|

Murder of National languages:

Why only one national language? (Articles)

“The adoption of Urdu as the national language has caused conflict between the different ethnic groups. When Pakistan was created in 1947, the Sindhis, Pashtuns, and Punjabs were surprised that their languages would be given inferior status to Urdu. These groups would have to teach their children Urdu for them to get jobs in the government, military, and business. To compound the problem, the native speakers of Urdu are the Muhajir ethnic group, who emigrated from India to Pakistan and who are not considered native to Pakistan. The native Pakistani population became upset that an immigrant population should be given special privileges over the native population who speak more widely used languages. The privilege given to Urdu has led people to be ashamed of their native language and is threatening cultural and linguistic diversity.

Languages: Conflict Over Language

To Listen click to the link : http://uwf.edu/atcdev/pakistan/web/Languages/4Languages.html

Murder of National languages:

Why only one national language? (Articles)

Why only one national language?

Apparently, ‘images’ of religion and Urdu are produced and reproduced in order to maintain internal unity

Zubair Torwali

As per media reports, the cabinet division has issued a letter to federal departments directing them to use Urdu in their public and official correspondence. The directive also states that the president, prime minister and his cabinet ministers have to make speeches in Urdu in Pakistan and abroad. The media also reported this move as making Urdu the official language of Pakistan and consequently fulfilling the obligation made by the 1973 Constitution wherein it is suggested that English would be replaced by Urdu within 15 years. On May 14 this year, the federal cabinet decided that Urdu would be the official language as per Article 251 of the Constitution.

One must feel jubilant at the new initiative by the PML-N government as Urdu has now, to a great extent, become the lingua franca of Pakistani society despite the fact that it is the first language (mother language) of not more than seven percent Pakistanis. Urdu immersion programmes have been in our educational policies for decades. It is used dominantly in our mass media; the emergence of private television channels during the past decade has popularised Urdu besides the massive production of books, booklets and pamphlets — mostly on religion and poetry — each year. Given the ‘vibrant’ Urdu television channels in Pakistan, Urdu has become an effective means of access to consumers in Pakistan.

This ‘shift’ to Urdu was, however, not a direct outcome of any policy. It was based on commercial and religious pragmatism, as a majority of Pakistanis could not learn English despite being taught in schools from early childhood. What the federal government decided regarding Urdu is plausible. Yet, at the same time, the government’s bias is evident from its behaviour towards the so-called provincial and ‘minority languages’.

There are believed to be 70 living languages in the country, not including English and Urdu. The National Assembly’s standing committee on law and justice rejected a bill seeking national status for regional languages in July last year. The bill, presented by the ruling party lawmaker, Ms Marvi Memon, got only one vote in favour out of five in the said committee. Another bill demanding national status for 14 Pakistani languages is still lying somewhere in the drawers of the National Assembly.

Pakistanis are linguistically compound bilinguals, referring to speakers who have learnt their native language and then another language later in life. With ‘another language’ later in life, Pakistanis are usually immersed in a second language completely. Eventually, they abandon their native language, as it is not taught in schools. This is more common among the elite but the ordinary majority of Pakistanis languishes as it cannot become fully proficient in the native language nor can it learn the second language, whether it is Urdu or English.

On the educational, social and cultural utility of local and indigenous languages, the Pakistani state’s mindset seems ambivalent. This ambivalence about local language education is found among local community members in Pakistan as well, which, in its essence, is the impact of the non-acceptance of linguistic diversity on the part of the state of Pakistan. In Pakistan, parents and communities as well as policy makers are often more confident about the importance of English and to a great extent of Urdu as well, and of the culture associated with these languages than they are of the mother tongue and home culture.

Since religion and the Urdu language have been given a pivotal role in the political ideology of Pakistan, it becomes almost impossible for other expressions of pluralism or multiculturalism to survive within the typical Pakistani mindset. Apparently, ‘images’ of religion and Urdu are produced and reproduced in order to maintain internal unity. The recent official recognition of Urdu is seen by many as a gesture to appease an ethnic political party that was recently in the dock. But contrarily this practice is counterproductive in terms of national cohesion and internal security. On the one end it has directly given rise to extreme political religiosity whereas on the other it has fostered a sense of deprivation and marginalisation within the federating units. In Pakistan, what the power wielders have been doing on every front, whether against extremism, terrorism or separatism, is largely ideological indoctrination so that internal conflicts remain concealed or dormant. No permanent solution to these conflicts is sought.

Very often in Pakistan the argument against the inclusion of the mother tongue in education is given on the pretext that this paradigm has no empirical research behind it. They ignore the fact that in the world’s research, confirming the educational and cultural effectiveness of mother tongue instruction certainly exists. These decision makers are not convinced other than about the pedagogical aspects of mother tongue instruction. It is not the pedagogical factors of mother tongue education that impede its national level adoption. Political and social aspects come powerfully into play when language-in-education issues come under consideration. The working of national language policy is significantly influenced by these political attitudes towards using local language and culture for educational purposes and nation building.

Pakistan is still in search of national cohesion. And for national unity a certain kind of ‘discourse’ is needed. In Pakistan, this discourse changes its shape with the passage of time but never its essence. It exclusively revolves around religion and the existence of an essential enemy.

An elite, which has successfully abandoned its language and culture, wields power in Pakistan. Since this power is naturally not static and changes its centre, ruptures can be seen in the national fabric in the shape of separatism or extremism. In our context, the elite never allows this power to slip away from them, and hence they try to replace ethnic conflicts with religious ones because they think religion is more centripetal. In order to build a nation, the state must accommodate all languages, cultures, religions and sects irrespective of their size and numbers.

Along with making Urdu the official language, the government needs to give national status to regional and minority languages. It must enact measures for the promotion and safeguarding of these languages by including them in education and in the media.

The writer is based in Swat where he heads IBT, an independent civil society organisation on education and development. He can be reached at ztorwali@gmail.com

Curtsey:Daily Times, July 28, 2015

National language, the SC and global reality

English is a pre-requisite to be recognised as a skilled immigrant. The top 100 universities of the world run advanced courses, the medium of which is English

Dr Qaisar Rashid

On September 8, under the lordship of Justice Dost Muhammad Khan, Justice Qazi Faez Isa and Chief Justice (CJ) Jawwad S Khawaja, the Supreme Court (SC) of Pakistan issued orders to the government to implement Article 251 of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan. A critical evaluation is required of both the relevant article of the Constitution of Pakistan and the relevant decision of the SC.

On the issue of national language, Clause One of Article 251 of the Constitution says: “The national language of Pakistan is Urdu and arrangements shall be made for its being used for official and other purposes within 15 years from the commencing day.” In continuation of the same idea, Clause Two of the same article says: “Subject to clause (1), the English language may be used for official purposes until arrangements are made for its replacement by Urdu.” No doubt, Clause One (along with Clause Two) enjoins upon the government to make arrangements to use Urdu for official purposes; neither the Constitution nor the decision of the SC delineates the meaning of the words “other purposes”. It means that the focus of both the Constitution and the SC was on the point of what should be the official language of Pakistan and not more than that. Furthermore, the words “other purposes” do not automatically mean the medium of education.

Clause Three of the same article says: “Without prejudice to the status of the national language, a provincial assembly may by law prescribe measures for the teaching, promotion and use of a provincial language in the addition to the national language.” No doubt, this clause enjoins upon the provincial governments to take measures for teaching a provincial language in addition to the national language, besides promoting and using a provincial language. Neither the Constitution nor the decision of the SC is vocal on the aspect of which language should be declared the provincial language. For instance, in Punjab, Punjabi and Seraike are both spoken. In Sindh, Sindhi and Urdu are both spoken. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pashto and Hindku are both spoken. In Balochistan, Balochi and Pashto are both spoken. Nevertheless, Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto and Balochi are already promoted at the provincial levels. More than that, these languages can be opted for as optional subjects in the examination of the Central Superior Services (CSS) held by the Federal Public Service Commission.

On the issue of right to education, Article 25-A of the Constitution of Pakistan says: “The state shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to 16 years in such manner as may be determined by law.” No doubt, this article makes it obligatory on the government to offer free and compulsory education to all children of a certain age. The article does not finalise the medium of education. Instead, it leaves the space open for “such manner as may be determined by law”. In Pakistan, children already learn their regional mother languages at home for conversational and communication purposes. However, to learn a language for educational purposes is altogether a different matter. Neither the Constitution of Pakistan nor the decision of the SC has addressed this point.

Another point both the Constitution of Pakistan and the decision of the SC have overlooked is that the post-1991 world is governed by mechanics different from those that were operational in 1973. The flow of technology in terms of the internet, computer and satellite has brought the world closer. The resultant global propinquity does not mean dissociation and reclusion but association and communication. Deriding or denigrating English by phrasing it as the “colonial language” is to blink away the fact that English has fast surpassed the phase of a colonial language and is now the current language of understanding, knowledge and global communication.

The origin and outflow of the modern day technological revolution has taken place in English speaking countries. The phenomenon of immigration on the basis of skill continues to enrich host countries with people of talent and abilities. English is a pre-requisite to be recognised as a skilled immigrant. The top 100 universities of the world run advanced courses, the medium of which is English. These universities are overwhelmingly placed in English-speaking countries. Human genetics and gene technology are current medical research areas. No research article is recognised unless it is published in a journal publishing research in English. Despite their historical anti-English rancour, both German and Japanese people have been learning English and their scientists prefer to settle in English-speaking countries. East Europe, which was once a part of the former Soviet Union, has been learning English.

Even the British, the native speaker of English, learn English, especially standard English. In markets, there are available a number of books on the topic of how to write English written for the natives of English-speaking countries. There are incidents where professors in scientific research institutes in the UK were forced to write letters to the government to improve the standards of English (both in terms of grammar and vocabulary) at the school level. The question is this: why is a Pakistani (whether a child or adult) hesitant to learn English? Why is a Pakistani fearful of learning English, a language of science and technology? Is it not a sickness of the mind to dissimulate one’s aversion to English (whether or not rooted in one’s slackness) by hiding behind Urdu or the cliché, the loathsome legacy of the colonial age? The world has entered a phase of pro-active learning but Pakistanis still ask the Constitution and SC to come to their rescue, and both oblige them.

Pro-English realities are so harsh, glaring and adamant that neither the Constitution of Pakistan nor any decision of the SC can save Pakistanis. Neither of them should be incongruent with the age the world and Pakistan are passing through. Let Pakistanis learn English.

The writer is a freelance columnist and can be reached at qaisarrashid@yahoo.com

Curtsey:Daily Times, September 23, 2015

Language debate

BY S H A M I M M A L I K

AFTER almost 70 years of independence, the debate, whether education in Pakistan should be in Urdu or English, rages on. The 1973 Constitution written in English, made Urdu the national language, stipulating that Urdu be the official language as well as the language of curriculum and medium of instruction in education.

While Article 25 in the Constitution stipulated equality for all citizens before the law, Article 25A, enshrined in 2010, addressing the right to education specified that `the state shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to 16 years in such manner as may be determined by the law`. This might be confusing to some but these two articles combined are about `equality` for citizens` right to education.

As this debate continues to be politicised, the present state of education continues to perpetuate class inequality stemming from a failed system of education. As a consequence, by one estimate, 23pc of children in rural areas are deprived of education thus leaving Pakistan with the highest number of out-ofschool children in South Asia and second highest in the world.

Furthermore, since the majority of children from the middle and poor class attend government schools; this puts them on the path of being the future underclass. These Urdu-medium schools are mostly underfunded, provide limited instructional time, and have an outdated curriculum. Moreover, teachers lack the motivation and adequate training or accountability.

As such, the majority of the students get to learn little from these institutions and upon graduation, it becomes a real challenge for them to go for higher education or seek out better job opportunities. This standard of education needs to be upgraded since the whole school system, by and large, is producing a class of people with limited potential to seek out better socio-economic opportunities in order to improve their lives. Since as per Article 25A, `the manner as may be determined by the law` is yet to be legislated, without it, mediocrity continues to be validated as time goes by.

Simultaneously, Pakistani leadership both in the public and private sectors prefer to be fluent in English and send their children to English-medium schools while imposing Urdu on lower socio-economic classes through government-run Urdu me dium schools.

This divide takes place geographically as well. In two of the largest cities Karachi and Lahore, the dividing line is Sharea Faisal in Karachi and Shahrah-i-Quaid-i-Azam (Mall Road) in Lahore with the majority of either class residing on either side. Reality is that English proficiency creates better opportunities for higher education and better job pros-pects. We must understand that a nation`s sense of identity does not stem from a language spoken by a few; it comes from peoples` wellbeing, education, and access to equal opportunities and prosperity. The United States does not have an official language. Though English is the dominant language here, it does not have the status of an official language.

It is important to recognise that almost all the gadgets and inventions are for those who understand English. As the world is getting more flat, technology is creating incredible opportunities and abundance of possibilities to influence the world. It has enormous potential to empower people regardless of their class, religion or geographic location.

In this hyper-connected world, literacy can empower people to democratise, create, innovate and educate. This explosive growth in technology could impact mindsets, opening new horizons.

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan had encouraged Muslims in the 19th century to learn Englishto get better jobs and his advice holds as true today. Indians are far ahead of Pakistanisinlearning English which has opened the doors for them to pursue better jobs and educational opportunities worldwide. In reality,English is going to remain the principal language of internet and technology for many years to come. Therefore, adapting to English proficiency would help the nation become more competitive.

There is overwhelming evidence that early childhood is the most critical period when a child`s brain is most adaptable and as such, early education helps develop a strong foundation. A solid early education produces better life outcomes such as less poverty, better opportunities and a better standard of living.

A well-thought-out and comprehensive strategy needs to be devised to teach English proficiency and computer skills from a very early age. Pakistani leadership must realise that to achieve real excellence, the process would require that the means to receive English language training be available equally to all socio-economic classes. A dualistic approach towards language will continue to perpetuate class differences and inhibit the optimum use of talent in the country. Excellence can only be a self-perpetuating process if access to the means of excellence is to be inclusive and not exclusive. The writer teaches World Literature at the Centre of Global Studies in Norwalk, USA.

shamimmalik@aol.com

Curtsey:DAWN.COM 5/14/2015 |

Medium of instruction: English to Urdu and back

By Aroosa Shaukat

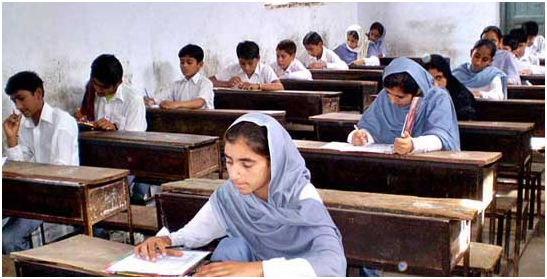

English is medium of instruction for all grades after grade 3, according to govt policy. PHOTO: FILE

LAHORE:

The government’s decision to revert to Urdu as the medium of instruction in public schools up till Grade 3 this year has been met with reservations by some teachers who insist that it should apply up till Grade 5 at least.

In February this year, the provincial government announced that it would revert its decision [taken in March 2009] to implement English as the medium of instruction in public schools from Grade 1. Amidst pressure by teachers, the Punjab government announced that after reviewing the decision and learning outcomes, it has decided to switch the medium of instruction back to Urdu for teaching till Grade 3.

Teachers in the Punjab have welcomed this decision, but with reservations. They have claimed that specifying English as the medium of instruction from Grade 4 onwards would have a “detrimental effect” on children and their learning.

The Punjab Teachers’ Union says the government must revise its decision to make Urdu the medium of instruction only till Grade 3.

PTU Secretary General Rana Liaquat Ali says the government should make Urdu the medium of instruction till Grade 5, and later give students an option to choose between Urdu and English as the medium of instruction. “Children in primary schools are more receptive to learning in their own language,” says Ali.

He says that teachers not only teach in Urdu in classrooms but also in other regional languages. “Whichever language helps a child learn better is most productive for the teacher,” he says. “But a flexible education system and curriculum books that allow children and teachers to work as they feel that is what the government should strive for.”

Razia Aslam, a public primary school teacher of grades 3 and 5, says since most of the students in public schools are from low income households, classrooms should offer a learning environment they can relate to. “The schools should focus on improving the teaching of English as a language or subject – this will help children learn the language and understand concepts of other subjects in their native languages,” she said.

A 2013 report by the Society for the Advancement of Higher Education (SAHE) and the Campaign for Quality Education (CQE) titled Policy and practice: teaching and learning in English in Punjab schools indicates that while 70 per cent of the teachers found it hard to teach Grade 1 mathematics and science in English, a similar percentage of parents approved of English being the medium of instruction from Grade 1. The survey conducted in six districts had concluded that English should be taught as a subject rather than the medium of instruction at least till Grade 5.

The Education Department says there will not be another review of the matter in the near future. Minister for Education Rana Mashhood Ahmad Khan told The Express Tribune that the government will stick to its decision in keeping Urdu as the medium of instruction till Grade 3. He said the department had made the decision in light of several consultations with experts. “We have to understand that there is a right time to introduce English to our children…after that, they might be able to grasp a new language quickly,” he said.

Khan expressed concern over the teachers’ demand to make Urdu the medium of instruction till Grade 5…“Next they’ll demand it be extended even further”. The counter argument here is that English must be introduced as the medium of instruction before the children grow too old, he said there was no end to this debate.

A report by the British Council, the Directorate of Staff Development (DSD) and the Idara-i-Taleem-o-Agahi titled Can English Medium Education Work in Pakistan? Lessons from the Punjab said that of the 2, 000 teachers it surveyed, 56 per cent of the public primary and middle school teachers had “no measurable standard of functional language ability”.

ITA Director Baela Raza Jamil says the government is still “stuck in the colonial times”. “Why can’t Punjabi or other regional languages be made part of the classroom?” she asks. Jamil says that while Urdu can be made the dominant language in classrooms, English and Punjabi can be secondary languages in all primary schools across the province.

“We are a multilingual people and our children are accustomed to it…we need to have an education system that incorporates local languages while gradually transitioning to a foreign language at higher levels.” Jamil stresses that English should be taught as a subject at the primary level, but adds that any decision relating to the medium of instruction should contribute to positive learning outcomes. “If it doesn’t contribute to the learning of children, then regardless of the medium of instruction, it is going to be utterly useless in the end.”

Curtsey:The Express Tribune, March 20th, 2014.

An unfortunate narrative

Sir: It is no one’s fault that the people of the largest province of the country have failed to develop their own language. However, it is total injustice with the people hailing from other federating units, upon whom a language is being imposed without taking them into confidence. The most unfortunate aspect is that this time the narrative about Urdu being an official language has come from the apex court through a verdict without listening to the people of the country. This transpires that no lesson has been learnt from the history. A major part of the country was lost due to the language narrative during early decades after the independence.

How can a language be imposed on a large number of people all of a sudden? Was the honourable court not aware that such a move if forcibly imposed may further divide the people? Although, majority of population love the Urdu language and enjoy its richness in literature and poetry, yet the language is not without controversy especially after the unofficial declaration of one segment of the population as ‘Urdu speaking people.’

It is not prudent to create unwarranted resentment among the people in the name of language. It is hoped that wisdom shall eventually prevail and the honourable court will revisit its verdict.

ABDUL SAMAD CHANNA

Karachi

Curtsey: Daily Times, September 29, 2015

Bias in textbooks

Textbook-writing should be the domain purely of subject specialists and must be free from political meddling.—AFP/File

TO create a more tolerant and inclusive society, it is essential that textbooks contain lessons that foster a spirit of unity rather than fuel divisions.

However, as experts pointed out at a seminar on the curriculum held in Islamabad recently, textbooks of both public and private educational institutions in Pakistan contain material that promotes prejudice.

As one participant of the programme put it, our books did not reflect “love, respect or plurality”, and highlighted divisions instead.

There is, of course, much merit in what the academics highlighted, as Pakistan was a relatively more tolerant place several decades ago than it is today. While the rise of and the free rein given to extremist religious groups in the country has had a role to play in making society less tolerant, the state is largely to blame for promoting a narrow, exclusivist ideology through textbooks.

For instance, it is often pointed out that Pakistan Studies lessons can be problematic in their narrative of the Pakistan Movement; in many cases Hindus are demonised as a community in our textbooks while describing the background of Partition.

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa administration — under the previous Awami National Party government — tried, for example, to interpret the Pakistan Movement in a more progressive and less exclusivist manner. Yet these efforts were reversed when the PTI came to power in 2013, reportedly at the behest of the Jamaat-i-Islami, the party’s coalition partner in the province.

Another issue of concern is that of making non-Muslim students study Islamic material, especially in primary classes.

While Pakistan is a Muslim-majority state, it also has people of other faiths living within its borders, which is why it is unfair to make non-Muslim students memorise Islamic prayers or learn the majority population’s religious rituals.

Perhaps the key to reforming the system and inculcating more tolerant values in our textbooks lies with the provinces, as they have the power to interpret the curriculum.

Textbooks must be purged of all material that promotes hate against any religion, sect or nation and the goal must be to impart lessons that will aid the intellectual growth of students, not make them merely regurgitate ideological slogans.

Moreover, textbook-writing should be the domain purely of subject specialists and must be free from political meddling.

There is much that is wrong with our education system; one essential area that can help set it right is to promote a progressive curriculum that favours peace over bigotry.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, October 5th, 2015

Language change

FAQIR HUSSAIN

The writer has served as secretary, Law & Justice Commission of Pakistan, DG Federal Judicial Academy, and registrar, Supreme Court of Pakistan.

FOLLOWING the Supreme Court’s recent query about measures taken for adopting Urdu as an official language, as mandated by Article 251 of the Constitution, the centre embarked on a flurry of frantic efforts: the information ministry issued directions to all other departments to switch over immediately to the national language. The change should have been effected within 15 years of the promulgation of the Constitution, but nothing could awaken the government from its deep 30 years’ slumber on this requirement until now.

The way in which the measure is being implemented is both unprecedented and unwarranted. Summaries and minutes of meetings and communications between the ministries are to be made, and tests for induction in government service are to be conducted in Urdu. No homework has been done and no training given to public officials. The result will be a disaster; the further lowering of standards and deterioration of service quality. This is not in line with the dictates of the Constitution.

Article 251(1) stipulates that “arrangements shall be made” for using Urdu as an official language, which means a lot of homework including translation of laws, rules, regulations and training, etc., before embarking on the venture. Further, the said article provides for “the teaching, promotion and use of provincial language”, which requirement does not find mention in the government directions.

Language, anywhere in the world — more so in Pakistan — is a sensitive, indeed, divisive issue, and must be handled with due care. We cannot shut our eyes to our bad experience when the people of former East Pakistan revolted against the suggestion of no less a personality than the Quaid for adopting Urdu as an official language. The response was harsh, resulting in a popular movement, led and sustained by intellectuals, especially the academic faculty and students of Dhaka University, who argued for Bengali as their national and official language.

Let us not ditch English with the stroke of a pen.

The argument was acceded to only after prolonged civil unrest, riots and bloodshed on Feb 21, 1952 (a day later designated by Unesco as International Mother Language Day). It was the beginning of the process of dismemberment of united Pakistan. The language riots in 1971-72 in Sindh are also still fresh in the memories of people, especially its destructive effects on ethnic and racial harmony in Karachi and Hyderabad.

We must not lose sight of the practical realities: Pakistan is a multiracial/multilingual nation, with six major and some 50 minor languages spoken by diverse ethnic communities and nationalities. The number of Urdu speaking people is reportedly barely 7pc, compared to 44pc Punjabi, 15pc Pakhtuns, 14pc Sindhi, 10pc Seraiki and 5pc Baloch.

Sindhi and Pashto are relatively developed languages, used as medium of education at the elementary level and medium of instruction for higher learning in certain disciplines. They are strong candidates for being adopted as provincial languages. Urdu, though spoken by a minuscule segment, is, however, making gains and increasingly being used as the lingua franca in the urban belts of the country; with the rural areas as alien to it, as they are to Greek.

To do business in Urdu, the non-Urdu speaking population will have to make as much effort as they need to do in learning any foreign language. It is therefore unfair to ask them to switch over to Urdu for use as an official language and/or taking tests for appointments to government posts. They will clearly be at a disadvantage, as they are not being given an even playing field.

This is unfair, and violates Articles 25 and 27, which prohibit discrimination and provide for equality of rights, of opportunities and before law. This will also be a violation of Article 28, providing for the “preservation of language, script and culture”. It is impermissible to establish a system of governance, based on discrimination and racial or lingu-

istic hegemony or domination.

Let Urdu continue its slow and gradual march of gaining popularity and attaining its rightful place as the lingua franca in the country, both in urban and rural regions. Let the government facilitate the process through translation of laws and other material in Urdu and the training of public officials and others.

Let us not ditch English with the stroke of a pen. It is the language of advanced civilisation and the medium of instruction for higher research and studies. With globalisation, the modern age of computer and IT, it offers the key to the future. Countries in a much advanced stage of economic development and technological advancement, like China, are introducing English in their teaching institutions, because it is beneficial for accelerated growth and development.

It will be a tragedy, if we in Pakistan squander this important resource due to the myopic vision and rash decisions of our leaders.

The writer has served as secretary, Law & Justice Commission of Pakistan, DG Federal Judicial Academy, and registrar, Supreme Court of Pakistan.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM ,July 14th, 2015

ZUBEIDA MUSTAFA

The writer is the author of The Tyranny of Language in Education: The Problem and its Solution.

LANGUAGE continues to be an enigma in Pakistan. For the umpteenth time education is being ‘reformed’ in this country. Federal Minister of Planning and Development Ahsan Iqbal has now announced that ‘Urdish’ will be used as the medium of education in the country.

This is the first time Urdish (not Urlish) is being introduced officially. According to the minister, this initiative will rid the country of the “English medium-Urdu medium controversy that has damaged education standards and adversely affected the growth of young minds.”

Explaining the connotations of Urdish as a medium, the minister said that English terminologies of science and technology would be blended with the Urdu narratives rather than adopting Urdu translations. No one has really quarrelled with that; many English words have become so integrated into Urdu that they are generally familiar and it would create problems to introduce newly coined convoluted Urdu terms. I always use the word television when I speak of the idiot box in Urdu as I don’t know of an Urdu equivalent. But I do protest when the Urdu word ‘awam’ is substituted by the word ‘commoners’.

When children are denied their own language, they never learn to think.

However, if the minister believes such gimmickry will satisfy those who clamour for English, he is wrong. Moreover, the introduction of Urdish will not boost students’ academic achievements or teach them civic responsibility and respect for diversity and tolerance, as the minister seems to believe.

That said, the three other initiatives Mr Iqbal promised simultaneously could change the education scene if implemented honestly and in earnest. They are: altering the curricula, reforming the examination system while making it transparent, and training the teachers. These as well as the language issue lie at the crux of the education crisis in Pakistan today.

It is shocking that even very intelligent and highly educated educationists fail to understand the direct relevance of language to academic standards.

Primary education is the base of all education. If it is flawed it will be difficult for it to sustain the weightier structure of higher education. Since ours is not a child-centric society we tend to ignore the needs of children when they start school. We also tend to confuse the use of a language as a medium of instruction and the teaching of one as a second language.

Our ignorance and politicisation of language issues has led to mass confusion and also resulted in the unnecessary controversy that the minister referred to. Young children instructed in their mother tongue have a better understanding of what they are taught which facilitates their cognitive development. Moreover language is the vehicle for thought and when children are denied their own language, they never learn to think.

It is time we re-thought our aspiration to use English as the medium in school, something that the minister has tried to gloss over with his idea of Urdish. We need to shed the myth that by using English as the medium we can kill two birds with one stone: teach children English as well as the subject being taught. In reality they learn neither.

If these arguments make no sense, the basic facts should be more convincing. There is empirical evidence that a preponderant majority of teachers in Pakistan are not proficient in English. When the Punjab government tried to introduce English as the medium of instruction in 2013, it had to rescind its orders a few months later. The teachers actually pleaded with the authorities to spare them this torture as English was not their forte.

As it is, teachers also need to be trained in pedagogy and the subjects they are teaching. Burdening them with English as well is a recipe for disaster. Why not make a beginning in our own languages?

That doesn’t mean that children don’t need to learn the basics of English as a second language. That can be taken care of by training only the required number of teachers as English language teachers who should know the modern methods of language teaching.

Language also has a social dimension that impinges on the employment sector. We are made to believe that English is good, Urdu/indigenous languages are bad. This is not true. The quality of education depends on the quality of teaching, textbooks and, above all, how much a child is motivated. The argument that we do not have books in our own languages smacks of ignorance. Textbooks are developed in response to demands. If this approach is adopted, by the time children complete their schooling, the small percentage of children who opt for higher/technical education could build on their basic knowledge of English to become bilingual. The others would still find productive jobs that do not require expertise in English. We must shed our bias against our own languages.

The writer is the author of The Tyranny of Language in Education: The Problem and its Solution.

www.zubeidamustafa.com

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, August 21st, 2015

Arabicising Pakistan

RAFIA ZAKARIA

In an official function held in the ancient city of Taxila, this past Saturday, the Federal Minister for Religious Affairs Sardar Mohammad Yousuf had some important news for the country.

Speaking to the press at Wah Cantonment, the Minister announced that groundwork was complete for the introduction of Arabic as a language in the secondary school curriculum.

The project would begin in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the Minister added, before going to discuss the arrangements that the Government has been making to facilitate the upcoming Hajj pilgrimage.

The project of Arabicising Pakistan, the painstaking wiping away, hammering out breaking off and denunciation of all parts of our past that do not fit into an imagined always Muslim-ness is not a new one.

The reconstruction of old leaders to fit into new guidelines of piety and purity, the banning of customs, the destruction of structures, the dereliction of art are all part of a long list of things to do to accomplish the project of becoming more 'authentically religious'.

Adding Arabic as the fourth language, on top of English, Urdu and a regional language thus fits into the process of purification currently underway.

It would, however, be wrong to pin this latest development simply to the yearning for Arabness that preoccupies so many Pakistanis. Its practical usage, unrelated to religion, is the fact that Pakistan is one of the most prominent suppliers of manual labour to the Arab speaking GCC countries.

According to the International Organisation of Labour, Pakistan is the second among South Asian nations sending migrant workers abroad. Nearly 7 million Pakistanis have left the country in recent years for the purpose of finding a job and 96 per cent of them make their way to the GCC countries, closely followed by Saudi Arabia.

Once in Saudi Arabia or Dubai or Abu Dhabi, theirs is a grim reality. The kifalah system of sponsorship that gets them there insures that they are already deeply in debt before they ever start working.

As has been reported in a recent front page story in the New York Times, the workers usually do menial jobs in construction, garbage disposal, cleaning, ground crews and such. They live in labour camps in deplorable conditions, sometimes 10 or 15 in a single room, with any clothes they may wear and any food they may eat crammed in between the bunks.

Often, employers refuse to pay them, or pay them months after they are due. The recruiters to whom they owe money take anything they get, before any money can be sent home. If they complain too much, there is always the prospect of arrest. They receive no legal advice, no lawyers and no leniency. Punishments are the only certainty.

Given these conditions, a few ideas emerge regarding what sort of Arabic must be taught to Pakistani students, who if they are lucky, can join the ranks of others in Gulf countries where glorious things called jobs still exist.

Given the large numbers doing ground keeping work or trash collection, perhaps a rudimentary vocabulary in communicating things like, “May I empty this trash can” or “ I have polished this floor” could add to their skills.

Even more crucially, the Arabic that is planned must include at least a few lessons on how to reclaim owed wages and scold unscrupulous employers. A Pakistani construction worker, that can, in Arabic ask why three months of wages have not been paid, and why his passport is being withheld, is far more powerful, than a Pakistani that is mute, silent and accepting of all the abuses that are mercilessly heaped on him by his Arabic speaking masters.

Finally, some Arabic stipulations for emergency situations, such as the one I recounted in this blog a few months ago, when a young man from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was found dead in Makkah; in situations such as that one, it would have been useful if the Pakistanis working with him had been able to ask, “who killed my friend” and “where can I find his body”.

In the particular case, Saudi officials insisted that the young man had simply committed suicide. That it is said, is the usual excuse given to the deaths of poor Pakistani labourers, so that restitution payments are not owed to their families.

In the proposed new Arabic curriculum, it would be useful to teach the parents of such would be labourers to say, “My son did not commit suicide” or to be able to articulate in Arabic the following simple request:

“I want justice for my son, who was Pakistani”.

Rafia Zakaria is an attorney and human rights activist. She is a columnist for DAWN Pakistan and a regular contributor for Al Jazeera America, Dissent, Guernica and many other publications.

She is the author of The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan (Beacon Press 2015). She tweets @rafiazakaria

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, PUBLISHED MAY 23, 2014

Language of instruction

ASIFA SAEED MEMON

THERE has been some debate in these pages recently about the ideal language of educational instruction.

One side argues that English is the lingua franca of the world. Never before has a language been as widely used as the common language of business, government and science. Increasingly, it is the language of higher and technical learning.

This alone highlights the necessity of education in English as we strive to compete and stay relevant in a globalised economy.

On the other side, critics weave together anti-colonialism and dissonance between dominant-elite and oppressed-working class narratives into a case against the use of English as the language of instruction.

This side also highlights the pedagogical difficulties of teaching English to children who speak a different language at home.

It may also be mentioned as a point for the ‘against English’ argument that there simply are not enough trained teachers who can provide instruction in English or teach the language itself if we were to switch to instruction only in English.

It is a good thing that this is being debated, notwithstanding the irony of this happening in the language of our supposed colonial overlords. In important ways, it appears to me, both the ‘for English’ and ‘against English’ camps are missing the real issue.

Pakistan is not the only country where people have raged against the use of English at the expense of the native tongue.

Japan, France, China and many others have tried to stem the tide and have failed. Governments in many Asian countries are now funding English-language training and immersion programmes out of fear that their scientists, engineers, doctors and economists might fall behind the rest of the world. In many non-English speaking countries, universities and technical colleges are switching to English as the language of instruction.

Policymakers in a number of low- and middle-income countries have come to the conclusion that fluency in English as a second language is a ticket to technological and economic development for their citizens, individually, and the economy as a whole. This is not some dastardly conspiracy; it is just a fact. As Greek was the language of upward economic and social mobility under the Hellenic empire, Latin in Rome, Arabic under the Caliphates and Persian under the Mughals; so English is the enduring legacy of the British Empire. This may be a colonial leftover, but nobody is forcing it on us.

Perhaps what has been lost in this debate is parental choice, and what forces inform and motivate that choice. Parents make educational choices every year. One of these choices is about the language in which they would like their children educated and this is informed by two broad factors.

First, is an ethno-linguistic; there is a tussle between Urdu and the multiple languages that are spoken in Pakistani households. Many children grow up with a language at home that is neither English, nor Urdu. In such households there are complex identity politics at play. This, of course varies from province to province and ethnicity to ethnicity.

It would be a mistake to enforce in such a context a state-imposed requirement that teaching be in the national language instead of the ‘colonial’ language. The imposition of one language has been tried in the past with unhappy results. The idea that we need to come together and decide one language in which all and sundry ought to be educated has a certain neat appeal to it, but it ignores the ethno-linguistic realities of Pakistan.

Besides, while we debate the matter, it appears that parents and schools have resolved this problem in a mutually agreeable way. In many urban areas public schools often offer parallel classes for students where the medium of instruction is Urdu or the local language.

These schools often operate near low-fee private schools that offer education in English. This neatly sidesteps the problem and allows parents to choose. Whether instruction in one language leads to better educational outcomes than another is an important question and research needs to be conducted in that direction. Even if such research finds in favour of Urdu (or a regional language), it does not follow that and enforced choice on behalf of the parents and their children is possible (legally or ethically).

This brings me to the second and, arguably, more important factor: economics. These choices are informed by their assessment of potential future economic and social prospects for their child. It can be debated whether they have all the information necessary to make the ‘right’ choice, but surely the choice has to be theirs.

Finally, there is the problem of matching the demands of the labour market and what we teach at school. To be sure, education is not only about enhancing employability and earning potential but those are major motivating factors behind enrolment decisions. And the language that ensures greater success in important fields of study and employment is English.

Frankly, as it stands today, Urdu (or regional languages) just does not have the vocabulary or grammar to provide an efficient medium for the imparting of knowledge about physics, medicine, mathematics or computer engineering. This largely applies to the middle and high income households, however, and they are already receiving all their education in English.

When it comes to working-class professions fluency in English is largely immaterial. This one fact ensures class rigidity as poor parents have to weigh limited potential economic opportunities in a non-meritocratic society against the potential extra costs of education in a non-native language. How we resolve that is the real question.

The writer is an Islamabad-based policy analyst.

asifsaeedmemon@gmail.com

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, — PUBLISHED JUN 09, 2012

Mother tongue first

UMAR FAROOQ

The report recommends that support should be given for advocacy of adoption of multiple languages in education. – APP (File Photo)

A fascinating report released recently by the British Council Pakistan on the role of language in education in Pakistan, suggests that Pakistani students are best served by education if they are to be instructed in their mother tongues.

The report also suggests that Islamic madrassas are extremely interested in learning English so they can promote Islam in other countries, learn about other religions, communicate their message to the world in a better way, improve image of Islam in the world as well as the basic need for Muslims to learn knowledge.

Titled Teaching & Learning in Pakistan: The Role of Language in Education, the report (prepared by Hywel Coleman and the British Council), was based on the results of a widespread research and survey of the many languages spoken in Pakistan and the country’s education sector.

Some of the findings in this context are: - Language breakdown of Pakistanis by mother-tongue are: (Punjabi) 49.3 %, Pushto 12.0 %, Sindhi 11.7%, Urdu 6.8%, Balochi 3.6%, Brahui 1.3 % and Farsi 0.6 %. - Urdu tends to remain the medium of instruction except for a few English schools. - Class 3 students are not able to write simple sentences in Urdu and do not recognize simple words in English. They are in effect functionally illiterate and innumerate. - English is involved in two contexts: as a subject, as the medium of instruction - While intention is good for use of English as medium of instruction, its impact is negative.

The report insists that education in mother tongue is more effective especially in early years because:

- There are no barriers to comprehension as formulation of basic concepts takes place in mother tongue. - Children learn to read and read more quickly and easily in a language they are already familiar. Making connections between sounds of a language and signs on a written page is more effective when those sounds are repeated more often. - The same language spoken at home, so learning can be reinforced. This also enables the parents to get involved and monitor and contribute to children’s education. - Children can relate their learning in school with their home environment, the games they play, the TV programs they watch, their interaction with other students if all of this is in the same language. - All communities feel equally respected if their home languages are employed. Using a language in school that people do not understand leads to political and social instability and conflict. Particularly important for Pakistan as it is one of 11 countries with high levels of “fragility of conflict” and one of 19 countries with high linguistic fractionalisation - Survey of 22 countries suggests that choice of first language affects educational attendance, performance and explains half of the reason for low retention rates. This is particularly relevant for women. - All things being equal, children are likely to achieve greater proficiency in English if they first study in their home language and then study English as a foreign or second language. - Only 5 % of Pakistanis have access to education in their first language.

The report thus recommends that support should be given for advocacy of adoption of multiple languages in education. But it also notes that education in multiple languages is logistically difficult to arrange for in Pakistan. However since the seven major languages in Pakistan are first language for 85 pe rcent of the school population, these can be used as medium of instruction right at the start.

The report points out that international experience suggests that adoption of multiple languages for primary education strengthens loyalty of ethnic minority towards the state.

Based on these findings, the report then goes on to make some potent recommendations for education in Pakistan till the year 2020.

The following is how the recommendations have been devised:

- Nursery Education : Learn to speak mother tongue language - First 3 years: Introduction to alphabets, learn to read and write in their mother tongue. (Scripts for local language and Urdu are either same or very similar.) - Class 3-5 : Urdu is introduced and gradually replaces regional language as the language of instruction. By 5 this transition is complete. Regional language is a subject not medium of instruction but still taught as a subject. - Class 6: Children should be confident and fluent in Urdu by now. Roman alphabet and English are introduced. English is studied as a main subject for four years (grade 6-9) - Class 10: English becomes medium of instruction; Urdu and regional languages become subjects. - Entrance exams for civil service, other employment and universities will require that candidates are good in all 3 languages (Urdu, English, regional language). This will help them serve their people better and oblige elite schools to teach local language.

The British Council report will be officially launched on Thursday.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, PUBLISHED OCT 21, 2010

War on language

NAZIHA SYED ALI

WHILE visiting Balochistan, one becomes aware of just how removed that province is from mainstream Pakistan. And it’s not only the obvious things — such as the dire lack of development, the air of oppression or the stories of enforced disappearances and dumped bodies. There’s also the more subtle issue of language.

According to Article 28 in the chapter on fundamental rights, the Constitution says: “… any section of citizens having a distinct language, script or culture shall have the right to preserve and promote the same and subject to law, establish institutions for that purpose”. Most of the national conversation on this is centred on the fact that many private schools, at least in urban areas, do not teach the relevant provincial language in contravention of provincial laws to the effect.

In Turbat some weeks ago, I learnt that the situation is quite the opposite in Balochistan. This is the only province where government schools do not teach either Balochi or Brahui, the two most widely spoken native languages outside the Pakhtun-majority areas in the north of the province. Balochi is only taught in a few private schools here.

Public schools in Balochistan teach neither Balochi nor Brahui.

One of the most devastating weapons of repression employed by a state is the suppression of a native language.

History is replete with examples of forcible assimilation of a people in this manner. To exclude the teaching of a native language while imposing on its speakers the language of the dominant polity is exactly what it sounds like — an act of cultural warfare. Language is an inherent part of a people’s identity, the repository of their history and culture, a record of epic battles fought and of heroic exploits for its generations to emulate.

It could be argued that education is a provincial subject and that, if it so chose, the National Party-led government could take measures to address the issue, but in Balochistan’s case it is the establishment that has the final say in keeping with its ‘security imperatives’.

Is it any surprise then that at Turbat University, the most popular department by far is that of Balochi, an elective subject at this stage? Even though the faculty and students maintained that political discussions take place in the classroom, there can be no greater political statement than that. By the time they reach college-going age, many young Baloch are keenly aware of the establishment’s ‘special’ handling of their province.

Balochi itself is said to be remarkably rich especially in its poetic tradition. A senior faculty member at the university told me he had compiled a book of 1,000 Balochi proverbs originating in the western part of the province alone.

At the Balochistan Academy, also in Turbat, with its ill-stocked, rickety looking bookshelves, I was invited to take a look at a room full of dusty cartons filled with Balochi books, both poetry and prose. These had been returned by the eight bookshops in town spooked by raids carried out by the Frontier Corps over the last year to confiscate ‘subversive’ and ‘extremist literature’. (Similar raids were also carried out on bookshops in Gwadar city.) Most of the ‘objectionable’ material, however, was literary works of fiction in the native tongue.

Bookstores in the province’s Makran belt — where both Gwadar and Turbat are situated — don’t carry Balochi books since mid-2014. Works by Gandhi cannot be found here either. Ostensibly Gandhi elsewhere in Pakistan is kosher. And so apparently is printing Balochi books; the publishers in Karachi have not been harassed, picked up or beaten.

For the Academy, which places orders with Karachi-based publishers for Balochi books that it then sells to these bookshops, it means the suspension of an important source of income. The institute receives an annual grant of only Rs500,000 from the provincial government, far short of even basic requirements.

Most of the books for the Balochi curriculum taught in the private schools and language centres in Balochistan come from Karachi, printed under the aegis of the Zahoor Shah Hashmi reference library in the city. However, several language centres have closed down, particularly in areas where the army presence is high, such as Mashkay, and demand has been steadily declining. No orders have been placed for new books since two years.

The words of one of the library’s administrative staff are telling. Speaking about the teaching of Balochi in Balochistan he said: “We don’t have funds to ensure that classes are always held in a purpose built place. Sometimes someone volunteers their home, or we even sit under a tree. We nominate people who are responsible and whom we can trust to hold such classes and we send them the books.”

When the teaching of their native language is considered a subversive act, how can we expect an ordinary Baloch to feel anything other than alienation at the hands of the state?

The writer is a member of staff.

naziha.ali@dawn.com

Published in Dawn, April 8th, 2015

Punjab and Punjabi

THE United Nations has fixed Feb 21 as International Mother Language Day. … Unfortunately Punjabis usually keep away from their own language. They not only lower the prestige of their language but expect the same attitude from speakers of other languages towards their mother tongues. People who love their language are not liked…. That is why they did not favour the demand for Bengali…. Violence and bullets were the result. The clash ultimately divided the country into two. If Punjabis had been in love with their own language, they would not have opposed the Bengalis’ demand. And perhaps the tragedy of Dhaka would not have taken place.

Punjabis never favourably evaluated the demand of the Sindhis and Pushto-speaking people. Consequently, Punabi has [acquired a negative image] in the country. This … will continue till Punjabis start loving their own language. Only those who love their mother tongue, respect the language of others. The label of ‘national’ should not mean the promotion of one language at the cost of another. This is unfair.

…[T]he first step needed is to introduce Punjabi as a medium of instruction at the primary level. All artificial projects to ‘promote education’ should be stopped forthwith and billions of rupees be directed towards the promotion of education at the people’s level…. For that, the only step is to make Punjabi the medium of instruction at the primary level. …Apart from changes in the education system … Punjabi should be made the official language of the province. The Punjab government should extend a helping hand to [boost] Punjabi publications. The past Punjab government had established cultural and linguistic institutions.

More such institutions … should initiate serious work. A Punjabi language authority should also be established. Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif … is soft towards victims of oppression, injustice…. The Punjabi language … needs the same care [and] sympathy….

Selected and translated by STM.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM, — PUBLISHED FEB 24, 2012

Education in Punjabi

PUNJAB education minister Rana Mashood has conveyed to the provincial assembly the decision to recruit 28,000 educators during the current year to overcome the shortage of school teachers. An enrolment emergency will be imposed from Aug 14 to admit four- to 14-year-old children to school. Speaking … on Friday he said the provincial government was amending the Scheme of Studies for 2007, and steps would be taken to promote the mother tongue. He said the government wanted every child in the province to get an education…. The government had allowed the teaching of Punjabi from class 1 to 5. …No right thinking person can oppose what the minister has said. At least to the extent of making claims, the Punjab government has been boasting of doing a lot to promote education…. This process began during Pervaiz Elahi’s government….

The previous PML-N also made tall claims about promoting education. The basic things the champions of education have always ignored include providing an education in the mother tongue and ensuring 100pc enrolment of children at the primary level. People in our country are no longer interested in educating their children because of inflation, unemployment and other problems. Rather than sending their offspring to school, the working class believes it is better to make them learn skills so that they are able to earn. It is useless to think of attaining 100pc literacy rate with such thinking.

The second issue is making the mother tongue the medium of instruction. …Our leaders are opposed to Punjabi, even allergic to it. They become annoyed whenever Punjabi is mentioned. …Our bureaucracy will create hurdles in the way of making Punjabi the medium of instruction…. The goal can be achieved only if the chief minister himself takes an interest. — (July 29)

Selected and translated by Intikhab Hanif.

Curtsey: DAWN.COM, AUG 03, 2013

Regional languages

I am a Pakhtun in love with the Punjabi language. I really enjoy the songs of Abrarul Haq, Daler Mehdi and other Punjabi singers. Whenever I hear Bushra Ansari speaking Punjabi in a television drama, I wish she never stops. But, regrettably, most Punjabis who I know speak Urdu and very few among their younger generation speak or understand their mother tongue. While Urdu is the lingua franca in our country, and the national language, it is unfortunate that we are neglecting our regional languages.

The situation is even worse in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Just as the educated or well-to-do prefer to say ‘duss’ instead of ‘luss’, and do not use Pushto numbers, the TV channels in Pushto are also turning into semi-Urdu channels gradually. The anchors, singers and actors do not appear to be promoting the Pushto language and often switch over to Urdu or English in some cases. In English-medium institutions, Urdu is used by Pushto-speaking teachers to talk to Pushto-speaking students. Isn’t it a matter of shame that we are neglecting our regional languages?

Jahanzeb Khan

Peshawar

THE NEWS,Monday, December 10, 2012

The clash of languages

Sajid Hussain

Karachi

Overawed faces were fixed at Vikram Seth. The snake-shaped line of anxious people waiting to get their freshly-bought books signed by the British novelist of Indian origin was growing in length. Pakistan’s celebrity English novelist Mohammed Hanif, sitting next to him, was equally engrossed in signing copies of his ‘Our Lady of Alice Bhatti’; though he had enough time to occasionally run his fingers through his unkempt hair. A couple of yards from the writers’ signing booth was sitting Urdu’s greatest living fiction writer, Intizar Hussain, alone, with enough time to devote himself to reading a book.

“English is also a regional language,” joked Hanif, while moderating a session on Pakistan’s local languages a little earlier, after one of the speakers apologised for speaking in English.

“Yes, it’s the language of [Defence] Phase VIII,” quipped one of the participants.

The clash of languages was conspicuous throughout the session, and throughout the festival. English writers had a clear dominance, which was felt by many. But linguistic prejudices were not restricted to English and Urdu. When Sindhi poet Amar Sindhu read one of her poems’ Urdu translation, many in the audience questioned why was she embarrassed to recite her poetry in Sindhi. “I see linguistic riots erupting,” Hanif, who himself composes poetry in Punjabi, played another wisecrack. “The venue [of the festival] is quiet safe from riots,” replied Pashto poet Ahmad Fawwad, implying that the area was posh enough to be safe.

There was a general perception that if the event was held at the Arts Council Karachi, which is located in the middle of the city, writers of Urdu and local languages would have felt less lonely.

However, despite light-hearted and tongue-in-cheek references to class and linguistic biases, the session on local languages seemed more lively, interactive and friendly than any other session. “At least I could say something,” an acquaintance told me after the session. “The other sessions ended before I prepared a grammatically correct question in English.”

THE NEWS, Monday, February 13, 2012

Saving local languages

Zubair Torwali

The cabinet division recently issued a letter to other federal departments directing them to use Urdu in their public and official correspondence. The directive also states that the president, prime minister and his cabinet ministers have to make speeches in Urdu when in Pakistan or abroad. The media also reported on this move as one that makes Urdu the official language of Pakistan, fulfilling the obligation made by the 1973 constitution wherein it is suggested that English would be replaced with Urdu within fifteen years. On May 14 this year the federal cabinet decided that Urdu would be the official language as per Article 251 of the constitution.

One must feel jubilant at the new initiative by the PML-N government as Urdu has now, to a great extent, become the lingua franca of Pakistani society, despite the fact that it is the first language (mother language) of not more than only seven percent Pakistanis.

Urdu immersion programmes have been in our educational policies since decades. It is used dominantly in our mass media; and the emergence of private television channels during the past decade has popularised Urdu. Besides that, there are a number of books, booklets and pamphlets – mostly on religion and poetry – produced each year in the Urdu language. Given the ‘vibrant’ Urdu TV channels in Pakistan both Urdu and religion have become the most effective means of access to consumers in Pakistan.

This ‘shift to Urdu’ was not a direct outcome of any policy. It was based on commercial and religious pragmatism, as the majority of Pakistanis couldn’t learn English despite it being taught in school from early childhood.

What the federal government decided regarding Urdu is plausible. Yet at the same time the government bias is well evident from its behaviour towards the so-called provincial and ‘minority languages’.

There are believed to be 70 living languages in the country, not including English and Urdu. The numbers of speakers of these language range from 150 (Aer language) to 61 million (Punjabi).

The National Assembly Standing Committee on Law and Justice rejected a bill seeking national status for regional languages in July last year. The bill presented by the ruling party lawmaker, Marvi Memon, got only one vote in favour out of five in the said committee. Another bill demanding a national status for 14 Pakistani languages is still lying somewhere in the drawers of the National Assembly.

Pakistanis are linguistically ‘compound bilinguals’ – referring to speakers who have learnt their native language and then another language later in life. With the ‘another language’ later in life Pakistanis are usually immersed in a second language completely. Eventually they abandon their native language, as it is not taught in schools. This is more common among the elite. The ordinary majority suffers most as it cannot become fully proficient in the native language nor can it learn the second language – whether Urdu or English.

On the educational, social and cultural utility of the ‘local’ and ‘indigenous’ languages the Pakistani state mindset seems ambivalent. This ambivalence about local language education is found among local community members in Pakistan as well which, in its essence, is the impact of the non-acceptance of the linguistic diversity on the part of the state of Pakistan. In Pakistan the parents and communities as well as policy makers are often more confident of the importance of the English, and too a great extent of Urdu as well; and of the culture associated with these languages than they are of the mother tongue and home culture.

Since religion and the Urdu language have played a pivotal role in the political ideology of Pakistan, it becomes almost impossible for other expressions of pluralism or multiculturalism to survive within the typical Pakistani mindset. Apparently the ‘image’ of religion and Urdu is produced and reproduced in order to maintain internal unity.

But contrarily this practice is counterproductive in terms of national cohesion and internal security. On the one end it has directly given rise to an extreme political religiosity whereas on the other it has fostered sense of derivation and marginalisation within the federating units. In Pakistan what the power wielders have been doing on every front, whether against extremism and terrorists or separatism, is largely ideological indoctrination so that the internal conflicts remain concealed or dormant. No permanent solution to these conflicts is sought.

Very often in Pakistan the argument against the inclusion of the mother tongue in education is given on the pretext that this paradigm has no empirical research behind it. They ignore the fact that research confirming the educational and cultural effectiveness of mother tongue-medium instruction certainly exists. These decision-makers are not convinced on any ground other than the pedagogical aspects of mother-tongue instruction. It is not the pedagogical factors of mother tongue education that impede its national level adoption. Political and social aspects come powerfully into play when language-in-education issues come under consideration. The working of a national language policy is significantly influenced by these political attitudes towards using local language and culture for educational purposes and nation-building.

Pakistan is still in search of national cohesion. And for national unity a certain kind of ‘discourse’ is needed. In Pakistan this discourse changes its shapes with the passage of time – but never the essence. It exclusively revolves around religion and the existence of an essential enemy.

An elite that has successfully abandoned its language and culture wields power in Pakistan. Since this power is naturally not static and changes its centres hence ruptures can be seen in the national fabric in the shape of separatism or extremism. In our context the elite never allow this power to slip away from them; so they try to replace ethnic conflicts with religious ones because they think religion is more centripetal than the others.

In order to build a nation the state must accommodate all languages, cultures, religions and sects – irrespective of their size and numbers.

Along with making Urdu the ‘official language’ the government needs to give a national status to the regional and ‘minority languages’; and enact measures for promoting and safeguarding these languages by including them in education and in media.

The writer heads IBT, an independent organisation dealing with education and

development in Swat. Email: ztorwali@gmail.com

THE NEWS, Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Zubair Torwali

What happens when a language dies might be an irrelevant question for those who think English is a symbol of civilisation, the means of development and the bearer of progress. But language scientists think otherwise. They assert that any language – written or spoken – is the bearer of an individual’s, a community’s or a nation’s culture, identity and wisdom.

Sociolinguists think language is an essential part of this universe and suggest languages be preserved, documented and promoted. There are more than 6,000 languages spoken in the world, of which only ten percent are said to be able to survive over a few decades. Researchers claim a language dies biweekly in the world today. Around 60 languages are spoken in Pakistan, and that’s excluding Urdu and English. Besides the national and official languages, the other languages of which Pakistanis are aware of are misnamed as ‘regional languages’ viz Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi and Balochi. Even these languages are not fully ‘public’, meaning that they are not taught to students nor are they incorporated in the media, which is an affective tool to preserve and spread a language.

Although there is some good news regarding Pashto and Sindhi, most Pakistanis do not know what other languages are spoken in different areas of the country. Even the otherwise well-informed literary figures and researchers do not know about these languages; and whenever they come under discussion at different forums the participants dismiss them altogether, saying, ‘Oh, these are but ‘dialects’. The reason behind this apathy is that these languages have no nationalist political parties supporting them, and those who speak them are not politically or socially well off enough to have a say in the affairs of the state. Nevertheless these factors do not make these languages less important. Many of them have histories as old as the history of Sanskrit in the Subcontinent.

Historical data reveals that over the centuries, invaders either killed or drove out indigenous people from the land they invaded to peripheral areas such as rock-locked valleys in mountains, which resulted in severing all contact with their tribes or clans. Over time, the common language or languages evolved into separate languages. Isolated from others who could understand their language and therefore preserve its original form, these people could not share a common power centre – consequently becoming alien to each other.

Demonised and demoralised politically, socially and economically these indigenous people were left as ‘speech communities’ only – with languages that they used for verbal communication only, not knowing how to read or write. Meanwhile, many ‘shifted’ to other languages completely and today nobody can determine the exact number of speakers of the indigenous languages. Anthropologists and linguists pinpoint a number of forces or processes that cause the extinction of a language. Change in language is a natural process where an old language evolves into a new language as in the case of ancient Greek and Old English.

‘Language murder’ or murder of language occurs when invading rulers impose their language or languages on those they rule, leading to the original language to become all but obsolete, colonially called vernacular. The other phenomenon that linguists discuss is ‘language suicide’ that happens when a particular language community does not want their language to be made public because they think their ‘language and culture’ are responsible for the miseries that they are afflicted with.

In reality, both language murder and suicide are the effects of the same cause. A community deems its language inappropriate, uncivilised, and responsible for their miseries because of the long held policies of the rulers towards them. This accelerates ‘language shift’, which is the most common cause of the death of a language. Today the ‘regional languages’ of Pakistan face the phenomenon of ‘language shift’ just as much as the ‘minority languages’ do. For example, the youth in urban Punjab cannot speak their mother tongue and feel happier speaking English or Urdu. Villagers who speak their native language are deemed rustic and consequently they also opt to learn the language their ‘modern’ counterparts are using.