|

Options for Punjab’s progress

PUNJAB’S future can be portrayed in terms of several different scenarios for the economy’s growth in the period 2007 to 2020. I will work here with four of them. Which of these will get actually enacted will depend upon public policy choices made by the people who will walk the corridors of power in Islamabad and Lahore in the next few years.

The choices made will cover not only the field of economics but also the areas of politics and foreign affairs. According to the projections made for the four scenarios developed here the provincial GDP would increase at various multiples of the projected increase in population.

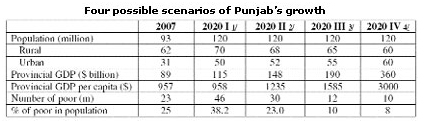

The least ambitious picture sees the province’s GDP increasing at a rate equal to twice the rate of population growth. Punjab’s population increase is expected to decline to about two per cent per annum over the next decade. Therefore, according to this scenario, GDP increases at a rate of only four per cent. (See the table for details.)

There will be an increase in per capita income of two per cent a year which, given the fairly unequal distribution of income, will not have a significant affect on the incidence of poverty .The provincial gross domestic product will grow by 66 per cent in the 13-year period between 2007--2020.

The number of poor will increase to 30 million and poverty will continue to be a major feature of life in the province. Most of the poor will live in the province’s large cities where they will suffer from the absence of several vital public services. While the level of literacy may increase beyond that reached in 2007, the poor will not have the skills required to find productive employment. With such a large concentration of the poor in large urban centres, the province would come under severe social and political stresses and strains.

The only contribution public policy needs to make to achieve this level of growth rate and sustain it over time is to ensure there are no serious disruptions to overall security in the province, that there is a reasonable amount of continuity in public policy, that the quality of education improves somewhat, that some provision is made for improving health care, and that some effort is made to remove the bottlenecks that have appeared in the availability of fiscal infrastructure. This is a business as usual scenario with no significant change in the structure of the economy.

The second scenario sees an increase in the provincial GDP equal to three times the rate of growth of population. In other words, provincial output will increase at a rate of six per cent a year, with GDP more than doubling in this period. This is very close to the scenario envisaged in the Punjab Economic Report, 2005. This report, prepared in association with the World Bank was based on the assumption that the economy would go through a significant structural change, particularly in the non-farm sectors. It assumed that the economy would be able to create one million jobs a year, a number large enough to absorb the new entrants in the workforce.

To maintain this level of increase in GDP – “maintain,” since this is the rate at which the provincial output increased in the period 1999-2007 – considerable amount of effort will have to be made in creating a pro-growth environment. The 2005 report made a large number of recommendations aimed at realising this growth rate. These focus in particular on improving the productivity of small and medium enterprises and improving the efficiency of the sector of agriculture.

There will be a much larger role for the private sector in the economy with the state confining its activity to mostly regulating private enterprise and making investments in improving physical and human capital. Public policy will also seek to address the problems created by some pick up in the rate of urbanisation. This scenario seems further increase in the proportion of the urban population living in the province’s major cities, in particular in Lahore and the industrial centres of central Punjab.

According to the third scenario, the provincial GDP will increase by eight per cent a year and income per head of the population will grow by six per cent per annum. The size of the provincial GDP will grow by more than two and a half times, increasing from the current $89 billion to $242 billion.

GDP per capita – a better measure of development – will more than double, from less than $1,000 in 2007 to more than $2,000 in 2020.

There will be dramatic effect on the level of poverty, with the proportion of the poor declining to just above eight per cent of the total population to only 10 million.

There will also be a significant change in the distribution of population. By 2020, one half of the 120 million people will live in urban areas. Lahore – counting its suburbs and satellite cities as parts of the city – will have a population of 15 million. It will be one of the world’s mega-cities.

Lahore’s own output could reach $50 billion with the city’s per capita income climbing to $3,300, more than 50 per cent higher than the projected provincial average.

The fourth and final scenario is the most ambitious one. It sees the economy growing at a rate of 10 per cent a year, five times the rate of increase in population.

This scenario will have the province reach the status of a middle income region with the provincial GDP at $360 billion and the income per capita at $3000.

Public policy will play a greater role in achieving this rate of growth. It will focus, in particular, on four aspects.

The main public policy initiative needed to achieve this rate of growth would be to open the economy to the world outside, in particular to India.

This will have a significant impact on the structure of the economy. The ratio of trade to GDP will increaser significantly and reach 50 per cent. In other words, Punjab alone will earn $180 billion in export earnings, most of it from trade with India.

Under this scenario, Punjab will also become the centre of transit trade, with goods and commodities passing through it to and from India, China, Central Asia and the Middle East.

To take full advantage of the opening to India and with the development of transit trade, the province will undertake a major improvement in its physical infrastructure: an intricate network of highways that will serve the traders in all countries with which Pakistan shares common borders.

The government would aid and encourage the development of the components of the service sector needed for handling trade and human traffic.

Some of the major cities and tourist sides will need to be improved to make them attractive for the Indians and people from the neighbouring countries.

The size of the urban areas will not increase beyond those envisaged under the third scenario.

That notwithstanding, the quality of life in the large cities – and to some extent also in the medium- sized and small cities – will improve with better provision of basic services to the population.

One interesting feature of the four scenarios is that the share of agriculture in GDP increases significantly in the last case. This will be the result of the larger proportion of trade in GDP and greater trade with India and the Middle East of high-value added agricultural products.

The share of modern services in the economy will also increase with a sizeable contribution made by the businesses associated with both international trade and transit trade.

In sum, appropriate set of government policies could turn Punjab into a middle-income province within less than a decade and a half.

Its economic transformation would pull along the rest of Pakistan towards a much higher rate of GDP growth than was the case even in the high growth years of the later part of the period of General Pervez Musharraf.

|