|

The Urdu controversy

Tahir Kamran

English as official while Urdu and six others as the national language

The status of Urdu as an official as well as a national language has once again adorned the news bulletins and social media. Without any shadow of doubt, Urdu symbolises the richness of North Indian culture which is many centuries old. Urdu poetry can easily be ranked among the best in the world.

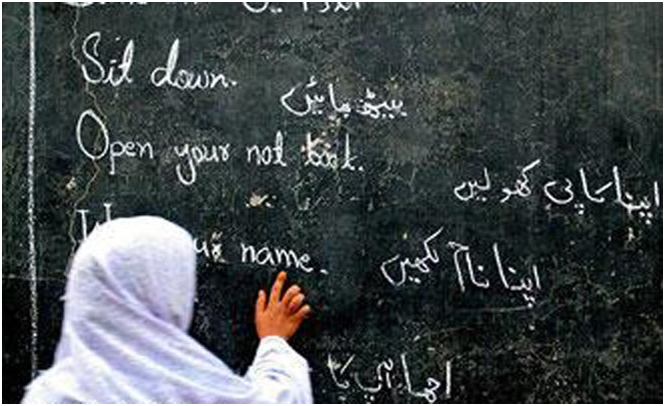

In Pakistan despite the fact that Urdu is the mother tongue of only 9.62 per cent of its residents, it still is the lingua franca in a country of diverse cultures and linguistic groups. Over the decades, Urdu has made noticeable progress in different genres like the short story, the novel and drama. However, Urdu prose still has a long way to go in its evolution into a mature instrument for the transmission of modern knowledge. It is, for example, rather comical to imagine Gray’s Anatomy rendered into Urdu.

The honourable prime minister of Pakistan has issued a directive exhorting state functionaries and legislators to use Urdu as a vehicle of expression while conducting the business of the state. The legislators must employ Urdu when making any policy statement. The overwhelming majority of our legislators already balk at using English simply because of their limited familiarity with the language. More importantly, however, the prime minister has also called for the huge corpus of legal texts and regulations to be rendered into Urdu so that the business of the state can be conducted in their light.

What this edict implies is that the spirit and essential substance of existing laws and regulations should remain as they are. Only the language is to be changed, as if this is an extremely simple and facile task. As a translator myself, I am fully cognisant of how translated text tends to betray an altogether different connotation from the original work. The Urdu textbook of economics for the Bachelors’ degree, for example, is far more inaccessible than its English version.

Any translated text is usually subject to conflicting interpretations. That problem becomes acute particularly when an English text is rendered into Urdu because the two languages hail from two different families, posing a vexing problem of appropriate synonyms to the translators. Consequently, when translating legal or theoretical material, the text becomes obfuscated in the extreme. But, by according seminal status to Urdu, the translation of major texts will merely be a peripheral hazard.

Our policy-makers are turning a blind eye to the gargantuan hazards of the political and socio-cultural fallout of this directive on our society. Some of them at least should take the trouble of reading Dr Tariq Rahman’s work so that they may have a bit of perspective on this particular issue.

As described above, Urdu serves as a lingua franca in socially diverse and culturally plural Pakistan. Nevertheless, for the past many decades, Urdu has been ethnicised to a considerable extent. In the mainland Sindh and central Balochishtan, its acceptability as a national language is highly improbable. In the districts of interior Sindh, Urdu is held to be the cultural signature of Mohajirs. Similarly one cannot be certain as to the sentiments in the Hazara Division in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, but in the Pashtu-speaking belt ethnic values are deeply entrenched and Pashtuns will certainly come forth with demands for government business to be conducted in their own language.

The point worth pondering is the ethnicisation of Urdu since the bloody 1972 riot in Karachi, which may be identified as the principal cause of the emergence of MQM. One must not lose sight of what happened in East Bengal in the early 1950s: a lot has been said and written about it, but nothing seems to have been learnt from that tragic episode of our history.

During the past 20 years Pakistan, for various reasons, has been excluded from the world stage in a systematic manner. On several occasions, it has been branded as the most dangerous place on earth. Former British High Commissioner to Pakistan Sir Nicholas Barrington, while conversing with me at Cambridge University, observed that Pakistan unfortunately is not adequately represented abroad in comparison to India. That is despite the fact that both countries are steeped in problems of corruption and religious extremism etc.

One of the many advantages that India has is its ability to represent itself through its diplomats but more so through its academics, among whom are a number of extremely significant scholars. Sir Nicholas said this while explaining to me the raison d’être of the foreign chairs, established in various Universities including Oxford and Cambridge. What I could read between the lines in his assertion was Pakistani academia’s limited familiarity with English.

In a scenario where Pakistan has virtually been politically ostracised, we need to get back into the mainstream of the international comity of nations. English can serve as a bridge in doing this. One hopes that the point is not trivialised by citing the examples of China, Japan and South Korea. Our case is markedly different from these countries with no (or very limited) colonial baggage.

Lastly, the sole use of Urdu at an official level will definitely give strength to the people on the ultra-right of the political spectrum. It is not very hard to conclude that Urdu has served the cause of religious extremism and those factions with sectarian tendencies. Historically speaking, Dar ul Ulum Deoband was the first institution which adopted Urdu as a medium of instruction. Afterwards, Islamic literature was mostly churned out in the same language. The Muslim middle class in 20th century India constituted of those who emerged from the liberal educational institutions with English as the medium of instruction, and also employed it as an instrument of social interaction, the case of Quaid-i-Azam himself corroborates that point. Thus the socio-cultural balance forged between tradition and modernity was struck through English only.

It is therefore argued that the Pakistani state and people should embrace English language, which must be retained as an official language. Objectively speaking, lately, Pakistan has produced more laureates in English language than even in Urdu, like Zulfiqar Ghose, Sara Suleri, Mohsin Hamid, Kamila Shamsi, Mohammed Hanif, Uzma Aslam Khan, Daniyal Mueenuddin, Muneeza Shamsi, Omar Shahid Hamid, Nadeem Aslam and Fatima Bhutto (One may include Bapsi Sidwa and Zia ud Din Sardar in that list too). I don’t know if we have so many acclaimed Urdu laureates in the contemporary era.

English does not deserved to be thrown out of window as an alien language. As far as the question of national language(s) is concerned, along with Urdu, six other languages (Sindhi, Punjabi, Pashto, Hindko, Balochi and Brahvi) ought to be given the status of national languages. It would certainly contribute towards forging a harmony which is desperately needed at this perilous hour.

Curtsey:The News, July 26, 2015

|