|

The Punjabi contribution to cinema-1

Ishtiaq Ahmed

In the first part of this series, Ishtiaq Ahmed explores themes in Punjab’s history which shaped its music, popular consciousness and cinema

Baba Guru Nanak contributed greatly to an ethos of pluralism in Punjab

For us middle-class fellows who grew up in Lahore in the 1950s and 1960s, the greatest joy and entertainment was to save enough pocket-money to go and watch a film in one of Lahore’s film theatres. In fact whenever I left home on Temple Road and reached Regal Cinema or Plaza Cinema, the pulse would start accelerating – in both these theatres Hollywood and British films were shown. As soon as one crossed the Mall and reached McLeod Road via Regal Chowk or Abbot Road via Charring Cross, with the exception of Odeon Cinema, all others – Regent, Ritz, Kaiser, Palace, Rattan, Sanober, Nishat and Capitol – showed Bollywood and Lollywood films. Further away near the Lahore Railway station was Rivoli. There were several outside Bhaati Gate and then Crown Cinema cropped up in Garri Shahu. Some new ones were added to Abbot Road as it moved towards the Shimla Pahari. More still were built, one close to Gulberg Main Market and another on Ferozepur Road. These were later additions and now after 42 years, sitting here in my apartment in Solna, Greater Stockholm, I can’t recall their names. I am told that memories from early childhood remain etched forever while those of a later period tend to dim or fade away. This is really true when I try to remember the names of the cinemas of Lahore. For Indian readers with a Lahore connection, some theatres I have mentioned bore a different name.

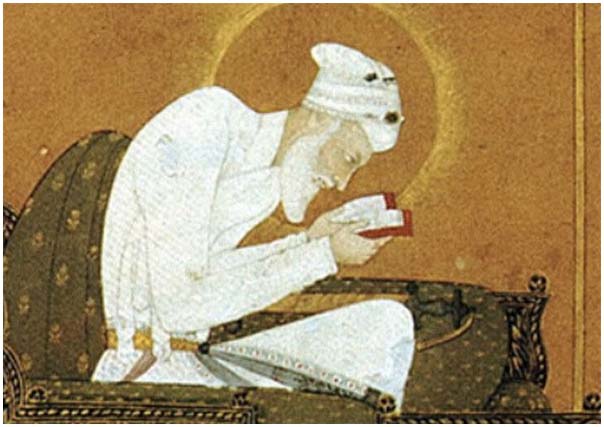

Punjabi actor Prithviraj Kapoor thought film theatres were akin to temples and mosques

I remember once as a teenager when I was infatuated with a girl in our neighbourhood, I did not do so well in my exams. My father wrote a nasty letter to my mother, who lived in Karachi (my parents divorced in 1950 when I was only three and that scar has never really healed) blaming my bad results for listening to Radio Ceylon incessantly instead of doing my homework. Like most Punjabis, he looked down upon music and musicians though he would go into a trance when attending qawwali (sufi music) sessions. That made me wonder about the distinction he drew between permissible and impermissible forms of music. Plato’s distinction between music which elevates the soul and that which excites it to temptation is the cornerstone of the puritanical mindset. The Greek philosopher wanted to create an ideal, perfect state and in order to create ideal citizens he prescribed censorship to weed out influences which excite the senses. Islamic orthodoxy is solidly founded on such a distinction. I am, of course, thinking of orthodoxy in the Barelvi tradition because Deobandis and Wahhabis consider all music haram – even qawwali – although even they appreciate the azan (call to prayers) being recited melodiously. Quite simply, the universality of music cannot be denied completely.

Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, whose orthodox religious views were opposed to music and dance

The great Punjabi veteran actor Prithviraj Kapoor once in the early 1960s told a gathering of Indians and Pakistanis in London that film theatres were akin to temples and mosques, because they too received faithful members regularly. I think that was a very incisive remark indeed. Films, like religious and secular authorities, shape ideas and ideals and convey some social and moral message. That is why the religious and secular establishments are always wary of the influence of the cinema. Censorship operates in all societies and there have been periods when cinema has been reduced to sheer propaganda as was the case in Nazi Germany and even the Soviet Union. Even the liberal United States has had its dark McCarthy era (1949-1959), when alleged Communists working in the film and entertainment industries were hounded and victimised.

During the British epoch, when films emerged as a brand new type of entertainment in the Subcontinent, colonial authorities ensured that Indian cinema did not address themes related to the ongoing freedom struggle. On the other hand, mythological and pre-colonial historical epics were permitted. On the whole, pre-Partition Indian cinema catered to the boy-meets-girl theme, which is a universal subject. We are an emotional people who adore film heroes and heroines. Additionally Urdu and Hindi poetry thrives on tragedy and that means songs are central to convey joy and pathos attendant upon the vicissitudes that the lovers have to go through before they are united – or even more tragically separated. I consider the Subcontinent’s cinema an indivisible manifestation of popular culture and entertainment, which has over time evolved in different forms because of a combination of political and economic variables. Some of the most gifted writers and poets – many of whom were part of the progressive movement while others were great romantics – joined the film industry to make a living. It had a very benign influence on the culture that evolved in the industry. Thus from the very beginning cinema became a vehicle for inter-communal amity and understanding. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Jews and Parsees became part of an integrated – or rather an assimilated – pluralist community and cultural ethos.

Prithviraj Kapoor compared cinema to houses of worship

However, all film industries have to conform to the national project even when they enjoy autonomy. Therefore, despite an inclusive, pluralist and secular ethos the compulsions of state-nationalism have impinged upon the cinema. Whenever India and Pakistan are drawn towards conflict or actual hostilities break out, narrow nationalist and jingoistic themes are taken up in films. Mercifully such deviations remain aberrations which represent reactive responses to perceived threats. Soon afterwards, things return to normality and the film fraternity returns to probing the eternal problems of love requited and unrequited. Of course cinema has also addressed serious social issues and promoted enlightened attitudes and solutions.

In this regard, it is important to take note of the extraordinary contributions of the Punjabis and Bengalis to the Bombay film industry – now known popularly as Bollywood – which before Partition (1947) had established itself as the epicentre and capital of the film industry. Perhaps, the fact that both provinces were blessed with major rivers whose tributaries facilitated brisk trade and movement, a varied background of shifting scenery and fleeting communities stimulated the artistic impulse of the people. Who would deny that the Danube has served as the backdrop against which great music has been created in eastern and central Europe? The same is true of the Nile and the Volga. Even the Ganga-Jamuna valley is famous for its romance and poetry. In the case of the Punjab, there is the additional charm and romance of its southern and western deserts where the music is haunting and Reshma’s voice is a good example of that. One can, in a broad sense, assert that songs and music flourish in environments which are not static and monotonous.

Colonial authorities preferred cinema based on mythology and pre-colonial history

My idea of the Punjab is an expansive and inclusive one and includes Punjabi-speakers settled in Peshawar and Bannu-Kohat, Quetta and other such places – including Delhi in the east. Pre-colonial and colonial Punjab was the stronghold of a vibrant tradition of story-telling and melodic rendering of heroic and romantic tales. Thus epics such as Heer Ranjha, Sohni Mahiwal, Sassi Punnu, Puran Bhagat were recited in the baithaks[private sittings] and at deras (more public sittings held by prominent, powerful people) or in the village square under a tall and big tree. Professional story tellers would wander around the Punjab narrating tales from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, the tragedy of Karbala as well as the Dastan-e-Amir Hamza and many other such stories. On the occasion of Ram Lilla, wandering actors would perform to eager audiences. Equally, mehfil-e-samma (Sufi music sessions) in the form of qawaali and other collective meditative practices at sufi shrines attracted communally mixed audiences.

Shah Hussain, a rebel sufi, drank wine and danced ecstatically in the streets of Lahore. His idiosyncratic behaviour and defiant life style earned him the ire of the conservative sections of society, who approached Emperor Akbar – in those days he was based in Lahore – to chastise him because of his close association with Madho Lal, a beautiful Brahmin boy from Shahdara, just across the Ravi on its western bank. Akbar ignored their protests. Shah Hussain and Madho are buried under the same tomb and an annual festival attracts a large number of people. Later, Bulleh Shah – another rebel sufi and poet par excellence – migrated from nearby Kasur and lived in Lahore where he, too, gathered a large following of non-conformists. He and his sufi master Shah Inayat Qadri belonged to the Qadri-Shattari Order which sought a synthesis between Islamic and Hindu mysticism and emphasized the unitary nature of human existence, known as the doctrine of Wahdat-ul-Wajud.

If we now bring into the picture the influences of the Yogi and Bhakti movements and add the even greater influence of Baba Guru Nanak, who had a Muslim musician Bhai Mardana always accompanying him wherever he went preaching his message of a shared brotherhood (Nanak Dukhia Sabb Sansaar), we can broaden the base of the multifarious influences which softened the rigours of war and conflict endemic to the Punjab since it was always caught up in the military conflicts between Kabul and Delhi-Agra. One can argue that the Punjab was culturally an unorthodox region where both strict and rigid Hinduism and Islam could not hold sway for long and the Sufi-Yogi-Bhakti-Guru tradition represented the popular wisdom of ‘live and let live’.

Balwant Rai Theatre (Rattan Cinema) in Lahore during the 1940s

The rise of Aurangzeb and religious orthodoxy was a setback to such traditions and my theory is that his ban on music probably drove the Muslim musicians of Punjab and elsewhere towards the Shia faith, because originally when they converted to Islam from Hindu stock they were mostly patronised by the Sufis who adhered to inclusive doctrines nominally subscribing to Sunni principles. This is , of course, an issue which requires further research. A branch of them remained Sunnis and became qawwalisingers. The harm done by Aurangzeb’s puritanism, however, was not necessarily so profound. During the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1799-1839), court patronage to artistes was again restored and Lahore had a thriving courtesan culture. In fact the Maharaja’s indulgent court life included regular visits to the courtesan quarters. It proved to be a boost to music and dance; and even skits and drama. Following the death of Ranjit Singh, the Kingdom of Lahore disintegrated quickly and the British annexed the Punjab militarily in March 1846.

The era for films and cinema was still some time in the future but the rudiments for it emerging in the Punjab had been laid by a vibrant culture of music, dance and popular theatre forms.

Curtsey: The Friday Times: Jan 8, 2016

The Punjabi contribution to cinema – II

By Ishtiaq Ahmed

Ihtiaq Ahmed continues his discussion of the historical and cultural context in which Punjabis participated in the film industry s

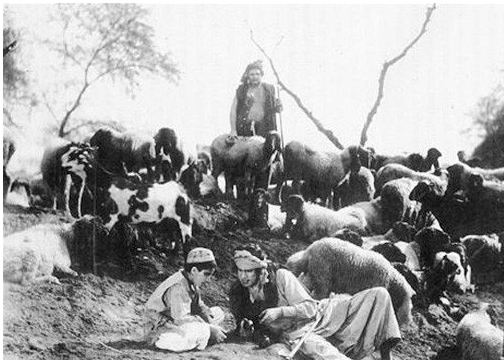

A still from 'Gudaria Sultan' (A R Kardar, 1930) - photo courtesy Farooq Sulehria

Pre-Partition Bombay became the capital of the Indian film industry. How do we explain the very large Punjabi presence in its evolution from the outset? I think a number of fortuitous developments converged to give the Punjabis an advantage in faraway Maharashtra over many other nationalities who did not speak Urdu/Hindi. The British favoured the recruitment of Punjabis in their Indian Army but they preferred Urdu instead of Punjabi as the medium of instruction in the government and municipal schools they established. Amongst the East India Company policy-makers in India, some favoured Punjabi while others preferred Urdu, which was already in use at the lower level in the civil and military sectors in northern India. The latter school of thought favouring Urdu prevailed. It was argued that Punjabi and Urdu were kin as languages. Therefore Urdu could serve as the connecting language for the expanding British Empire and thus help disseminate communications and streamline standardisation more efficiently; and thus integrate the various branches of government. The British established the Urdu Board in Lahore and not Delhi or Lucknow and people like Muhammad Hussain Azad and later even Syed Imtiaz Ali Taj left UP and Delhi respectively to promote Urdu in the Punjab. Punjab’s importance for the British was of course its location on the route to central Asia and therefore the success of the Great Game against Russia required that Punjab should be firmly co-opted into the imperial scheme of things.

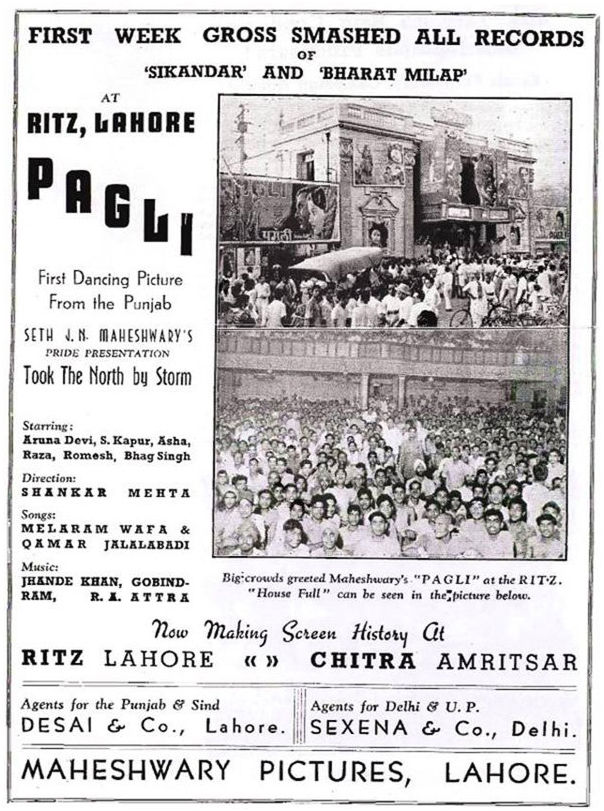

A poster from the Ritz cinema in Lahore

Irrespective of whether this was some grand conspiracy against Punjabis as some Punjabi nationalists would like us to believe or simply a practical approach to maintain coherence in the state machinery, the result of such a policy was that educated Punjabi Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians were almost invariably literate in Urdu. On the other hand Punjabis, serving in the army and other tertiary institutions, were posted to far-flung regions of India. As is usually the case, service-sector people and small businesses also move along in such circumstances and that is how Punjabi colonies began to be established in Bombay, Calcutta, the industrial town of Kanpur and of course in Delhi. Hindustani (spoken Urdu and Hindi become Hindustani) became the lingua franca of the lower tiers of the British colonial order and even illiterate Punjabis could manage to use it wherever they went in search of a livelihood.

Understandably the urban centres which evolved under British patronage became the engines of change and transformation where modern cultural values became part of the social and intellectual milieu. Madras, Calcutta and Bombay blossomed as dynamic urban centres. While Calcutta served as the first administrative capital of British India, Bombay became the financial capital. Film production started initially in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. Delhi became the colonial capital in 1911 and British grandeur added to its majesty, already embodied in the Mughal and earlier monuments of the city. The last great contribution to modern city-building from the British was generously reserved for Lahore. It became the premier city of northwest India. Schools and liberal arts flourished. Science and medical colleges and even a university (The University of the Punjab was established in Lahore in 1882) set up by the government and community organisations helped produce people with modern ideas and ambitions. Moreover, overall prosperity increased by the beginning of the twentieth century because of the canal colonies and Punjab became the granary of the Subcontinent. Quite simply the Punjab became the darling province of the British. The princely families of the Punjab and many even beyond it built residences in Lahore. Additionally, Bengali teachers – Hindus and Christians – also flocked to Lahore and brought along their music and dance and other forms of performing arts. Not surprisingly, Lahore flourished as a paragon of progress and communal harmony although it was Hindus and Sikhs who took most advantage of the educational facilities and business opportunities while the Muslims lagged behind. Later, this factor was to play an important role in the partition process of 1947.

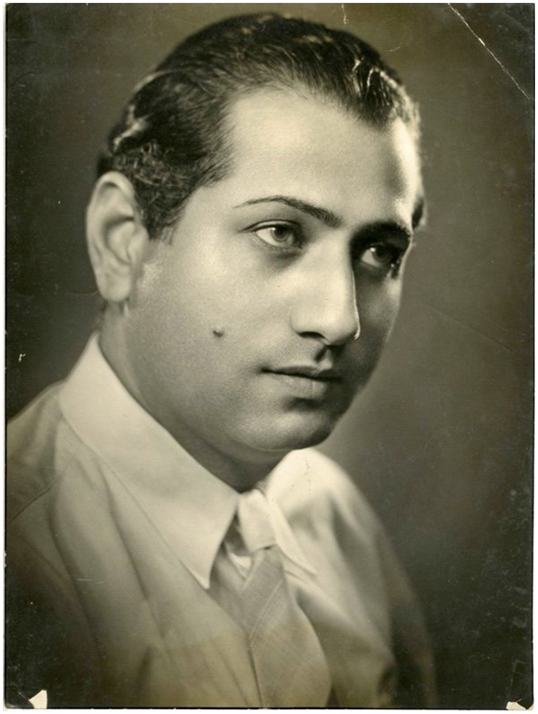

A.R. Kardar starred in the first silent film made in Lahore in 1924

By the early 1920s there were nine film theatres in Lahore

At any rate, by the early 1920s there were nine film theatres in Lahore. It was the era of silent films. The first silent film made in Lahore The Daughters of Today was produced by a former officer of the North-Western Railways, G K Mehta, who had imported a camera from London. It was released in 1924. The lead role was played by the future legendary Bombay filmmaker, Mian Abdur Rashid Kardar, famously known as A R Kardar, who also assisted Mehta as assistant director. The film was shot largely in the open air as there was no studio in Lahore at that time. Kardar and his fellow artist and calligraphist, M Ismail, later a noted character actor in post-partition Pakistani films, sold their properties and in 1928 established a studio on Ravi Road, near Bhaati Gate. They founded a film production company called United Players Corporation. The lighting facilities in the studios were not very good and shooting was possible only in the daylight. The choice of Ravi Road was partly dictated by the fact that a thick forest along the banks of the River Ravi and the mausoleums of Mughal Emperor Jahangir and his wife Nur Jahan across the bridge provided excellent locations for shooting action-packed melodramas.The first film produced at the Ravi Road Studios was Husn Ka Daku (1929). This time, Kardar was the director himself, as well as the leading male actor opposite Gulzar Begum. Ismail played a supporting role. An American actor, Iris Crawford, also acted in that film. The film did quite well, but Kardar decided not to act in films and instead concentrate on directing. Kardar also produced Sarfarosh (1930) with Gul Hameed playing the lead role. It was noticed in Bombay and Calcutta and Lahore began to receive greater attention. In those days, live orchestras provided background music as well as song and dance performances. Consequently, from the very beginning the musician community of the Punjab was associated with films and became an integral part of its evolution. The first Indian talkie Alam Ara, produced in Bombay, was released in 1931. It was a sensation. It had at least one Punjabi in the cast – Prithviraj Kapoor. Incidentally, Urdu was mentioned as the language of the film.

India’s first talkie, the film ‘Alam Ara’ met with great success in Lahore in 1931

Lahore in the 1940s was an important film-making city, but the money was in Bombay and Calcutta

Although Bombay, Calcutta and Madras emerged as centres of film-production earlier than Lahore, it enjoyed an advantage over Calcutta and Madras when the talkie era began. Calcutta was essentially the cultural capital of the Bengali renaissance while Madras catered for the Tamil-speaking audiences of southern India. On the other hand, Punjabis were conversant in Hindustani – the actual lingua franca of northern India. Urdu, written in the Persian script, and Hindi in Devanagari, when spoken by people in day to day life was simply Hindustani. On the other hand, Marathi- or Gujarati-speaking Bombay became the centre of Urdu-Hindi cinema. It also became the unrivalled film capital because it had the greatest outreach to filmgoers all over India. Therefore, Lahore or rather Punjab provided the Hindi-Urdu-speaking talent which could be absorbed easily at the Bombay film industry. As explained already, several structural changes wrought by the British had equipped the Punjabis with skills which they could market outside their province and language was one very important skill in this context. Therefore, several generations of Punjabi Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and even some Christians, often with a Lahore connection, sought a career in the Bombay film industry as actors, music-directors, lyricists, story- and script-writers and indeed as directors and producers.

Although A R Kardar moved to Calcutta in 1930, he continued to make films in Lahore as well. In 1932, he produced the first talkie from Lahore, Heer Ranjha. It was in Punjabi. Soon afterwards Lahore’s reputation as a filmmaking centre was established firmly when Roop Lal Shori, a resident of Brandreth Road, Lahore, began to produce films such as Qismat Ke Her Pher. Later, a Gujarati, D. M. Pancholi, set up a studio in Lahore. Himansu Rai, a Bengali, who later founded the famous Bombay Talkies in Bombay, also started his career in Lahore. Punjabis had begun to look for career opportunities in Calcutta and Bombay as well. Legendary KL Saigal, Prithviraj Kapoor, writer, song-writer and director Kidar Sharma and singer Mukhtar Begum – both from Amritsar – were based in Calcutta from the early 1930s.

Pran Nevile has extensively chronicled the early film industry of Lahore

The Lahore-born veteran chronicler and music patron Pran Nevile has vividly described the vibrant cinema culture that evolved in Lahore in his book, Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. People thronged to its various theatres in large numbers and visits by leading Bombay film stars became memorable social events. Among them was the visit on 2 December 1937 by legendary singer-actor K L Saigal, a Punjabi from Jammu/Jullundur, which attracted huge crowds. In the beginning, films produced in Lahore were mainly in the Punjabi language. Till 1947, Punjabi films were shown in the whole of undivided Punjab as well as in Delhi, Calcutta, Bombay and Kanpur where Punjabis had been settling in significant numbers since the early twentieth century. However, in the 1940s some very successful Urdu/Hindi films were also produced from Lahore. Among those were Khandaan (1942), Khazanchi (1941) and Dasi (1944).

In any event, although Lahore of the 1940s was emerging as an important film-making city, most of the money and capital was still in Bombay and Calcutta. Therefore besides the beautiful men and women of Punjab and indeed villains, character actors and comedians who tried to make their mark in those cities, Punjabis with other artistic and technical skills also sought a livelihood in them. In fact it was not uncommon that some artistes worked in all these cities and films were also shot on locations in these cities. In the forthcoming articles in this series we will review the contribution of the Punjabis to cinema in all these three cities but obviously the most space will be given to the Lahore-Mumbai connection. My conviction is that the cultural links between India and Pakistan are too deep to be severed completely by nationalist politics and concomitant tensions and armed conflicts which the 1947 partition of India, Punjab and Bengal has bequeathed to the Subcontinent. It is no exaggeration that Pakistani plays are watched eagerly by Indians and we Pakistanis love to see Bollywood films.

At some recent weddings which I attended in Lahore, the mehndi and wedding parties borrowed the latest songs and dances from Bollywood. Interestingly this is true of all classes and ideological groupings. At least at two such receptions where the families were demonstratively of Islamist leanings and wore their nationalism proudly on their shoulders, the young boys and girls who sang and danced remained oblivious to the fact they were influenced by Bollywood rather than the Jama’at-e-Islami headquarters at Mansura on the outskirts of Lahore. I am sure this tendency will remain unchanged in the future as well. There is nothing surprising about it. Language is a great connector and so are music and poetry. They emerge from the inner recesses of the historically formed and culturally-shaped human personality. So it comes as no surprise, that for instance, Heer Ranjha has been made and remade more in Bollywood than in Lollywood.

Ira Bhaskar and Richard Allen talk about the Islamicate Cultures of Bombay Cinema and demonstrate how Bombay cinema has a long history of probing themes that focus on the imprint of Islamic culture. So it works both ways. When former President Asif Ali Zardari said that in every Pakistani there was an Indian and in every Indian a Pakistani he probably made the wisest and most honest remark of his life. Of course he was assailed not only in Pakistan but also in India. I remember hysterical Hindu nationalists on social media expressing disgust at being reminded of a Pakistani dimension within them. So the politics of rejection is mutual, though in Pakistan it is more easily noticeable because the hegemonic Two-Nation Theory requires a denial of any such relationship. In the forthcoming articles in this series I will be demonstrating the very significant Punjabi contribution to cinema which I believe still plays a binding role in spite of ultra-nationalist encroachments on Bollywood and Lollywood.

Curtsey:The Friday Times:22 Jan 2016

The Punjabi Contribution to cinema-III

Ishtiaq Ahmed

Ishtiaq Ahmed chronicles the process by which artists and professionals of Punjabi birth established themselves in the Indian film industry

Beautiful Punjabi men and women headed towards Bombay and Calcutta because in the formative years, the Lahore film industry had limited capital and essentially produced Punjabi language films which had limited outreach. Villains, character actors, comedians, bit actors, story writers, script writers, song writers, music directors, directors, producers, filmmakers and studio owners from the Punjab – all those who sought employment opportunities and nurtured ambitions to make a name for themselves at the all-India level – headed towards Bombay and Calcutta. As mentioned earlier, the advantage they enjoyed over other nationalities from South Asia was their Urdu-Hindi (Hindustani) language skill. The competition they faced was from Urdu- and Hindi-speakers of northern India, Bihar and the princely state of Hyderabad in southern India. Veteran film journalists Pervaiz Rahi and Yasin Goreja have written excellent accounts of the history of Lahore cinema. Inevitably their books provide very interesting leads to the linkages between Lahore, Bombay and Calcutta.

Pervaiz Rahi’s book, Mian Abdur Rashid Kardar, sheds considerable light on the contribution of the giant of the film industry. Kardar belonged to the noted Arain clan ofzaildars with their traditional haveli in the Bhaati Gate area of Lahore. Kardar (1904–1989) married the heroine of his film Qatil Katar, Bahar Akhtar in 1930. Bahar Akthar was the elder sister of the more famous Sardar Akhtar, who distinguished herself playing a fisherwoman in Sohrab Modi’s classic Pukar (1939) which epitomises the Congress-inspired interpretation of history and is a eulogy to Emperor Jahangir’s high standards of justice.

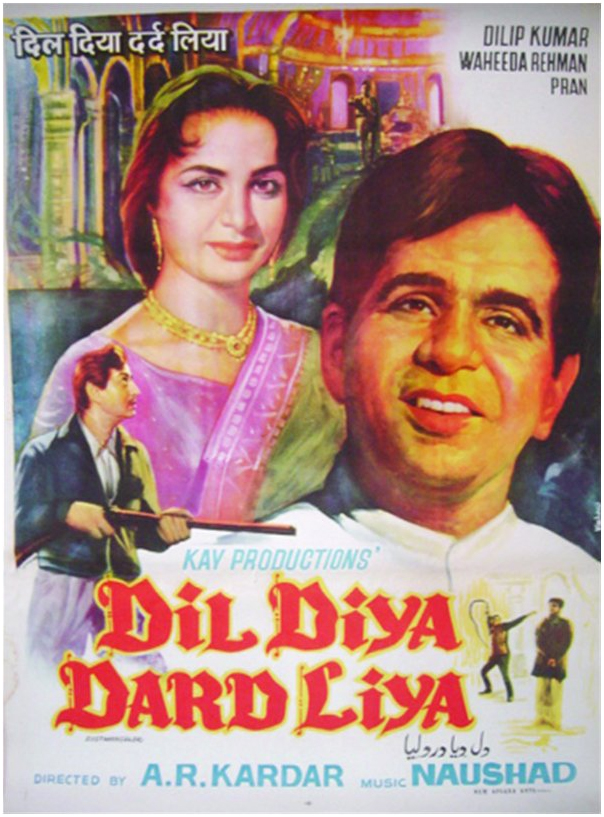

Poster for A. R. Kardar’s hit ‘Dil diya Dard liya’

Punjabis in the film industry competed with Urdu- and Hindi-speakers of northern India, Bihar and Hyderabad

It was Kardar’s second marriage. It caused consternation not only in his own family but that of Bahar Akhtar as well and he was dragged into a court case by her family but was acquitted after she told the court that she had willing married him. At any rate, the film was halted and the negatives burnt. Kardar left Lahore and joined the East India Film Company in Calcutta. He took with him his friends from Lahore: character actor M. Ismail and veteran heroes Nazir, Hiralal, Fazal Shah and Gul Hameed. Rahi has recently written a book, Agha Hashar Kashmiri aur Mukhtar Begum, on the famous singer and stage actress (and later film heroine) Mukhtar Begum (elder sister of Farida Khanum). Mukhtar Begum belonged to Amritsar and was married to Agha Hashar Kaashmiri, fondly remembered as the father of stage drama and as India’s Shakespeare. She played heroine in several films of East India Film Company and was instrumental in getting Kardar his job as a director. Kardar’s Aurat ka Pyaar was a super hit. However, the company collapsed and Kardar moved to Bombay, where he eventually established Kardar Studios. He went on to make some all-time popular films such as Shah Jahan in which the famed K. L. Saigal played his last role before his death in January 1947. Other outstanding films by Kardar were Dard (1947), Dulari (1949), Dillagi (1949) andDastan (1950), in which he collaborated with music director Naushad. Suraiya, Geeta Bali, Hiralal, Shyam, Suresh (Nasim Ahmad born in Qadian, Punjab) and singers Mohammad Rafi and Shamshad Begum – all from Lahore or with a Lahori connection – were part of his team. He also relied on Lata Mangeshkar and later worked with music director C. Ramchandra. Talat Mahmood sang for him too.

Kardar’s aura as a director did not last, however. He eventually faded into oblivion, more or less. His last noted film was Dil Diya Dard Liya (1966). Dilip Kumar acted in it. On the whole, Kardar’s presence in Bombay helped to establish a large Lahori group of big and small actors, directors and music personalities. Among them was Kardar’s assistant, fellow Bhaati Gate resident M. Sadiq of Chaudhvin ka Chand (1960) fame. M. Sadiq migrated to Pakistan in 1970 but died soon afterwards. I have tried in vain to trace his son, who I heard has a shop on Jail Road, Lahore.

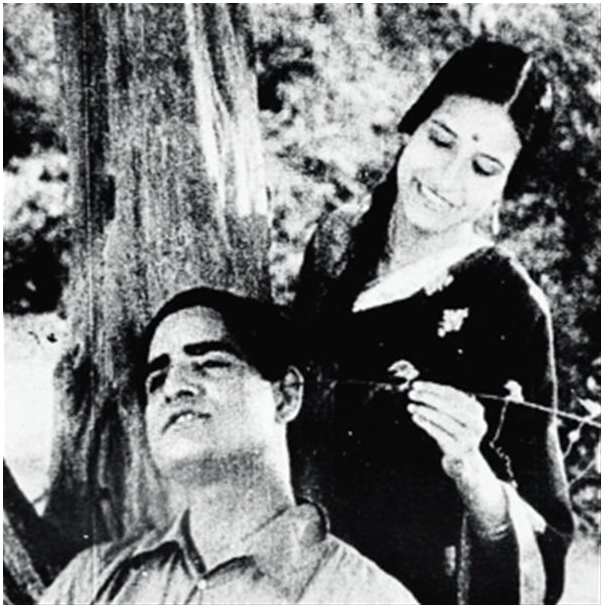

Jamuna Barua with K. L. Saigal in ‘Devdas’ (1936)

The second great Punjabi who first went to Calcutta and then moved to Bombay was writer, lyricist, director and filmmaker Kidar Sharma (1910 – 1999). Sharma was born in a poor Brahmin family of Narowal, district Sialkot, but grew up in Amritsar. His biography by his son Dr. Vikram Sharma, The One and Lonely Kidar Sharma, makes for very interesting reading for anyone wanting to learn about the struggle of an extraordinarily gifted man to find a foothold in the film industry. Initially he faced great difficulties in finding work in Calcutta but then he met Prithviraj Kapoor, who had left Bombay and set up a home in Calcutta. Prithviraj took him to another Punjabi, the one and only maestro Kundan Lal. It was through their auspices that Kidar Sharma finally started working for films. He wrote songs and scripts – and directed them too. His greatest film while based in Calcutta was Devdas (1936) starring K. L. Saigal in the role of Devdas. Later, Dilip and Shahrukh Khan were to play the same role. At Bombay, Kidar Sharma wrote the script and songs for Tansen starring Saigal and Khurshid (Irshad Begum from Chunian, Lahore district). Its music even now fascinates listeners, as Khemchand Prakash used ragas and raginis with great mastery to compose some great songs. Sharma’s absolute masterpiece was undoubtedly Jogan (1950), starring Nargis and Dilip Kumar, with Rajendra Kumar making a short appearance as well. Nargis was to say later that it was one of her best films. In Baware Nain (1950), starring Geeta Bali and Raj Kapoor, the cast and unit was dominated by Punjabis. Music director Roshan composed some of his best songs in that film. In particular, Mukesh’s Teri dunya mein dil lagta nahin became a raging hit. Many years later, Mubarak Begum was to render an outstanding song of his – Kabhi tunhaiyon mein uu tumhari yaad aye gee. It is said that at first Lata Mangeshkar was supposed to sing it, but she found it too difficult and then Mubarak Begum sang it and created magic. Kidar Sharma always maintained high standards – his work was acclaimed by peers as being most artistic and original.

Another Punjabi who rose to stardom soon after the advent of talking-pictures was the singer and actor K. L. Saigal (1904-1947). In a forthcoming article in this series on Punjabi singers who shone in Bombay and Calcutta, we will devote much more space to his inimitable contribution. It was the era of singer-heroes and so he provided some superb acting, but his forte was his singing ability.

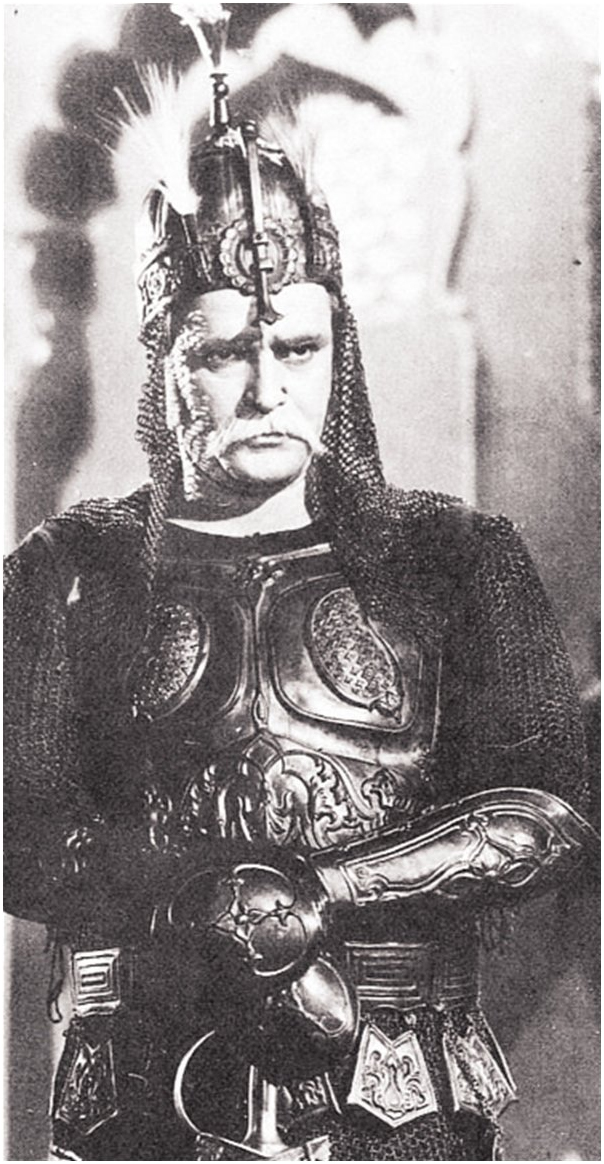

Prithviraj Kapoor, starring in Mughal e Azam

No article on Punjabi pioneers of cinema at Bombay and Calcutta would be complete without highlighting the magnificent contribution of Prithviraj Kapoor (1906-1972). The Kapoors’ family hometown was Peshawar, but Prithviraj spent much of his childhood in Samundri, West Punjab, where his grandfather owned land. Only recently the Pakistani media reported that the current owner of the house had begun to dismantle that haveli because he asserts that it is in such a bad condition that it could collapse any moment. However, the Khyber-Pakhtunkawa government has declared it a national monument and a court order has been moved to stop further demolition work. This should be celebrated by all of us who are acutely aware of Prithivrai’s contribution to stage drama and films. A committed follower of Mahatma Gandhi and a believer in the indivisibility of the Indian subcontinent, his plays Pathan and Dewar were shown for years in Bombay and he would tour India with his huge entourage of actors, technicians, cooks and so on. Yasin Goreja in his book Laxshmi Chowk does point out correctly that Prithviraj’s play Dewar was critical of the Two Nation Theory and Jinnah but the same man was always active in Bombay and elsewhere protesting communal riots and pleading for the Muslims of India not being targeted and victimised. As a nominated member of the Indian upper house of parliament, the Rajya Sabha, Prithviraj pioneered a bill for the abolition of the death penalty.

In any case, when it comes to films, Prithviraj worked both in Bombay and Calcutta and made some memorable films. His career started with the era of silent films and went on into the early 1970s. He played Alexander the Great in Sikander (1941); Judge Ragunath in Awara (1952); and Akbar the Great in Mughul-e-Azam (1960). I personally think his role as as Justice Ragunath in his illustrious son Raj Kapoor’s magnum opus Awara was his greatest acting feat. I saw Awara first in 1962 and then went on to see it 24 times more – on one occasion every matinee show for a week until my pocket money for that month was all spent. That infatuation was disrupted visually when India and Pakistan went to war in 1965 and Indian films could no longer be shown in Pakistani theatres. The idealism of the film, that nobody is born evil or low and we are all largely – if not wholly – a product of circumstances quite beyond our control, was a message that went to my heart readily although I now realise that class barriers can successfully be overcome only in films and never (or rarely) in real life. Prithviraj played the ultra-conservative, stone-hearted judge who abandons his pregnant wife merely on a suspicion to protect his false sense of honour and vanity. The story was written by Khawaja Ahmed Abbas and V. P. Sathe.

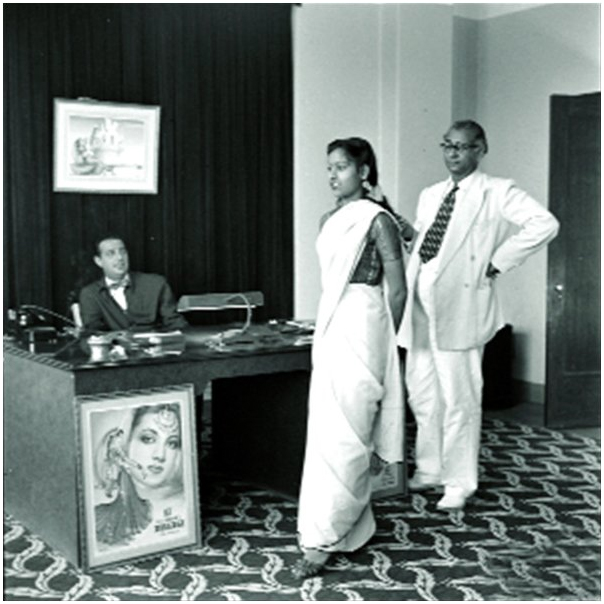

A young woman auditioning for a role in an A. R. Kardar film, circa 1951

Kardar’s presence in Bombay helped to establish a large Lahori group of actors, directors and musicians

Then something happened which brought back Prithviraj into my life. During the summer holidays of 1972, a friend Khalid Mahmood and I decided to pay a surprise visit to another friend, Rana Afzal, who hailed from Gojra – a small town close to Lyallpur (Faisalabad). We arrived in Gojra via Samundri on a hot afternoon and Rana Afzal was indeed the perfect host.

At 1.30 pm, All-India Radio’s Hindi service announced a recorded interview with Prithviraj (he had died a few weeks earlier, but we did not know that). To my great surprise Prithviraj began by talking about his childhood in Samundri and particularly mentioned Hameed Pehalwan with whom he spent much time. He also talked about Peshawar a great deal.

Prithviraj Kapoor criticised the Two-Nation Theory but protested communal riots and stood with Indian Muslims

It was a strange coincidence that Khalid and I had just been in Samundri, perhaps only an hour earlier, where the bus stopped to drop and pick up passengers. To hear someone talk about Samundri from his deathbed thousands of kilometres away in Mumbai was a very moving experience. The irony could not be ignored that we had gone past Samundri, a small hamlet, for the first time in our life, without even having a good look at that rustic community which Prithviraj could not visit after 1947 – although he longed for it until his last moments. It captured the tragedy of Partition. Irrespective of whether it was good or bad politically, it shattered the lives of millions of ordinary human beings. Rana Afzal and Khalid Mahmood belonged to refugee families from East Punjab. Their elders also talked about their lost homes, so the Punjabi trauma had hit all communities devastatingly.

In Stockholm I met Riaz Cheema and we became close friends. The Kapoor saga connected with him too. His maternal uncle Chaudhry Naimatullah and Prithviraj were classfellows first in Edwards College, Peshawar, and later at Law College, Lahore. Both were very keen sportsmen.

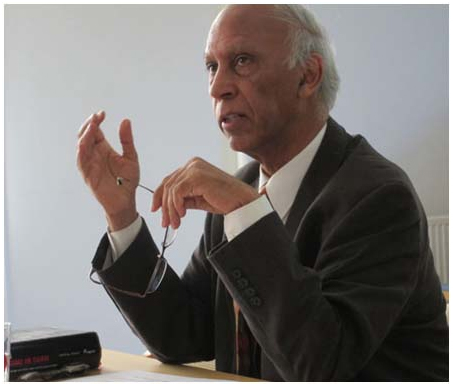

Filmmaker Kidar Sharma, scion of Narowal in Punjab

On one occasion, Naimatullah answered the roll-call in a class at Law College when Prithviraj was playing truant but the teacher immediately sensed that the latter was absent. Both Naimatullah and Prithviraj continued to exchange letters long after Partition.

One day in 1986 I had gone to rent video-films from the Bhatti Brothers in our locality of Sollentuna. There I glanced through the latest issue of Star Dust in which an interview with Raj Kapoor had been published. It began with Raj saying that his family was originally from “Samundru”. I knew Samundri had been mis-spelt as “Samundru”, but it gave me an excuse to write to him. On May 7, 1986 I wrote to Raj in which I mentioned my visit to Gojra in 1972, which had taken me past Samundri and how it coincided with his father reminiscing about his childhood there on All-India Radio. A prompt reply dated May 12, 1986, written on RK Films & Studios official letter-pad, arrived. Raj Kapoor told me that his family hailed originally from Peshawar, but his grandfather retired as Tahsildar from Samundri and settled there. He thanked me for sharing with him my craze for Awara. He then spelled out his vision of the future:

“My conviction is that Humanity ultimately will have to have one religion which shall be based on love, non-violence and deep understanding of ethical values. Sooner or later the geographical and religious barriers will vanish and a new era will begin, the era of love, hope and humanism.”

This idea found expression in RK films’ Henna, which preached India-Pakistan concord. We await its realisation in the world outside films.

Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Stockholm University, Visiting Professor at Government College University and Honorary Senior Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore

Ishtiaq Ahmed is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Stockholm University, Visiting Professor at Government College University and Honorary Senior Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies, National University of Singapore

Curtsey:The Friday Times:29 Jan 2016

|