|

Punjabi Nationlaism-III (Next)

Punjabi Nationalism II

A Divided Punjab and the British Terrorist Legacy

A forgotten Punjab hero

A great deal of ruin in a nation

Capturing the Punjabi imagination

Demand for South Punjab

Not Speaking a Language that is Mine

MAULA JATT VS GENERAL ZIA

New pressure on Pakistan

I speak Punjabi (but my kids might not)

Ethnicity and Regional Aspirations In Pakistan

Jinnah and Punjab A Study of the Shams-ul-Hasan Collection

Ethnicity and provincialism in Pakistan What we don't normally hear or read

How Long Punjabi Nation Will Remain A Socially And Politically Depressed And Deprived Nation

A Divided Punjab and the British Terrorist Legacy

Author:Andre Vitchek

To kill 1.000 or more “niggers,” to borrow from the colorful, racist dictionary of Lloyd George, who was serving as British Prime Minister between 1916 and 1922, was never something that Western empires would feel ashamed of. For centuries, the British Kingdom was murdering merrily, all over Africa and the Middle East, as well as in the Punjab, Kerala, Gujarat, in fact all over the Sub-Continent. In London the acts of smashing unruly nations were considered as something “normal”, even praiseworthy. Commanders in charge of slaughtering thousands of people in the colonies were promoted, not demoted, and their statues have been decorating countless squares and government buildings.

Wherever I work on this planet, I see remnants of European colonial savagery.

This time I worked in the Indian state of Punjab. Here, an unrepentant bigot – General Dyer, killed 1579 people in 1919, in Amritsar, in just a few dreadful minutes.

A narrow passage to Jallianwala Bagh Garden, inside the old city of Amritsar…

This is where, on April 13 1919, thousands of people gathered, demanding release of two of their detained leaders, Dr. Satyapal and Dr. Saifuddin. The protest was peaceful. It was right before the day of Baisakhi, the main Sikh festival; and the pilgrims were pouring to the city in multitudes, from all corners of Punjab and Sub-Continent.

Peaceful or not, British Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer would not tolerate any demonstrations, any dissent, in the areas controlled by his troops. He decided to act, in order to teach the locals a lesson. There was no warning and no negotiations. General Dyer brought fifty Gurkha riflemen to a raised bank, and then ordered them to shoot at the crowd.

Bipan Chandra, a renowned Indian historian, wrote in his iconic work, “India’s Struggle for Independence”:

“On the orders of Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, the army fired on the crowd for ten minutes, directing their bullets largely towards the few open gates through which people were trying to run out. The figures released by the British government were 370 dead and 1200 wounded. Other sources place the number dead at well over 1000.”

Jallianwala Bagh is now a monument, a testament, a warning. There are bullet holes clearly marked in white, penetrating the walls of surrounding buildings. There is a well, where bodies of countless victims had fallen. Some people had chosen to jump, to escape the bullets.

There is a museum, containing historic documents: statements of defiance and spite from the officials of British Raj, as well as declarations of several maverick Indian figures, including Rabindranath Tagore, one of the greatest writers of India, who threw his knighthood back in the face of the British oppressors, after he learned about the massacre.

There are old black and white photos of Punjabi people tied to the polls, their buttocks exposed, being flagged by shorts-wearing British soldiers, who were apparently enjoying their heinous acts.

There is also a statement of General Dyer himself. It is chilling, arrogant and unapologetic statement:

“I fired and continued to fire until the crowd dispersed, and I consider this is the least amount of firing which would produce the necessary moral and widespread effect it was my duty to produce if I was to justify my action. If more troops had been at hand the casualties would have been greater in proportion. It was no longer a question of merely dispersing the crowd, but one of producing a sufficient moral effect from a military point of view not only on those who were present, but more especially throughout the Punjab. There could be no question of undue severity.”

I approached Ms. Garima Sahata, a Punjabi student, who did not hide her feelings towards the British Empire and the West:

“I feel ager, thinking what they had done to our people. I think it is important for us to come here and to see the remnants of the massacre. I still feel angry towards the British people, even now… but in a different way… They are not killing us the same way, as they used to in the past, but they are killing us nevertheless.”

The British Empire was actually based on enforcing full submission and obedience on its local subjects, in all corners of the world; it was based on fear and terror, on disinformation, propaganda, supremacist concepts, and on shameless collaboration of the local “elites”. “Law and order” was maintained by using torture and extra-judiciary executions, “divide and rule” strategies, and by building countless prisons and concentration camps.

The British Empire was above the law. All rights to punish “locals” were reserved. But British citizens were almost never punished for their horrendous crimes committed in foreign lands.

When the Nazis grabbed power in Germany, they immediately began enjoying a dedicating following from the elites in the United Kingdom. It is because British colonialism and German Nazism were in essence not too different from each other.

Today’s Western Empire is clearly following its predecessor. Not much has changed. Technology improved, that is about all.

Standing at the monument of colonial carnage in Punjab, I recalled dozens of horrific crimes of the British Empire, committed all over the world:

I thought about those concentration camps in Africa, and about the stations where slaves who were first hunted down like animals were shackled and beaten, then put on boats and forced to undergo voyages to the “new world” that most of them never managed to survive. I thought about murder, torture, flogging, raping women and men, destruction of entire countries, tribes and families.

In Kenya, I was shown a British prison for resistance cadres, which was surrounded by wilderness and dangerous animals. This is where the leaders of local rebellions were jailed, tortured and exterminated.

In Uganda, I was told stories about how British colonizers used to humiliate local people and break their pride: in the villages, they would hunt down the tallest and the strongest man; they would shackled him, beat him up, and then the British officer would rape him, sodomize him in public, so there would be no doubts left of who was in charge.

In the Middle East, people still remember those savage chemical bombings of the “locals”, the extermination of entire tribes. Winston Churchill made it clear, on several occasions: “I do not understand the squeamishness about the use of gas,” he told the House of Commons during an address in the autumn of 1937. “I am strongly in favour of using poisonous gas against uncivilised tribes.”

In Malaya, as the Japanese were approaching, British soldiers were chaining locals to the cannons, forcing them to fight and die.

Wherever the British Empire, or any other European empire, grabbed control over the territory – in Africa, Caribbean, the Middle East, Asia, in Sub-Continent, Oceania – horror and brutality reigned.

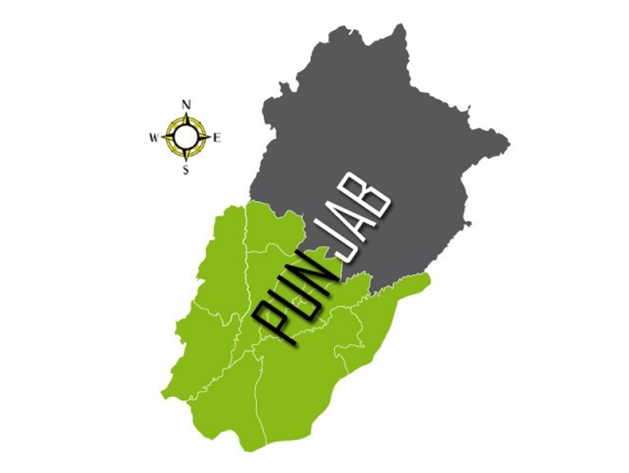

Now, Punjab is divided, because that old “divide and rule” scheme was applied here meticulously, as it was almost everywhere at the Sub-Continent.

The British never really left: they live in the minds of Indian elites.

Punjab suffered terribly during the Partition, and later, too, from brutality of the Indian state. In fact, almost entire India is now suffering, unable to shake off those racist, religious and social prejudices.

Delhi behaves like a colonialist master in Kashmir (where it is committing one of the most brutal genocides on earth), the Northeast and in several other areas. Indian elites are as ruthless and barbaric as were the British colonizers; the power system remained almost intact.

The Brits triggered countless famines all over India, killing dozens of millions. To them, Indian people were not humans. When Churchill was begged to send food to Bengal that was ravished by famine in 1943, he replied that it was their own fault for “breeding like rabbits” and that the plague was “merrily” culling the population. At least 3 million died.

It goes without saying that the Indian elites, disciples and admirers of British Raj, are treating its people with similar spite.

Only 30 kilometers from Amritsar, one of the most grotesque events on earth takes place: “Lowering of the Flag” on the Indian/Pakistani border. Here, what is often described as the perfectly choreographed expression of hate, takes place in front of thousands of visitors from both countries.

Wagah Border has even tribunes built to accommodate aggressive spectators. It is everyday:

“Death to Pakistan!

Long Live India!”

“Death to India!

Long live Pakistan!”

“Hindustaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaan Zindabad!!!!!!” They shout here, “Long Live India”, and those endless spasms are immediately followed by barks glorifying India and insulting Pakistan.

Border guards, male and female, are then performing short marches, at a tremendously aggressive and fast pace, towards the border gate. The public, sick from the murderous heat and the fascist, nationalist idiocy, speeches and shouts, is roaring.

The seeds sown by the British Raj have been inherited by several successive states of the Sub-Continent. They are now growing into a tremendous toxic and murderous insanity. Instead of turning against the murderous elites, the poor majority is yelling nationalist slogans.

Everything here is deeply connected: the colonial torture, the post-colonial genocides, the prostitution of the local elites, who are selling themselves to the rulers of the world, the over-militarization, the institutionalized spite for the poor and for the lower castes and classes.

Confusion is omnipresent. Words and terminology have lost their meanings. Dust, injustice, pain and insecurity are everywhere.

Anyone who claims that colonialism is dead is either a liar or a madman.

And if this – the direct result of colonialism – is “democracy”, then we should all, immediately, take a bus in the opposite direction!

Andre Vltchek is philosopher, novelist, filmmaker and investigative journalist, he’s a creator of Vltchek’s World an a dedicated Twitter user, especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

First appeared:http://journal-neo.org/2015/05/01/a-divided-punjab-and-the-british-terrorist-legacy/

Curtsey:www. journal-neo.org 01/05

Off the Shelf

A forgotten Punjab hero

V.N. Datta

Dr Satyapal: The Hero of Freedom Movement in the Punjab

by Shailja Goyal. PBG Publications, Ludhiana. Pages 271.

HISTORY is nothing but the biography of men and women. However, this should not mean that biography is the story of kings and queens and of their adventures and romances. It has a wider dimension. Lytton Strachey was the first biographer who gave a new direction to the writing of biography by highlighting negative features of his portraits that he drew with ardour and flashing wit. He looked at both sides of the coin.

It is regrettable, indeed, that the biographies of some of the Punjab political leaders who played a vital role in our freedom struggle are few. Though the political activities of Lala Lajpat Rai and Saif-ud-Din Kitchlew (see his writings edited by his son, Taufiq Kitchlew) have been widely covered, Lala Harkishan Lal, Rambhaj Datta, Master Tara Singh, Sohan Singh Josh and Abdul Ghani Dar still await the historian. It is highly creditable that a senior lecturer of the History Department of Lala Lajpat Rai DAV College, Jagraon, Shailja Goyal, has brought out a biography of one of the most prominent political leaders hitherto forgotten. While facing enormous difficulties, he fought with passionate fervour for the emancipation of his country from the fetters of the British rule.

This work is an expanded version of a Ph.D. thesis submitted to Punjab University, Patiala. It opens with a synoptic introduction, covering the period from the end of the 19th century to the First World War, and analyses the social, economic and political conditions in Punjab, culminating in the anti-Rowlatt agitation, which the British took as a major challenge to their authority. In the second chapter, the author traces the various social and intellectual influences that had shaped Dr Satyapal’s political outlook, especially the Arya Samaj and Mahatma Gandhi’s idea of independence of the country.

There was nothing narrow or sectarian in his outlook — he valued greatly the freedom of thought and conscience, and integrity of character.

After obtaining an MBBS degree from King Medical College, Lahore, Dr Satyapal set up his clinic in Amritsar. He started his practice as a surgeon, but his heart lay elsewhere. When the occasion came, he rose to it, sacrificing his career and plunging into the whirlwind of anti-Rowlatt agitation. There was no turning back. Satyapal and Kitchlew became the "darlings" of the people of Amritsar, and their arrest on April 10, 1919, by the nervous, panicky Deputy Commissioner, Henry Irving, brought tears to many eyes and saddened many hearts. Their arrest kindled widespread political agitation in the province.

According to the author, Satyapal took his arrest lightly and never lost his sense of humour

which is evident in his letter addressed to his father (p. 69). While covering the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, the author accepts the death toll figure of 1,000 cited by Madan Mohan Malaviya. I think this figure is exaggerated. A recent research has shown that the number of victims did not exceed 750. Shailja Goyal rightly writes that due to the anti-Rowlatt Act agitation, "Amritsar became a pilgrimage for the nationalists." Satyapal and Kitchlew were released from jail on the eve of the Congress session in Jallianwala Bagh on December 26, 1919, where they were welcomed with thunderous applause by the delegates and audience.

The author maintains that there was hardly a political activity connected with the freedom movement in which Satyapal did not enthusiastically participate. For instance, he participated in the Non-Cooperation Movement, the agitation against the Simon Commission and Civil Disobedience Movement, and suffered bravely the brunt of government oppression and imprisonment. While he languished in jail, his family suffered greatly due to financial strains. This work brings Satyapal’s participation in the Congress mass movement from 1919-38. Due to his differences with the Congress leadership, he ultimately resigned from the party, much to his chagrin, on July 12, 1941, and applied for the membership of the Indian Medical Service to help the Red Cross during the First World War. He rejoined the Congress in 1953. He was also Speaker of the Vidhan Sabha.

Shailja Goyal takes up two significant issues, which are generally neglected by scholars.

First, the author discusses the Muslim participation in nationalist movement. Second, she engages with the theme of Muslim separatism from the mainstream of Indian nationalism. Offering cogent reasons for the rise of the communal temperature in Punjab, she raises the question as to why the nationalist movement in Punjab did not reflect the vitality and strength as compared with other provinces. I think the brilliant leadership provided by Fazli Husain and Chhotu Ram, to a large extent, stemmed the rising tide of nationalism.

This is one of the few works in which an attempt has been made to show how factionalism within the Congress ranks in Punjab weakened the forces of nationalism and the possibility of a united front against the British government. Was this factionalism a product of clash of personalities or ideological one? How a first-rank Punjabi political leader like Satyapal was forced to quit the Congress? Satyapal attributed his departure from the Congress primarily to Mahatma Gandhi’s "dictatorial" attitude in the working of the party. Subash Chandra Bose and Aurobindo Ghosh too nurtured similar grievances.

Based on extensive source material, the biography provides the portrait of a secular patriot. It also reconstructs the times and forces that shaped his life history. Shailja Goyal’s book is a significant contribution to our understanding of one of the most crucial periods of Punjab’s nationalist upsurge. She brings to light the story of a neglected Punjabi nationalist who played an outstanding role in India’s struggle for freedom.

|

Curtsey:www.tribuneindia.com Sunday, March 7, 2004

Pakistan

A great deal of ruin in a nation

Why Islam took a violent and intolerant turn in Pakistan, and where it might lead

“TYPICAL Blackwater operative,” says a senior military officer, gesturing towards a muscular Westerner with a shaven head and tattoos, striding through the lobby of Islamabad's Marriott Hotel. Pakistanis believe their country is thick with Americans working for private security companies contracted to the Central Intelligence Agency; and indeed, the physique of some of the guests at the Marriott hardly suggests desk-bound jobs.

Pakistan is not a country for those of a nervous disposition. Even the Marriott lacks the comforting familiarity of the standard international hotel, for the place was blown up in 2008 by a lorry loaded with explosives. The main entrance is no longer accessible from the road; guards check under the bonnets of approaching cars, and guests are dropped off at a screening centre a long walk away.

Some 30,000 people have been killed in the past four years in terrorism, sectarianism and army attacks on the terrorists. The number of attacks in Pakistan's heartland is on the rise, and Pakistani terrorists have gone global in their ambitions. This year there have been unprecedented displays of fundamentalist religious and anti-Western feeling. All this might be expected in Somalia or Yemen, but not in a country of great sophistication which boasts an elite educated at Oxbridge and the Ivy League, which produces brilliant novelists, artists and scientists, and is armed with nuclear weapons.

Demonstrations in support of the murderer of Salman Taseer, the governor of Punjab, in January, startled and horrified Pakistan's liberals. Mr Taseer was killed by his guard, Malik Mumtaz Qadri, who objected to his boss's campaign to reform the country's strict blasphemy law. Some suggest that the demonstrations were whipped up by the opposition to frighten the Pakistan People's Party (PPP) government, since Mr Taseer was a member of the party. Others say the army encouraged them, because it likes to remind the Americans of the seriousness of the fundamentalist threat. But conversations with Lahoris playing Sunday cricket in the park beside the Badshahi mosque suggest that the demonstrations expressed the feelings of many. “We are all angry about these things,” says Gul Sher, a goldsmith, of Mr Taseer's campaign to reform the law on blasphemy. “God gave Qadri the courage to do something about it.”

Pakistani liberals have always taken comfort from the fundamentalists' poor showing in elections and the tolerant, Sufi version of Islam traditionally prevalent in rural Pakistan. But polling by the Pew Research Centre suggests that Pakistanis take a hard line on religious matters these days (see chart 1). It may be that they always did, and that the elite failed to notice. It may be that urbanisation and the growing influence of hard-line Wahhabi-style Islam have widened the gap between the liberal elite and the rest. “The Pakistani elites have lived in a kind of cocoon,” says Salman Raja, a Lahore lawyer. “They go to Aitchison College [in Lahore]. They go abroad to university…A lot of us are asking ourselves whether this country has changed while our backs were turned.”

The response to another death suggests that the hostility towards Mr Taseer may not have been only about religion. Two months later Shahbaz Bhatti, the minister for minorities, was murdered for the same reason. Yet his killing did not trigger jubilation. Mr Taseer's offence may have been compounded by the widespread perception that he, like most of the elite, was Westernised. His mother was British, he held parties at his house, and he posted photos on the internet of his children doing normal Western teenage things—swimming and laughing with the opposite sex—that caused a scandal in Pakistan.

The West in general, and America in particular, are unpopular. It was not always thus. Before the Soviet Union left Afghanistan, around a third of Pakistanis regarded Americans as untrustworthy. Since then, a fairly stable two-thirds have done so. The latest poll on the matter (see chart 1) suggests that Pakistanis see America as more of a threat to their country than India or the Pakistani Taliban. It was carried out in 2009, but anecdotal evidence confirms that the views have not changed. “America is behind all of our troubles,” says Mohammed Shafiq, a street-hawker. That may be because America is thought to have embroiled Pakistan in a war which has caused the surge in terrorism; or because many Pakistanis, including senior army officers, genuinely believe that the bombings are being carried out by America in order to destabilise Pakistan, after which it will grab its nuclear weapons.

Four horsemen

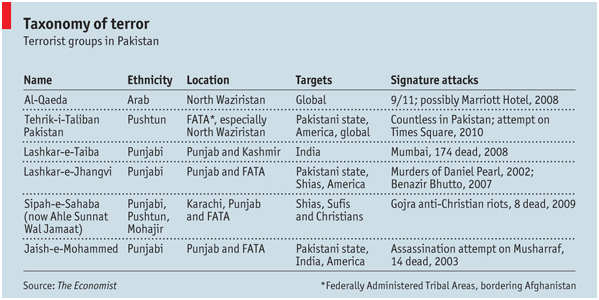

From the complex web of factors that have fostered intolerance and violence in Pakistan, it is possible to disentangle four main strands. The first is Pakistan's strategic position. Big powers have long competed for control of the area between Russia and the Arabian Gulf, and the unresolved tensions with India have dogged the country since its birth in 1947. Nor has Pakistan tried to keep out of its neighbours' affairs. It was America's enthusiastic ally in the war to eject the Soviet Union from Afghanistan in the 1980s, which it sold to its people as a jihad. “We used religion as an instrument of change and we are still paying the price,” says General Mahmud Ali Durrani, former national security adviser and ambassador to Washington. Pakistan helped create the Taliban in the 1990s to try to exert some control over Afghanistan. And with much trepidation on the part of its leaders, and reluctance on the part of its people, it has supported America in its war against the Taliban over the past decade.

By trying to destabilise India, Pakistan has undermined its own stability. “When the Soviets went away,” says a senior military officer, “we had a very large number of battle-hardened people with nothing to do. They were redirected towards India. The ISI [Inter-Services Intelligence, the main military-intelligence agency] was controlling them…20:20 hindsight is very good, but this decision was perhaps wrong.” According to the officer, after al-Qaeda's attacks against America on September 11th 2001 the army decided to wind down the policy. “We started taking them out. But many of them said, ‘Nothing doing.' They had contact with people in the Afghan jihad, and they joined those people again.” Because the Pakistanis were helping the Americans in their fight against the Afghan Taliban, the Pakistani jihadisturned their fury on the government.

The second strand is the unresolved question of Islam's role in the nation. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan's founder, made it clear that he thought Pakistan should be a country for Muslims, not an Islamic country. But since then, according to General Durrani, “Every government that has failed to deliver has used Islam as a crutch.” Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, for example, though fond of a drink himself, banned alcohol. Zia ul Haq, his successor, tried to legitimise his military coup by pledging to Islamise the country.

The relationship between religion and the state is not an abstruse question of political philosophy. A treatise on the Pakistani constitution published in 2009 by Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda's number two (who is believed to be in North Waziristan), argues that the Pakistani state is illegitimate and must be destroyed. This tract is widely read in themadrassas from which the terrorist groups draw their recruits. Its popularity exercises Qazi Hussein Ahmed, the grand old man of the Jamaat-e-Islami, the most fundamentalist of the political parties, for the Jamaat works within the state, not against it. He argues that Pakistan's failure to adopt an Islamist constitution “has given the Taliban and such extremist elements a pretext: they say the government will not bow to demands made by democratic means, so they are resorting to violent means.”

The third strand is the uselessness of the government. Democracy in Pakistan has been subverted by patronage. Parliament is dominated by the big landowning families, who think their job is to provide for the tribes and clans who vote for them. Except for the Jamaat-e-Islami, parties have nothing to do with ideology. The two main ones are family assets—the Bhuttos own the PPP, and the Sharifs (Nawaz Sharif, the former and probably future prime minister, and his brother Shahbaz, chief minister of Punjab) own the Pakistan Muslim League (N). The consequence is dire political leadership of the sort shown by Asif Ali Zardari, who is president only because he married into the Bhutto dynasty. When Pakistan desperately needed a courageous political gesture in response to the murders of the governor and minister, the president failed even to attend their funerals.

Pakistan's rotten governance shows up in its growth rates (see chart 2). In a decade during which most of Asia has leapt ahead, Pakistan has lagged behind. Female literacy, crucial as both an indicator of development and a determinant of future prosperity, is stuck at 40%. In India, which was at a similar level 20 years ago, the figure is now over half. In East Asia it is more like nine out of ten.

Given the government's failings, it is hardly surprising if Pakistanis take a dim view of democracy. In a recent Pew poll of seven Muslim countries they were the least enthusiastic, with 42% regarding it as the best form of government—though, since the country has spent longer under military than under democratic rule, the army is at least as culpable.

The armed forces' dominance is the fourth strand. Tensions with India mean that the army has always absorbed a disproportionate share of the government's budget. Being so well-resourced, the army is one of the few institutions in the country that works well. So when civilian politicians get them into a hole, Pakistanis look to the military men to dig them out again. They usually oblige.

Terrorism is strengthening the army further. In 2009 it drove terrorists out of Swat and South Waziristan, and it is now running those areas. Last year its budget allocation leapt by 17%. Nor are the demands on the armed forces likely to shrink. Although overall numbers of attacks are down from a peak in 2009, they have spread from the tribal areas and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), along the border with Afghanistan, to the heartland. Last year saw an uptick in attacks on government, military and economic targets in Punjab and Karachi, the capital of Sindh province. Since then, security has been stepped up; and with the usual targets—international hotels, government buildings and military installations—surrounded by armed men and concrete barriers, terrorists are increasingly attacking soft targets where civilians congregate, such as mosques and markets.

Exporting terror

Pakistani terrorism has also gone global. The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP, or Pakistani Taliban), announced when it was formed in 2007 that it aimed to attack the Pakistani state, impose sharia law on the country and resist NATO forces in Afghanistan. But last year Qari Mehsud, now dead but thought to be a cousin of the leader, Hakimullah Mehsud, who was in charge of the group's suicide squad, announced that American cities would be targeted in revenge for drone attacks in tribal areas. That policy was apparently taken up by Faisal Shahzad, a Pakistan-born naturalised American who tried to blow up New York's Times Square last year.

Pakistan's new face? Pakistan's new face?

That prompted an increase in American pressure on the army to attack terrorists in North Waziristan. The army is resisting. The Americans suspect that it wants to protect Afghan Taliban there. The Pakistani army says it is just overstretched.

“We are still in South Waziristan,” insists a senior security officer. “We are holding the area. We are starting a resettlement process, building roads and dams. We need to keep the settled areas free of terrorists. It is not a matter of intent that we are not going into North Waziristan. It is a matter of capacity.”

The growth in terrorism in Punjab poses another problem for the army. “What we see in the border areas is an insurgency,” says the officer. “The military is there to do counter-insurgency. What you see in the cities is terrorism. This is the job of the law-enforcement agencies.” But the police and the courts are not doing their job. One suspected terrorist, for instance, a founder member of the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, was charged with 70 murders, almost all of them Shias. He was found not guilty of any of them for lack of evidence. In 2009 the ISI kidnapped 11 suspected terrorists from a jail in Punjab, because it feared that the courts were about to set them free.

So where does this lead? Not to a terrorist march on the capital. Excitable Western headlines a couple of years ago saying that the Taliban were “60 miles from Islamabad” were misleading: first because the terrorists are not an army on the march, and second because they are not going to take control of densely populated, industrialised, urban Punjab the way they took control of parts of the wild, mountainous frontier areas and KPK.

Yet even though they will not overthrow the Pakistani state, the combination of a small number of terrorists and a great deal of intolerance is changing it. Liberals, Christians, Ahmadis and Shias are nervous. People are beginning to watch their words in public. The rich among those target groups are talking about going abroad. The country is already very different from the one Jinnah aspired to build.

The future would look brighter if there were much resistance to the extremists from political leaders. But, because of either fear or opportunism, there isn't. The failure of virtually the entire political establishment to stand up for Mr Taseer suggests fear; the electioneering tour that the law minister of Punjab took with a leader of Sipah-e-Sahaba last year suggests opportunism. “The Punjab government is hobnobbing with the terrorists,” says the security officer. “This is part of the problem.” A state increasingly under the influence of extremists is not a pleasant idea.

It may come out all right. After all, Pakistan has been in decline for many years, and has not tumbled into the abyss. But countries tend to crumble slowly. As Adam Smith said, “There is a great deal of ruin in a nation.” The process could be reversed; but for that to happen, somebody in power would have to try.

Curtsey:www.Economist.com From the print edition: Asia

Mar 31st 2011 | ISLAMABAD AND LAHORE

Read the original article at source link: http://www.economist.com/node/18488344

Capturing the Punjabi imagination: drones and “the noble savage”

By Myra MacDonald

Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid may have captured something rather interesting in his short story published this month by The Guardian. And it is not as obvious as it looks. Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid may have captured something rather interesting in his short story published this month by The Guardian. And it is not as obvious as it looks.

In “Terminator: Attack of the Drone”, Hamid imagines life in Pakistan’s tribal areas bordering Afghanistan under constant attack from U.S. drone bombings. His narrator is one of two boys who go out one night to try to attack a drone.

”The machines are huntin’ tonight,” the narrator says. “There ain’t many of us left. Humans I mean. Most people who could do already escaped. Or tried to escape anyways. I don’t know what happened to ‘em. But we couldn’t. Ma lost her leg to a landmine and can’t walk. Sometimes she gets outside the cabin with a stick. Mostly she stays in and crawls. The girls do the work. I’m the man now.

“Pa’s gone. The machines got him. I didn’t see it happen but my uncle came back for me. Took me to see Pa gettin’ buried in the ground. There wasn’t anythin’ of Pa I could see that let me know it was Pa. When the machines get you there ain’t much left. Just gristle mixed with rocks, covered in dust.”

It is powerful stuff, told in the language of a black American slave in the style of Toni Morrison’s “Beloved”. It vividly captures the terror inspired by drones, and the helplessness of the people who live in the tribal areas. But is it true? And does it matter?

In a discussion on Twitter, literary critic Faiza S. Khan, who tweets @BhopalHouse, argued that the story should be judged as a work of fiction rather than taken as reportage. A fair point. But what if we turn this around and consider the story as reportage, not of the tribal areas and the drones, but of the way these are imagined in Pakistan’s Punjabi heartland? As a writer who spends part of his time in Lahore, capital of Punjab, Hamid can be considered representative of at least part of that Punjabi imagination.

We will return to the short story later, but first step back a bit and consider that the narrative gaining traction, at least in urban Punjab, is that the people of the tribal areas have been radicalised by American drone attacks. Pakistan’s rising political star, Imran Khan, attracted tens of thousands to a rally in Lahore last month with a version of this narrative. Stop the drones, and the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), or Pakistani Taliban, can be engaged in peace talks to end a wave of bombings across Pakistan.

The simplicity of this narrative is beguiling. At a stroke it taps into the anti-Americanism prevalent in Pakistan and also promises peace. Yet it is incredibly problematic. Bear with me – this is not a defence of drones per se. The use of “machines” to fight a war is disturbing, as indeed is the use of snipers in their capacity for personalised targetting by an unseen hand. Emotionally, I would be far more scared of drones and snipers than I would be of artillery and airstrikes, even if I knew the latter two were more likely to kill me. And nor is it a defence of the way the United States has fought its war in Afghanistan - the risks of the Afghan war going wrong have been obvious from the start to anyone with a knowledge of history. But those are different subjects. This is about how the drone campaign is perceived in mainland Pakistan, and perhaps particularly in Punjab.

The first problem with the narrative is that it slides over the fact that radicalisation in the tribal areas (and Pakistan as a whole) began long before the U.S. drone campaign. Many ascribe it to Pakistani support for the United States in backing the jihad against the Soviet Union after the Russians invaded Afghanistan in 1979. I might go further back, perhaps to the 1973 oil boom when a disproportionate number of Pashtun from the tribal areas went to seek work in the Gulf . The results were twofold – the migrant workers were exposed to the Wahhabi puritanical Saudi Arabian tradition of Islam, and the remittances they sent home upset the traditional balance of power in the local economy. I could go back even further, to the origins of the Pakistani state in 1947 and its use of Islam as a unifying force to counter ethnic nationalism, including Pashtun nationalism. In short – it is complicated. Stopping drones may or may not be a moral imperative, depending on your perspective. But let’s not be fooled into thinking that in itself, it will bring peace.

Secondly, the narrative on drone attacks takes at face value assertions that they cause high numbers of civilian casualties. The Americans say they are precise; their critics say they are lying; the rest of us simply don’t, and can’t, know the truth. With little independent reporting on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), we can’t possibly verify whether the claims of civilian casualties are accurate. We don’t know for sure the numbers of the dead, let alone whether among those dead were Taliban foot soldiers who are also civilians.

What I have noticed however, is that at least some among the Pashtun intelligentsia say the drone strikes are precise, and that opposition to them increases the further away you get from the tribal areas. Earlier this year, a senior Pakistani military officer was quoted as saying that ”a majority of those eliminated are terrorists, including foreign terrorist elements”. Writer and academic Farhat Taj has taken this argument further by saying that people actually prefer drone strikes to living in fear of the Taliban and their foreign allies.

Now I don’t know the truth. I have been to the tribal areas only once, on a one-day army-supervised trip to Bajaur. Incidentally, I was struck by how far the landscape differed from my own Kiplingesque imaginings of “the Frontier”. In Bajaur, I saw agricultural prosperity, neatly laid out fields, and mountains which in relative terms (ie compared to Siachen, the Karakoram and even the barren mountains of Scotland) seemed unexpectedly tame. I gather other parts of FATA are wilder, but that Bajaur trip was a lesson for me in how far my imagination (no doubt heavily influenced by colonial literature) was very different from reality. Many Pakistanis never get a chance to visit FATA at all – and so it remains in the Pakistani heartland as much of an imagined frontier as it was under the Raj.

So to get back to the drones, let’s for a moment take the prevalent view that Pakistan is fighting “America’s war” out of the discussion and consider what the people of FATA themselves think about drone attacks and peace talks with the Taliban. As the people who suffer most at the hands of the Pakistani Taliban, their views - at least from a moral point of view – should predominate in any Pakistani discourse which set itself up as idealistic. What do they say?

This brings me to the most problematic part of the narrative, and loops back into Hamid’s short story. In the “stop the drones, win the peace argument”, the people of FATA are crucially assumed not to be able to speak for themselves. They are frozen in time in an idealised village life, people who will revert to their ancient traditions as soon as the drones and the Afghan war ends, as though the last 60 years of history never happened. As though not not one of them had ever got on a plane, worked in the Gulf, or migrated to Karachi.

Look at how they are portrayed in Hamid’s story (though since I have not asked him, I will concede this may have been an intentional parody of the way the people of FATA are often viewed).

In his story, our characters have no ability to grasp the big world events that have brought the machines to their land. They speak in the language of black American slaves. The narrator’s mother is compared to an animal, “snorin’ like an old brown bear after a dogfight”. Their primitiveness is underlined by the sexualisation of the weapon assembled by the two boys to attack the drone: ”We put the he-piece in the she-piece”.

They are reduced to the cipher of “the noble savage“.

It is true that the people of FATA do not tend to speak for themselves. But given the scale of bombings and assassinations, fear seems to be a more likely explanation than an inability to articulate their thoughts.

And it is also true that they are not even proper citizens. Rather they are subject to the Frontier Crimes Regulation – a draconian colonial-era law which makes them liable to collective punishment, and which is only slowly being reformed by the Pakistani government. The eventual abolition of the FCR, the incorporation of FATA into Pakistan, and other reforms meantto decentralise and accommodate Pakistan’s different ethnic groups, would arguably be far more effective in the long run in allowing the country’s Punjabi heartland to make peace with the Pashtun in the tribal areas, more even than ending drone strikes.

You will find people who argue you can do both – abolish the FCR and end drone strikes. But how can you tell? How do you make peace with a particular group and work out what suits them best, unless they are represented politically? (Holding peace talks with the Pakistani Taliban is not the same.)

Now reread Hamid’s piece and consider the gap between the characters imagined in his short story, and a people with full citizenship rights and political representation. As Fazia S. Khan said, judge it as a work of fiction. But as a window into the Punjabi imagination, it may also have its uses as a political document.

Reported for Reuters on France, Egypt, the European Union and South Asia, and author of "Heights of Madness", a book about the Siachen war between India and Pakistan. Now based in London.

Any opinions expressed here are the author's own.

Curtsey:blogs.reuters.com: November 13, 2011

Source Link: http://blogs.reuters.com/pakistan/2011/11/13/capturing-the-punjabi-imagination-drones-and-the-noble-savage/

Demand for South Punjab

By Abdul Manan

PML-N does not disagree on the creation of new provinces, but demands it be created on an “administrative basis” only.

LAHORE: While the demand for a separate South Punjab province has been making the rounds at discussions, editorials, and other forums for decades, it gained political traction in February 2011 after the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) parted ways with the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) provincial government in the Punjab.

Between 2008 and 2011, when the PPP sat on treasury benches in the Punjab Assembly, it sided with the PML-N on knocking out resolutions pertaining to South Punjab province. PML-Q’s MPA Mohsin Leghari submitted tens of resolutions, in almost every session, but none were supported by the PPP.

After the fallout, PPP’s Co-Chairman, President Asif Ali Zardari, asked the party’s manifesto committee to prepare recommendations for a new province. The committee has held only one meeting since 2011, but never discussed the issue of South Punjab.

Gaining traction

Before being taken up by the leading parties, the PPP and the PML-N, the issue also lacked electoral support.

Leaders, like the Pakistan Seraiki Party’s President Barrister Taj Muhammad Langah, who have been most vocal about a Seraiki or South Punjab province, have never been elected to parliament or provincial assemblies.

The tide, however, turned around after the PML-N wrapped up the local government system in 2008, introduced by former president Pervez Musharraf under his regime.

As authority centered back in Lahore, the demand for South Punjab went from drawing rooms to the street.

Budget figures

At the 2010 budget speech in the Punjab Assembly, lawmakers from South Punjab protested on the floor of the house over the allocation of “Rs5 billion” for South Punjab.

Terming the amount “equivalent to Zakat,” the lawmakers lashed out at Rs21 billion spent on Raiwind road that leads to the Sharifs’ residence outside Lahore.

Chairman Planning Department of Punjab, however, refuted the claim.

Giving official figures to The Express Tribune, the chairman said the PML-N government increased the allocation of development budget to South Punjab from Rs22 billion in 2007-08, or 15% of total development allocation in the Punjab, to Rs70 billion in 2011-12, or 32% of total allocation.

The allocation, however, does not necessarily translate into disbursements which may be far lower.

Rhetoric versus action

The PML-N says the resolution in National Assembly is an attempt to deflect pressure on the government following conviction of Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani in a contempt case.

Analysts second that, saying the resolution is merely a political gimmick that attempts to cash in on public support on the issue in , what is widely perceived to be, an election year.

Caving out a new province will require a bill, not a resolution, they say, adding that a resolution has no legal weight and does not make South Punjab imperative. Since a new province would require amending the Constitution, the PPP, if it is serious about South Punjab, should have moved a bill.

What is the process?

The process for amendment to the Constitution, which is essentially what a new province would entail, is laid out in Article 239 of the Constitution.

A bill has to be moved in either houses of parliament, National Assembly or Senate, and has to pass with a two-thirds majority in both. Any regular bill would then be sent to the president for endorsement but sub article 4 adds an extra provision for this case, which states: A bill to amend the Constitution which would have the effect of altering the limits of a province shall not be presented to the president for assent unless it has been passed by the provincial assembly of that province by the votes of not less than two-thirds of its total membership.

Few months ago, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement submitted a bill to remove the aforementioned clause. The bill, however, is pending in National Assembly secretariat and has not been entertained.

South Punjab, therefore, needs the assent of both – the PPP and the PML-N – if it has to become a reality under the current Constitution, and before the next election.

PML-N’s counter-proposals

The PML-N does not disagree on the creation of new provinces, but demands that they should be created on an “administrative basis” only.

The party, in its policy presented last year, has called for a commission, like the States Reorganisation Commission constituted in India in 1953, which should form new provinces after detailed study.

According to the PML-N’s manifesto committee, the party has plans for 13 new provinces in Pakistan; and while not much progress was seen on that front, the party was jolted into action on Friday.

Hours after PPP’s resolution was passed by the National Assembly, the PML-N submitted a counter resolution to the NA secretariat, calling for the creation of not one but four provinces – South Punjab, Bahawalpur, Fata and Hazara.

Sources in the party, however, say the PML-N’s stance on a prospective ‘Bahawalpur’ province is a political attempt to counter PPP’s demand of a ‘South Punjab’ province.

Bahawalpur versus South Punjab

While the debate on southern Punjab, until recently, focused on South Punjab versus Bahawalpur, PML-N’s resolution submitted on Friday now calls for creation of both.

The party is not the only one calling for a Bahawalpur province though.

Former information minister Senator Muhammad Ali Durrani, a leading figure in the movement for a separate Bahawalpur province, has demanded that the former princely state be given a provincial status.

It is the constitutional right of the people of Bahawalpur to have their own province, just like it is the right of the people of DI Khan and Multan to have their own province, Durrani said in a statement on Thursday.

Any effort to pitch the people of Bahawalpur against the people of DI Khan and Multan will fail, he added.

PML-Functional Punjab President Makhdoom Ahmad Mehmood has also demanded that Bahawalpur should be restored as a separate province, instead of inducting it into a Seraiki or South Punjab province.

Hazara province

Following through on its counter-proposal submitted to the NA secretariat on Friday, the PML-N submitted a resolution in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Assembly Secretariat, calling for forming the Hazara division a separate province. The resolution, filed on Friday, is signed by six lawmakers .

“Once it is carved into a new province, the revenue generated [through its resources] will be used on this region,” Muhammad Javed Abbasi told reporters. “It is very difficult to administer this division from Peshawar.”

The resolution states that the Hazara division is gifted with natural resources but unjust treatment by successive governments have led to feelings of depravation amongst the people.

“This provincial assembly asks the provincial government to recommend to the federal government to amend the Constitution of Pakistan to make Hazara a separate province,” the resolution reads.

Meanwhile, pro-Hazara province activists have called for a protest and sit-in in Islamabad on May 14, against the ignoring of their demands. Members of the Suba Hazara Tehrik criticised the PPP for ignoring the demand of Hazarawals at a meeting in Abbottabad on Friday, saying their demand is an administrative one in nature.

The road to Seraiki province

Pakistan Seraiki Party’s President Barrister Taj Muhammad Langah believes that creation of a Seraiki province is imperative, and a boundary commission should therefore be established immediately.

If the process is delayed, however, he has several short-term proposals to offer.

The Punjab Assembly could be divided informally into Punjab and Seraiki region, he said, while talking to The Express Tribune.

Members from the Seraiki regions in the Punjab Assembly should prepare budget proposals for their areas separately and allocation of funds to the Siraiki area should be based on population and the area’s contribution to the national economy, he said.

Similarly, the federation should have separate financial allocation in the budget, as well as in the NFC award, for a future Seraiki province, he added.

He proposed that until a separate province is created, the Punjab Assembly should, on temporary basis, be divided into two houses for legislation and development allocation purposes.

Published in The Express Tribune, May 5th, 2012.

Ethnicity and provincialism in Pakistan: What we don't normally hear or read

Author's note: I am of Baloch, Sindhi, Muhajir and Punjabi descent. Critics of my post are free to have their opinions, but the idea of Punjabi hegemony on my part can be ruled out due to my multiple ethnicities.

Over recent years, the cases of ethnic, tribal and provincial nationalism in Pakistan seemed to have reached a high peak.

Members within my own family are leaders of major provincial-nationalist organizations that seek greater rights for their province Sindh inside the state of Pakistan.

I myself was and still am a strong supporter of provincial equality within Pakistan. But that support has changed and my trust in many provincialist rights organizations has severely declined.

Over many years, provincial rights organizations have complained about being labeled "Indian agents." Much of their political messages and websites in Pakistan have been blocked/censored by the government and they have protested this as a violation of their freedom of expression.

But while complaining about such an accusation being given to them, I feel these provincial nationalists have done everything to earn this label, instead of fighting for a true and just cause. Let's first cover some examples of this.

During my summer holidays in Karachi back in 2005, I was sent an email by one of my parents who is a member of a Sindhi human rights organization. The email contained a speech by an Indian who attended this organization's seminar in Washington DC.

It started out with "as we all know, the state of Pakistan was carved out of Indian territory."

I didn't bother reading the rest of the email, knowing the bias it contained. It got me wondering, if this is a Sindhi cause, why does it have to involve the Indians? A few days later I another email containing an article about why Pakistan was "created."

Apparently according to this article, a group of Muslims in the British Raj could not stand the power of "Indian democracy" and so these corrupt Muslims elites opted for a separate state where they could rule over the masses like Kings and Queens.

As already explained in this article, the region of Pakistan was never a part of India, except under the Mauryan Empire which lasted about a century. Secondly, where was this so-called "Indian democracy" during the British Raj? At that time the subcontinent was under British imperial rule, so how can these supposed Muslims elites evade or fear a democracy that does not even exist?

Such claims are not just opposing points of view against the state of Pakistan, but outright lies. The worst part is that this is all being promoted by an organization which claims itself to be a defender of Sindhi rights, yet welcomes Indian propaganda itself.

It is now up to readers to decide weather the government and people of Pakistan have the right to be suspicious of such organizations or to accuse them of being "Indian agents."

It does not end with Indian support. This Sindhi organization that one of my parents helps runs claims to seek a greater audience amongst the people of Pakistan. Yet of all the interns that they recruit, I have not heard even of one hailing from any part of Pakistan.

In fact, these interns are from completely far ends of the world such as Sweden, America etc.

Then comes their alliance with Baloch organizations which seem to be so strongly pro-Afghan and pro-Indian. They also have interesting tactics of labeling any pro-Pakistani Balochis and Sindhis as "puppets of the Pakistani government" or pretending the so-called province of "Balochistan" is all Baloch ethnically speaking.

With these Baloch and Sindhi organizations working together, there is a pattern of sponsoring Indian & Afghan propaganda, blaming the ISI for everything that goes wrong in India and Afghanistan, labeling any pro-Pakistani Sindhi or Baloch a "government agent."

Interestingly they have a Kashmiri who is strangely pro-Indian and claims his people to be of Jewish origins (I do plan on discussing falsified Semitic ancestries in Pakistani populations in my other blog called History of Pakistan).

The establishment of the Durand line has also been condemned by these pro-Indian/Afghan separatists, which has been refuted in this article.

With all these things mentioned, there was even another Sindhi organization which decided not to partner with my parent and friends out of resentment for promoting Indian hegemonic agendas. This Sindhi organization supposedly departed to Pakistan in hopes of promoting provincial rights without involving pro-Indian/Afghan elements.(These people were in North America).

The organization(s) one of my parents works for even has close ties to Uighur separatists from China.

Interestingly enough, all these campaigners for provincial equality in Pakistan never work with separatists from India or Afghanistan. How far can they go convincing Pakistan and the world that they are not working on behalf of Indians and Afghans?

I'm not trying to imply that these people are indeed Indian RAW agents, though the RAW may have an indirect hand in funding and other means, but the nature of their activities is enough for them to decide how they'll be judged.

Besides that, their pro-Indian/Afghan policies are outright hypocrisy and immoral.

India and Afghanistan have treated their minorities even worse than Pakistan, so for these provincial nationalists to speak so highly of either countries indirectly advocates and tries to justify the inhumane treatment of Indian & Afghan minorities.

Of the organizations my parent (I won't mention which as I keep personal information private on the Internet) has worked for and the people they consist of, I have made two observations in provincial nationalists. This mainly applies to those from Sindh and Balochistan.

I cannot comment on other provinces as I have little knowledge of their provincial nationalists. The pro-Indian Kashmiri guy is an extremely rare case amongst his people.

Some negative things I've observed in Pakistani provincial nationalism:

Though I do not doubt that there are plenty of provincialists in Pakistan who are actually in search of human rights and greater autonomy and not acting as Indian/Afghan puppets (ie. the Sindhi group that I mentioned above which left for Pakistan), I've uncovered many things about the darker and more sinister side of Baloch and Sindhi nationalism.

Many Balochis and their political groups I've come across practice what I call Baloch fascism.

This practice is based on jingoistic, bigotry ideas and falsified beliefs that I have found through simple observance.

As examples, I've conversed with a Baloch separatist closely associated with my parent. He along with this mysterious Kashmiri play the game of blaming the ISI for everything that goes wrong in Pakistan, Afghanistan and India without any proof or evidence.

As I wrote before, it is hypocrisy for Pakistani provincialists to be defending India and Afghanistan since both countries have a worse history of treating their ethnic and religious minorities.

Some Sindhi and Baloch nationalists have defended this idea claiming they need this support.

But then this generates more hypocrisy on their part. When the Pakistani government aided religious and ethnic minorities in India and Afghanistan, these same Sindhi and Baloch nationalists have accused the Pakistani government of "meddling" in the affairs of the two countries.

Seminars and cultural events that have taken place hoist the Baloch Liberation Army flag; a flag which represents a single Baloch organization and not the people of Balochistan who have not even given their consent for this flag to represent them.

This Baloch separatist also seemed to be very enthusiastic on telling me he and his wife don't teach their children Urdu, the national language of Pakistan (which is fine by me).

But then the hypocrisy in all this is that the Baloch themselves have been imposing their language onto other ethnic groups of the province called "Balochistan" such as the Brahuis.

I have also been asked by this separatist on the legitimacy of the state of Pakistan. I was questioned weather Pakistan is a nation state to justify it's existence.

The definition of a nation state in the past might have meant one race, one culture one language.

However, today it mostly refers to a state binded by a people speaking a single language. Pakistan of course, does not fit this definition. But then the question is does the province of Balochistan?

Baloch fascism covers up many facts that I will discuss below, while highlighting only facts that suits it's cause. Baloch fascism is also mirrored by what I refer to as Sindhi Chauvinism.

Sindhi Chauvinism circles around the ideas of Sindh being the center of human civilization, Sindhi language and culture being older than all the other cultures in the region or that Punjabis and "Muhajirs" are the cause of Sindh's problems and that Sindhis have absolutely no part in it.

Again, most of Sindhi chauvinism can easily be disproved through historical and scientific facts.

Facts that Baloch fascists and Sindhi chauvinists never discuss:

The so-called land of "Balochistan" has never been home only to the Baloch people. On the subject of naming the land after an ethnic group, a fact to note is that the Iranian government refers to their Baloch province as "Sistan."

The Baloch seemed to have arrived much after other ethnic groups in "Balochistan" according tothis article. Also according to the article, the Baloch displaced other ethnic groups in the land that they arrived in.

I've also personally heard of claims that Balochi extremists have been oppressing Brahuis and pressuring them into assimilation.

The linked article and claims seem to be supported with two points:

1) A Brahui once told me that many Baloch tribal leaders have been pressuring his people to declare themselves as Baloch; in other words asking them to surrender and trade their Brahui identity for Baloch identity.

2) The theories of Baloch people arriving in the region from a more western direction coincides with the fact that Balochi is a Northwestern Iranic language, placing it closer to Kurdish, a language spoken in the northwestern areas of the Middle East.

Like all other language families and their subfamilies, the Iranic languages and dialects are broken into various categories based on geography. Languages having closer spoken proximity to other languages in other geographic locations and it's origin points are termed as such.

In this case, the modern Baloch language is closer to the Iranic languages spoken in Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran than it is to eastern Iranic languages such as Pashto.

With all that being mentioned, "Balochistan" is not and was not a land consisting simply of Balochis. These are key points that Baloch fascists will not discuss.

What Baloch fascists will also not discuss is that it is not Urdu that threatens the various languages of "Balochistan" but the Baloch language itself.

Urdu is still mostly spoken mostly in urbanized areas of Pakistan such as the main cities of the country and main towns of the provinces. In rural parts of Sindh, Balochistan, Kashmir, Pakhtunkhwa and perhaps even Punjab, Urdu is not used in daily life.

Even my own visits to Hyderabad showed me my relatives speaking to one another in Sindhi and hardly using any Urdu let alone English.

It is not the Punjabis nor the "Muhajirs" who have told Brahuis and other minorities in Southwestern Pakistan to trade their language and culture for Punjabi or Urdu, but rather certain Baloch supremacists who have fought vicious battles against them in the past.

Knowing the tense history between the Baloch and non-Baloch populations of the region; especially Brahuis, it is unlikely the Brahuis will submit to a separate state under Baloch domination.

The right to the territory of so-called Balochistan lies with various ethnic groups who have traditionally inhabited it, not simply just the Baloch. The Gwader port was acquired by Pakistan from Oman around 1958, which puts Baloch-centric claims on a significant portion of the coast of that province into question.

Another fact that Baloch fascists and their masters in Afghanistan and India will not mention is that Balochis constitute only around two to three percent of Pakistan's population at the most. Within that two percent, only a small handful consist of separatists.

This means there are plenty of Balochis (including close friends of mine) loyal to their country Pakistan. In fact even a friend of mine of Iranian-Baloch origin works for the ISI.

With a small handful of Baloch fascists using backing from Afghanistan and India, there is little chance of Balochistan separating from Pakistan; knowing the enormous size of the Pakistani armed forces added with their superior weapons technology to the separatist militants.

Below are thought provoking videos to those who have been sympathetic to Baloch separatism. The first reaction by many Baloch and Sindhi separatists might be that these Balochis are government puppets. But then again, these pro-Pakistan Balochis can easily point back the finger at the separatists and accuse them of being Indian/Afghan pawns:

As mentioned before, Sindhi chauvinism revolves around crazy ideas of Sindh being the cradle of civilization and Sindhi predating other languages of Pakistan. It also speaks of the victimization of Sindhi people at the hands of the evil Punjabis and their "Muhajir" puppets.

I even got an email by a Sindhi chauvinist who discussed Sindh's history periodically.

The end of his email concluded that the Sindhi language has evolved over a period of five thousand years.

Let's discuss Sindhi chauvinism starting with this rather far-fetched claim. As most educated people know, Sindhi is an Indo-Aryan language, part of the Indo-European family of languages.

According to most historians and linguists, there is no evidence of Indo-European (IE) languages having a presence in the Indus Valley region as far back as five thousand years.

In fact, five thousand years ago, linguists estimate that most of the IE languages were still mostly intact meaning they were the same language before breaking off into various languages due to geographic separation between their speakers.

Also according to linguistic, historic and archeological evidence, the IE languages arrived in the Indus Valley/Pakistan around two thousand to three thousand BC, ruling out the belief that Sindhi was spoken in Sindh as far back as five thousand years.

Sindhi, like all the Indo-Iranic languages of Pakistan were brought to the country through migration.

Opponents of these theories can easily research the facts for themselves. No symbol or artifact of the Indus Valley Civilization connects to the artifacts or symbols of ancient Indo-Europeans. To better understand this, please see my History of Pakistan blog and search books on this subject such as Indo-European culture or Proto-Indo-European Language and Culture by Benjamin Fortson.

Even genetic evidence contradicts Sindhi chauvinistic beliefs of Sindhis being the exact same people of the Indus Civilization.

Sindhi chauvinists also like to spread the idea of Sindhi victimization of their people without taking the slightest bit of responsibility for it.

In 1947 Karachi and other parts of Sindh were flooded with Muslim immigrants from all over the subcontinent. The Sindhis welcomed and sheltered them. They hardly reacted nor showed concerns to the massive numbers of the immigrants.

When I was once at a Sindhi gathering at a restaurant in UAE with my parent, I heard the same cries of complaint from leaders that the Punjabis have taken over Sindh and given it to the Muhajirs.

I have heard these cries countless times before. But another Sindhi in the meeting pointed out that Sindhis did not raise any voice or opposition to Muhajir and Punjabi domination of their province; nor did they stand up to their oppressors.

Instead they welcomed them during the over flood of the Muhajirs into Sindh. Even with the rise of the MQM in the 1980s till today, there was hardly any strong reaction or resistance from the Sindhi community.

I myself have thought this for so long. Not only that, but Sindhis I've spoken to insist that Muhajir aggression must be countered with peace and love.

Is it even a wonder why Muhajirs have managed to dominate Sindhis in their own province despite being outnumbered by them?

Sindhi provincial chauvinists also don't mention the fact that Sindh also has smaller minorities such as Siriakis and Tharis.

Sure Sindhis can argue, they are not that different from themselves. But then neither are Punjabis that different. Linguistically speaking Sindhi and Punjabi are both Northwestern Indo-Aryan languages. The two peoples are almost like first cousins both having similar language, culture and traditions.

My own maternal grandmother's father was Northern Punjabi despite the fact that she was born, raised in Sindh and spoke Sindhi. Punjabi and Sindhi are both derived from the same Northwestern Sanskrit dialect.

My thoughts and opinions on provincial nationalism in Pakistan:

Firstly, if provincial rights are going to be made critical issues in Pakistani politics, the provincial nationalists themselves have to reform and be objective if they are ever to achieve their goals.

For this to happen they need a large audience amongst not just politicians but the people of Pakistan who are sympathetic to their cause.

And to achieve that they must stop working with the Indian and Afghan governments to reduce suspicion upon themselves.

Particularly Sindhis and Balochis need to also keep the fascists and chauvinists out of their organizations and also open doors to interns from all over Pakistan to work with them instead of bringing in people who have little knowledge on Pakistani history and politics.

Sindhis and Balochis also have to stop spreading biased ideas that their fascist and chauvinistic members mislead their communities into believing. Discrimination needs to come to an end- including Baloch discrimination towards Brahuis and other non-Balochis in so-called "Balochistan."

This doesn't mean I defend the armies brutal atrocities in Sindh and especially Balochistan. Nor do I advocate taking energy from Balochistan to support Punjab's needs without any benefit.

Also with the coming of solar technology and temperatures soaring in Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan the government and peoples should invest more in solar technology so more and more people have equal access to energy.

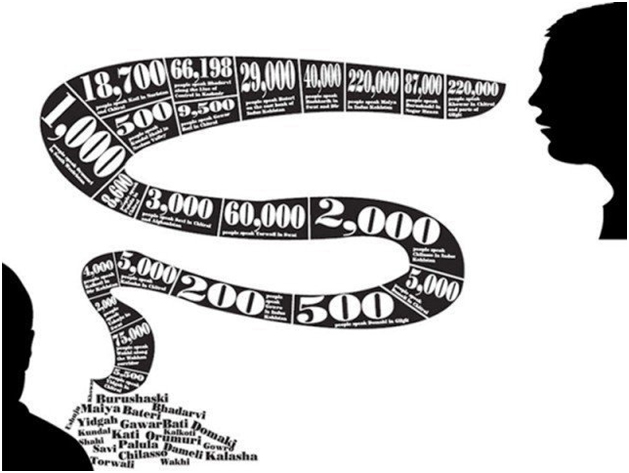

Provincial autonomy and equality is the solution to unity in Pakistan combined with Pan-Indo-Iranism. The education system must have the languages of the ethnic minorities available throughout Pakistan. Punjabi children should be allowed to study Punjabi at school as should every ethnic group in Pakistan alongside the federal language Urdu.

Brahui children should be allowed to study their own language and study Baloch and Urdu as additional options.

People who speak Urdu as a first language must then learn the main language of their province.

Overall there is also thought about the people of Pakistan as a whole. Pakistani people have much of a shared identity based on linguistic, genetic and cultural lines. Most Pakistanis descend from ancient Indo-Iranic tribes that spanned across Eurasia before settling into the Indus Valley and merging with the native population(s).

This idea can be used to forge a national Indo-Iranic identity, for most multi-lingual and multi-ethnic countries do not have common language family, unlike Pakistan.

For all this to happen, unbiased knowledge of the history and politics of Pakistan must be spread and promoted.

Only then I feel, will the issue of ethnicity and provincialism in Pakistan will finally be resolved and satisfied.

Curtsey: http://pakindependent.blogspot.com/

Ethnicity and Regional Aspirations In Pakistan

31 December 2001

By Sudhir k. Singh

Ethnicity is not a new phenomenon in world politics. For a long time ethnicity was regarded as the sole domain of sociologists, where as on studies on International Relations and intra-regional developments it received little attention.

After the nation building efforts of Bismarck and Garibaldi succeeded in Europe during the 19th century, the European States were mainly considered mono-national states, where the influence of any sub-national ethnic groups was largely neglected. After the end of the Second World War, with numerous multinational multiethnic colonised nations becoming independent, the issue of ethnicity assumed enormous scholarly significance. Many of the post-colonial states have faced the problem of ethnicity in one form or the other ever since. In many cases, ethnic assertion has assumed violent forms. Since the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the reassertion of the ethnic movements, especially in violent forms, across the globe has forced many states to look at it more closely. As Horbwitz says, ethnicity has fought and fled and burned its way into public and scholarly consciousness.

Before coming to the ethnic problems in pakistan, it will be helpful to define ethnicity. Etymologically speaking the word 'ethnic' is derived from the Greek word 'ethnikos'; which referred to (a) non-Christian 'pagans' (b) major population groups sharing common cultural and racial traits; primitive cultures. Ethnicity denotes the group behaviour of members seeking a common ancestry with inherent individual variations. It is also a reflection of one's own perception of one self as the member of the particular group. According to the Prof. Dawa Norbu, "an ethnic group is discrete social organization within which mass mobilization and social communication may be affected. And ethnicity provided the potent raw material for nationalism that makes sense only to the members of that ethnic group. its primary function is to differentiate the group members from the generalised others".

Out of 132 countries in 1992, there were only a dozen which could be considered homogeneous; 25 had a single ethnic group accounting for 90% of the total population while another 25 countries had an ethnic majority of 75%. 31 countries had a single ethnic group accounting for 50 to 75 % of the total population whereas in 39 countries no single group exceeded half of the total population. In a few European and Latin American cases, one single cases, one single ethnic group would account for 75 % of the total population.

The Pakistan Case

The country under study here - Pakistan - comes under the third level, with one dominant ethnic group accounting for 50 to 75 % of the population, as the Punjabis are around 56 % of the total population. In the case of Pakistan, the regional assertion based on the ethnic identities came to the fore in more pronounced ways in the 1990s. Ethnic disaffection was simmering in Baluchistan and NWFP since the 1970s. Similarly, the Mohajirs of Pakistan were emerging as an important ethnic group with the growth of MQM since the 1980s as a major force in Urban centers in Sindh, especially in Karachi and the twin city of Hyderabad. the Sindhi assertion has along been there since 1950s. All this has to be studied against the background of the separatism within Pakistan that climaxed in the formation of Bangladesh in 1971.

Historical Background

To examine the ethnicity in pakistan, we will have to search for its root in the Pakistan movement. It was a movement of a special nature. Led by the Muslim League under leadership of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the muslims of British India were fed with the fond hope of an Islamic State as opposed to the secular, democratic ideals of State Advocated by the Indian National Congress, which sought to unify diversities. While the Congress Party organised constructive programmes like, women welfare, eradication of illiteracy, untouchability, decentralisation of power and so on, the leaders of the Pakistan movement clung to the anti-Congress agenda and their strategy of exploitation of the religious sentiments which culminated in Direct Action Day in August 1946. The idea of 'Islamic State' overstepped all other secular concerns and after the foundation of the State of Pakistan on August 14, 1947, there was no further impetus to build a nation out of several disparate ethnic groups. The demand for an Islamic Pakistan was essentially a demand for political empowerment, and was therefore not so religious in intent. As such, 'Islam' did not act any more as a binding force once Pakistan came into existence. It is of little surprise that the most prominent of India's Ulema and religious leaders, notably those in the Jamaat-i-Ulama-i-Hind (party of Indian Ulema) did not look favourably upon Muslim Communalism and instead supported the Congress Party's notion of United India. After independence, the positive programmatic policies of the Congress Party were incorporated into the Indian Constitution as the guidelines of a welfare state. In contrast, the ideological foundation of Pakistan as a unified Muslim nation has not yet taken roots in the minds of the people in Pakistan. The failure of the process of drafting of a constitution for the state of Pakistan revealed the irreconcilable differences among various groups seeking to impose their World-view on the people of Pakistan. this lack of consensus has marked the nature of the Pakistani polity ever since.

Pakistan movement was very strong in Muslim minority provinces; where Muslims feared Hindu domination most. Pakistan, however, was created in the Muslim majority Provinces of northwestern India and Bengal. Ethnic, linguistic and cultural distinctions set them apart. The socio-cultural outlook of the Muslim populations of the Muslim minority provinces (Bihar, U.P, M.P, Hyderabad) had very little similarity with the Muslims in Sindh, Baluchistan, NWFP and even in Punjab. The Sindhis, Punjabis, Bengalis, Biharis, or Hyderabadis followed different customs. they were different people who had more in common with their Hindu neighbours than with muslims of other provinces. The founding fathers of Pakistan had hoped, however, that the cementing force of Islam would maintain the integrity and unity of the country despite the presence of various ethnic groups.

After the passing away both Jinnah and Liaquat, the League virtually became leaderless. The League leadership was heavily Mohajir dominated. Just after independence, out of 27 top posts of the country including P.M, C.M, Governor, Attorney General etc., Mohajirs numbered about 18. They were very well-educated in comparison to the other ethnic groups. However, the oligarchic League leadership delayed the formation of the constitution, and remained over-dependent upon the old colonial set-up, which again had its ethnic bias with Mohajirs and Punjabis having an upper hand.