ambience, the tomb of Jahanian Jahan-Gasht, is in many aspects, a close look alike of the tomb of Jalal ud Din Surkh Posh.

After the revered men, there is a series of three tombs. First one in line is the mausoleum of Bibi Jawindi, the grand-daughter of Jahanian Jahan-Gasht and an acknowledged saint of her time. Her divine reputation transcended Indian borders and as a token of devotion from Persia, the cost of her tomb was borne by an Iranian prince.

The second tomb belongs to Ustad Abdul Aleem, the teacher of Jahanian Jahan-Gasht and the third houses Ustad Nooria, the architect who designed and built all these tombs, lending them their share of eternity.

The tombs at Uch Sharif are a meaningful manifestation of an age long gone.

While half of its structure has caved in, the other half derives strength from its glorious past and stands, in dignity. Besides being a rare fusion of splendour and destruction, these monuments also symbolize the nature of Rohi populace, who won’t abandon the engaging charm in their tone, despite the adversity that surrounds them.

Partly the decay of these shrines is attributable to time and partly it was God-sent. According to an old keeper, the structures have been adversely affected by recurrent floods; most devastating was the one in last century. Wrath of past monsoons can easily be traced by marks left by flood levels. The tomb compound of Uch Sharif is a desert, in essence, and the surroundings carry the feel of the forest brought up by colonization canals. The contrast ensures the spiritual vastness of the shrine does not escape and the man-made soothe of jungle does not intrude.

Every day, the place is filled by the hustle and bustle particular to pilgrims. Devotees show up with their load of expectations, gratitude and despair and end up tying them with the branches of leafy trees, resting against the walls and prostrating on the hot tiled floors. The crumbling bricks and the fading shadows await the miracles which just do not happen. Strangely, the conviction which marked the life of the saint, buried inside, is totally missing from the lives of all those who frequent his tomb.

Like most places that thrive on religious faith, this is all that makes up most of the Uch Sharif.

Before partition, the Urs at each Sharif was one of the most happening events of the area. It featured a fair that was attended by Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims alike. Post partition, the attendance was reduced to Muslims and off late, it is left to Barelvis alone.

The sleepy towns of Fazil Pur and Rajan Pur lie up for Kashmore and exist indifferently around the convergence of rivers. On the other side, the railway station of Feroza precedes the contented town of Khanpur Katora. At some point in its history, Khanpur was famous for its pottery but its recent claim to fame is the sweet, Khoya. The train, then heads to Rahim Yar Khan and the road leads to mysticism. In between, a track leads to Bagh o Bahar, where an unknown village had a forest, full of memories, irrigated by RD-60, a rather memorable distributary.

Before it shunts away from the river, the train halts at Rajan Pur for paying homage to a seven-language epic buried in neighboring Chachran Sharif. The polyglot, Khwaja Ghulam Fareed, was born in Chachran but is buried in Mithan Kot. Having spent most of his childhood, without parents, his verses speak of the calm of a mother and concern of a father.

When the sun sets on Chachran Sharif, and local musicians guide and track their instruments, the humming tune of Mendha Ishq Vee`n Tuu hangs heavy in the air. Far and away in Kot Addu, something stirs by Pathanay Khan's grave, probably the memory of the voice that was as sad as a train that whistled away through December morning.

Mendha Sanwal Mithra Sham Salona,

Man Mohan Jana`n Vee`n Tu

Mendha Mulk Maleer Tay Maroo Thalrda,

Rohi, Cholsitan Vee`n Tu

Jay Yaar Fareed Qabool Karay

Sarkar Vee`n Tu, Sultan Vee`n Tu

Curtsey:DAWNN.COM: PUBLISHED JUN 30, 2014 10

The legend of Rohi

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

Derawar Fort, Cholistan Desert.

After Bahawalpur, the train shunts for Samma Satta. Like most good things, this centurion railway station is said to have been closed since July 2011. Moving past this now silent junction, the rail sounds its trademarks whistle across the wilderness of Rohi, echoing through the vastness reaching far and away.

The Nawabs were wise about developing another city, Dera Nawab Saheb, in the vicinity of Ahmed Pur East. The tasteful Abbasids, rightly credited for embellishing this part of Punjab, had developed beautiful cities for the public and elegant palaces for personal residences. The Sadiq Garh Palace is one of the series. Away from the flurry of the state capital, Bahawalpur, this residency had a mosque, as well as a cinema. It was built to house royal paraphernalia, and function as a camp office. The palace, more than a century old now, had 99 rooms, just one short of a hundred. Staying short of perfection was a lesson, the Abbasids learnt from Noor Mehal. Besides being home to the royal families, it also housed memoirs of dignitaries, the likes of the Shah of Iran, Prime Minister, Viceroy and the Field Marshals.

However, the year 1947 took away much of the grace of the princely states. As times changed, Ahmedpur East too developed a new outlook but Sadiq Garh chose to dwell in its past. In the chaos that saw the departure of regality, the large family of the Nawabs started telling the tale. Feuds for inheritance exceeded a receding estate. At last, there came a day when the residents abandoned the palace. Ironically, the building that once extended jurisdiction over Bahawalpur was now closed over sub judice. The large palace has decayed into an enormous vestige. It’s violated boundary walls and unkempt lawns are a sight of sorrow. The chandeliers are gone but the signature of majesty is still writ large on the empty hooks. The chess-patterned floor has lost its shine in rooms, where the wind enters and leaves through broken panes, unchecked. The frequent dust storms cover and uncover the city intermittently as memory jogs back to the story of the other sleeping beauty.

As this sleeping palace exists in the vicinity of a city wide awake, the towns of Liaqatpur, Feroza and Khanpur Katora, breathe in the proximity of a desert that lies still. On one side, the sand slips coolly into the sight and on the other, the greenery soothes the heart. A mustard field brings forth the desert and the sand dunes baptise the vegetation. In between, a silent agreement in the form of a small water channel runs calmly.

Right from this point, the magic of Cholistan starts taking over. Its name is derived from the Turkish word chol, which literally means sand. This sea of sand has some flashing islands of sand dunes, known locally as tibbas. Matching the destiny of an explorer, these dunes change their place and shift their location but never alter their temperament. If it rains, the earth is hardened and before turning white, it stays green for a little while. The drying pool of water can also be spotted, provided the under-ground water tanks built by Arab Sheikhs are not in close vicinity. With this magical metamorphosis, it is given an equally mysterious name “dhaar”.

Experiencing the strange life of the Cholistan nomads is subject to an obsession with the wild spirit of hitchhiking. While it envelopes the stranger with mystifying silence, the sand grains continue to whisper the secrets of survival into the ears of native residents, telling them to be more patient for the rains. From the AC coupe of the train, to the magical realm of a dhaar, this is all set like an opera of thrill, bliss and feral.

The tracks emanating from the main road cast a strange scene. Dripping with extended hours of stay, the residents file in their cattle and then herd them towards the desert. These cattle not only graze without a shepherd but also turn back from a certain point, without caution. God alone knows the rope they hold tight to; for neither do they distract nor disappear. These cattle follow an almost divine tradition of the one of the salah and continue grazing with only propriety brandished on their bodies.

These branding shepherds, ordinary owners and landlords who have long given up on a sense of inferiority or superiority, distribute the grazing areas amongst each other where they dig wells for sweet water. Having lived through 58 dry monsoons, Ashraf is a shepherd who owned the cattle counting upto 3000 heads. He did not know the exact rakats of the Isha prayer but stopped every passerby to offer them water. His grandfather had mastered the craft of foretelling the location of sweet water, partly due to his knowledge of metals and partly, his common sense. Based on his instinct, a party of six men, equipped with shovels and a ton of lime took six days to dig a well. The seasoned of them all, dug the earth and the skilled of them all, applied the lime, while the other four collected the earth and evenly spread it out nearby. After every 10 hands, they expanded the hole by half a hand and as they touched the water, the hole gradually took the shape of a well. Ashraf did not remember how they treated the lime to get the desired effect of cement.

If rains abandon Cholistan, the dhaars dry up like parched lips. The dunes symbolise barrenness and with every breath, the vastness of the desert sinks in. The entire desert is reminiscent of an Arafat, filled with imposing silence and the calmness of the final Day of Judgment.

The interspersed skeletons of animals died during quest for water, and intermittently grown shrubs are telling of a prayer that rose up to the sky but returned unsanctioned.

As the evening falls, the silhouette of small caravans can be traced in the far distances. Their convoys sink in and out of sand dunes and hark back the curse of Sassi and Sehti to the camel hoarder. The sacred silence of the desert and its consecrated winds prompt an inspiration in responsive souls, but transposing the desolate desert into the bustling cities, merely by melodies, remained the sole strength of Reshma…

The tales of Rohi and the travels of the camel hoarders are yet to unfold.

Kori Wala Dhaar

12 April 2002

As our jeep disappeared into dunes of Fareed’s Rohi, the sun also set into the folds of earth. The journey that started this morning from Sola Khoi had ended at Kori Wala Dhaar, after a brief stopover at Giglaan Wala Toba. Like me, a pair of desert sparrows has also chosen the lone tree in this Dhaar to spend the night.

Life in the desert has disciplines of its own and does not take much to adapt. The magnanimity of the local heart and it’s yearn for simplicity is yet to be scathed by the current civilities of our urban world. Raised on brackish water and salted camel meat, the sturdy bodied shepherds and colorfully attired dusky women, converse in the lyrical local dialect – a rhythm that can only be comprehended in the desert.

Ages ago, when the human wish list extended from living under the sun and over the earth to caves and structures, these nomads were fascinated by the idea of a house. The conflict, however, was not over the household but the very gypsy nature of these wanderers. They loved their land yet never wanted to commit. The earth would never let them go and they would never build a house on it, so a makeshift home was developed. A hedge raised in a circle served as wall and weeds woven into a sheet formed the roof that stood on a pole. This one room house is called a Ghopa and is, considerably, a world in its own. The props like clothes hanging from the hooks, rations stacked up in booths and water-filled earthen pots buried in earth alongside a pile of memories, establish that someone has just left, while the lonely smell of sadness lingers. The colonies of these hutments amply suit the nature of these wayfarers.

Most of the water reservoirs in Cholistan are filled by the first rain. These initial monsoons serve the residents for almost weeks before the reservoirs dry up. The residents, then, move to some other water sources, leaving behind the memory infested Ghopas, destined for a yearning wait. Despite the meager water availability, they do not forget to fill up a water pot and bury it in the Ghopa, for a thirsty traveler who might have lost his way.

Tired from constant travel under the sun, the rare sight of a Ghopa is no less than a miracle to dehydrated convoys. What is more human, than divine, is the fact that despite the parched lips and bodies drained due to thirst, the travelers still exercise selflessness. They enter the huts but leave the filled water pots for somebody more deserving; a phenomenon that keep the Ghopas water-ready.

Amidst these dunes, the oasis of Nawan Kot is situated at a crossroad of four sand highways. One track leaves for Bijnot, the other leads to the city and the other two navigate around local dunes and dhaars.

On one side of Nawan Kot, lies the centuries old Mughal fort. Located by the riverside, it was one of the series of forts built at Khan Garh, Islam Garh and Khair Garh. As time lapsed, all arches, elephant gates, tunnels and Mughal grandeur caved in while the boundaries, minarets and stories survived to tell the tale. On the other side, stands the mosque maintained by the Hobara Bustard hunters. Centered around a pond that sits at the crossroads of these sand highways, the oasis of Nawan Kot has the ability to transcend through the physical dimensions of time and space. Between the mosque and the fort, the water pond serves the cattle of Rohi, the soldiers of the Rangers, the residents of Rohi and the plants that compose the fabulous world of Cholistan.

The place is comparatively livelier because of the constant existence of water. The real beauty, however, is the immaculate trimming of the trees. The plants are so precisely manicured that the use of an accuracy instrument cannot be ruled out. At the outset, this phenomenon remains a mystery that is until the locals explain that the trimming is a result of the grazing cattle that eat the dropping leaves, maintaining the linear silhouette.

In this chowk-city of Nawan Kot, where Rangers and gypsies are always in transit, Haq Nawaz is the most permanent resident. Every morning, a vehicle from the Abu Zahbi Palace Office imports this cleric of the Nawan Kot mosque from the neighboring city. Haq Nawaz only returns after he has preached the message and has completed the long day’s journey, including five divine stopovers. Besides the meager palace office salary of Rs8,160, he also runs the lone grocery shop of Nawan Kot.

Despite his devout manner of ablution, Haq is far and away from the rigid dialectics of religiosity. His conversation is free from the vanity of serving his faith in a desert for the last 20 years. His deep set eyes, framed with Gandhi-glasses tell of a faith that was born out of redemption.

Though the cash box at the shop and the devotees at the mosque are mostly discouraging, Haq is persistent. The unseen devotion of this cleric-entrepreneur with his Lord closely resembles the invisible umbilical cord that ties the calf with its mother. Haq shows up to open the shop and the mosque, regardless of customers and the faithful.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM:Published JAN 27, 2014 and FEB 17, 2014

The Kot of Kamalia

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

The Aalif Laila of the wood remains untold. Sheherzad and Sheheryar, are themselves lost in time. Inside the city, one of the streets houses the last of the Pirjhas, Akhtar. He trains his apprentices in this art but their craft is restricted to the heavy furniture of dowry, a commodity that could never graduate to become an artifact, no matter how artistic.

As religion and culture fell to politics, khaddar resigned to the confines of Kamalia.

In one corner of the shop, sits a model of the Taj Mahal made by Pirjha. This wooden replica is probably the closest any artist could get to the real wonder and can qualify as a resting place for any Mumtaz Mahal.

In another corner, Pirjha has placed the recently filled admission forms. His son Anas Ali is set to join an engineering college in RawalPindi to study Mechatronics. Pirjha believes that instead of excelling in ancestral craft, his son should graduate from a universal faculty. Pirjhah silently mourns the death of a heritage, while the city lies indifferent to the fallen jharokas of Gulzar Mahal.

From Chiniot, the rail moves to a desolated station. Almost 40 years ago, this station saw a small feud which eventually grew into a persecution; the honest account of which is neither told in public nor written in history. The place is Rabwah. Those who named the city, had a verse of the Quran in mind and those who desecrated graves, had the constitution to uphold. Nobody, however, recalled that somewhere in 1944 at Sri Nagar, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had something to say about it.

The road that links Sargodha with Chiniot cuts Rabwah in two halves. On one side, is the graveyard which is almost mythical for the children in the neighbourhood and on the other side, is the deserted city. The names of various settlements are reminders of medieval boroughs but the derelict appearance defies those. The opulent houses look neither vacant nor lived in. A day of wandering in the city registers only handful of faces. This state of the city is attributed to both, the devotion and hatred that stems from religion. Till time tells who is on the right side of faith, the city will, probably continue to live in this desertion.

Rabwah, Chenab Nagar or Chak Digian (whatever the constitutional committees chose to call it) gives way to Lalian, a city that claims political descendants from Tipu Sultan, and a police station from the year 1867.

Subsequently comes Dhoop Sari, now known as Sargodha. The city is a candy store of stories but the deserts of the South strike the same chord as that of the peacock that craves to be seen. Going any further is not an option.

After Jaranwala, the train halts at Tandlianwala. There in one of the graveyards, rests Naz Khialvi, in eternal peace. The legendary lyricist’s claim to fame was Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s "Tum ik Gorakh Dhandha ho". The train whistles past Rehmay Shah and then halts at Kanjwani, a town famous for its mela. The fair, which was once a Baloch nomadic tradition, is now a Punjabi celebration.

Almost all participants bring a human dimension in to their relationship with their cattle. There are oxen that have been raised as sons and horses with phenomenal lineages. Often, the roosters and quails raised for the show, take precedence over blood relations. But, of late, the politics of democracy and dictatorship have made their ingress in these dimension as well. The Balochs, Jats and Syeds who once rode the wild stallions together are now more aligned on caste lines.

Staying away from the waters of Chenab and drawing close to the mystery of Ravi, the train reaches the Kot of Kamalia.

A dense jungle by the river was all that could be said about Kamalia centuries ago. On the river bank, Khokhar boatmen had established their settlements. Apparently peaceful, the Khokhars had what it took to defend their land, so when Alexander attacked them, they gave him tough battle. The account of this battle is not mentioned anywhere specifically, except for a hint of the glorious resolve here and there; the fact that remains, however, is that Alexander now finds a mention in the history of Kamalia.

After almost a millennium, Raja Sircup ruled the area. Known for his brutality, he played polo with heads at stake. The notorious Raja manipulated easily to see the opponent lose his head, a trophy he would decorate on the walls of his fort. That was until he came across Raja Rasaloo, the son of Raja Saalbhan of Sialkot.

Despite his manipulation, Rasaloo won the game and had Sircup’s head and as a matter of ritual, his daughter, Rani Kaukalaa. Rasaloo, in this folk lore, appears to be an adventurous spirit who spent his time hunting and building palaces near game grounds. Dhoosar was one such palace, where Rasaloo had housed Kaukalaa, when the Raja of Attock, Bikram saw her. The two met accidently, but fell in love instantly. Before the romance could prosper, Rasaloo became aware of it. He had Bikram killed in the woods and sent Kaukalaa, the kebabs made up from his meat. Devastated, the queen jumped out off her window to her death.

The present name of Kamalia is derived from the Kharal chief, Kamal Khan. In the early years of the 14th century, Kamal Khan met Rai Hamand Khan, the Kharal ruler of this land, then known as Hindal Nagri. The latter introduced him to Shah Hussain, the saint. Kamal Khan presented a khaddar khais to Shah Hussain, who reciprocated by foretelling him as the ruler of the jungle. Months later, Ibrahim Lodhi replaced Hamand Khan by Kamal Kharal. The new state founded by the Kharals at the site of Sircup’s city is now known as Kamalia.

During the war of independence in 1857, the city remained, with the freedom fighters for almost a week. After the war was over, trade through the rail added to the development of the city. The atrocities of the Raja and the injustice of the Raj would have prevailed in public memory for longer had the country not had its chance with democracy and dictatorship, both of which overcast the tyrannies.

Now famous for its khaddar, the city is as introverted as the spinning wheel. At the dawn of the last century, Khaddar became the insignia of the "Saudeshi" movement (all things local) and subsequently, the emblem of the "Swaraj". The coarse cloth defined nationalism and the spinning wheel symbolised tradition, where a mother explains the ups and downs of life to her daughter while they spin. As religion and culture fell to politics, khaddar resigned to the confines of Kamalia.

When the two countries gained independence, khaddar also bore the fruit of a free economy. It has graduated from the spinning wheel to shuttle-less, power looms. Brand names like khaadi on this side and fashion phenomenon like In Sync on the other have brought new realities to khaddar. This insignia of the nationalist movement is now a feature at international shopping malls.

Next up is Pir Mahal, a city established in the memory of Pir Qutub Ali Shah. When the Pir wanted to build a house, his devotees obliged. They baked each brick themselves to construct the palace. The city was properly planned after the arrival of the municipality. With a block each allotted to Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs and named Masjid block, Mandir block and Gurudwara block, respectively.

The Masjid block has retained its name, while the other two blocks have been renamed to Makkah block and Madina block.

Throughout this journey, the stories from the other side of Ravi remain untold.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM:PUBLISHED SEP 16, 2013

The Alexander of Samundri

MUHAMMAD HASSAN MIRAJ

Sadhar, initially, stood away from the city, distant and disconnected, but as the population exploded, it fell into city precincts. The Sardars who migrated from Sadhar never let it go completely and it now qualifies as a Sikh sub-caste. Leaving Lyallpur and by passing Samanabad, the train halts at Sar Shameer.

A bricked house in the village stands as fresh as an early morning dream. It has been 10 years now but the image of a grey hand pump watering the paved courtyard is etched afresh in memory. The cemented walls of the house perpetually radiate the sadness of impending departure. While a father returns after completing his service, his son goes back to safeguard the land. Once a warrant officer and now a farmer, the silence of this father spoke of his inner conflict. Caught between the pride in his son’s military career and his own failure in passing on the love for his land, a mix of the feelings prevailed, though the orphaned grains sided with the melancholic father.