|

Revolution to ruins:The tragic fall of Bradlaugh Hall

AOWN ALI

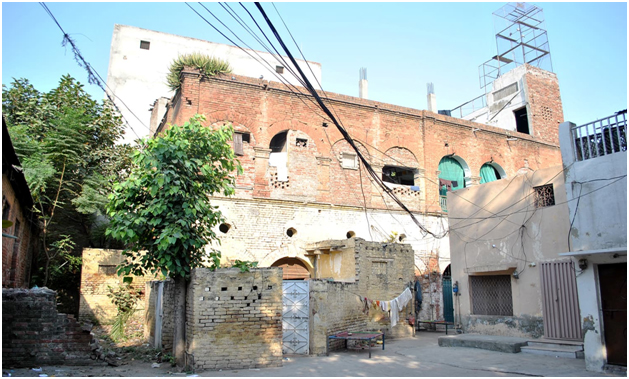

The Bradlaugh Hall, a hallmark of the anti-colonial freedom movement in the subcontinent, is crumbling behind the district courts of Lahore. For almost half a century, the famous hall has served as the exclusive venue of notable political events in Lahore, but the historic building itself has been left to fend for itself against hazards, natural and man-made.

Built in the late 19th century on Rattigan Road Lahore, the Bradlaugh Hall would play host to almost all the notable leadership of India, particularly for political figures in Punjab.

Irrespective of clan, creed or even political ideologies, the hall was a famous rendezvous for Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs alike; they would organise political sessions, give receptions to visiting leaders, and hold literary sittings or mushairas (poetry recitings).

We find that Allama Muhammad Iqbal, Maulana Zafar Ali Khan, Dr Muhammad Ashraf, Mian Ifthikhar uddin and Malik Barkat Ali are among the stalwarts of freedom who frequently visited and gave speeches at the Bradlaugh Hall.

Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah also delivered at least one speech here, on May 24, 1924, in a Khilafat Movement session.

Bradlaugh Hall on Rattigan Road in Lahore.

It was constructed in loving memory of Charles Bradlaugh, a British member of parliament and a great supporter of the Indian freedom movement.

The upper plaque is inscribed with a Quranic verse. The lower one reads 'National Technical Institute' (The hall was used for technical education after the partition).

The building seems to have been designed with British architectural elements but with local climate and requirements in view.

The front facade of the building.

It once used to host everything from theatre shows to political gatherings.

The Bradlaugh Hall was constructed by funds collected from the annual session of Indian National Congress held in Lahore in 1893, and was attributed to Mr Charles Bradlaugh, a British MP, who, for his utmost support of Indian self-rule, was greatly admired in Indian circles.

Actually, it was Sardar Dyal Singh who realised the need for a suitable public place to hold political events in Lahore. At that time, there were only two halls in Lahore, the Town Hall of municipal office and Montgomery Hall in Lawrence Garden (Jinnah Garden). Both were owned by the government and not available for political events.

So the Indian Association, the earliest political organisation in Lahore, used to hold its meetings in the courtyard of The Tribune, a weekly newspaper run by Sardar Dyal Singh. He was a member and patron of the Indian association. No wonder he felt the need for a dedicated site for political purposes.

Singh was also very keen to have a session of the Indian National Congress held in Lahore. In 1888, at the Allahabad session, Punjab’s invitation was accepted and Congress agreed to meet in Lahore in December 1893.

Dyal Singh was elected chairman of the reception committee of the session, which was a great success. All the tickets sold out and after meeting all expenses, the Congress saved Rs10,000, which became the nucleus fund to construct the Bradlaugh Hall in Lahore.

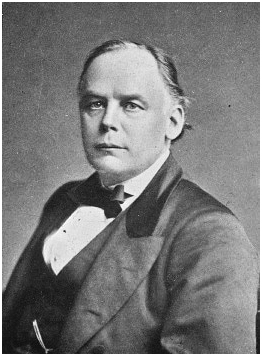

Charles Bradlaugh — the "Member for India"

Charles Bradlaugh was one of the notable liberals and freethinkers of Victorian England, and an early advocate for women's right to vote (a 'radical' stance at that time), birth control, republicanism, social reform and trade unionism. For his deep interest in the Indian freedom movement, Mr Bradlaugh was invited to the 5th annual session of the Congress, held in Bombay in December 1889.

Bradlaugh’s daughter Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner wrote his biography Charles Bradlaugh: A Record of His Life and Work:

“In India, he was joyfully called the "Member for India," and at home, his views on Indian matters were heard with growing respect. He took up the cause of India with no thought or prospect of personal gain; out of sheer zeal for justice and hatred of oppression.”

Charles Bradlaugh. —Wiki Commons

Regarding the said visit of India in 1889, Bradlaugh’s biographer further notes, “Nothing could be more judicious and restrained than his brief address to the Congress on his brief visit to India after his dangerous illness of 1889.”

Bradlaugh’s speech concluded with following words:

“If I do rightly, you will be generous within your judgment; and that even if I do not always plead with the voice that you would speak with, you will believe that I have done my best. And that I meant my best to be the greater happiness for India's people, greater peace for Britain's rule, greater comfort for the whole of Britain's subjects.”

Annie Besant was a socialist, theosophist and a longtime colleague and partner of Mr Bradlaugh. For her theosophical work, she had travelled to India in the late 19th century, and went on to be elected as president of the Indian National Congress in 1917. Besant relates that the whole speech was punctuated with cheers.

“The speech concluded to tumultuous applause, his first speech in India, and alas his last,” she writes.

Thus, the Bradlaugh Hall, founded under the auspices of Congress, had become an epicentre of political gatherings in Lahore since its inauguration. In its early years, it helped facilitate the labour and peasants’ movement, especially the influential movement of the peasants (known as “Pagri Sambhal Jatta”) of Lyallpur (Faisalabad), in 1905.

National College — where Bhagat Singh turned revolutionary

Later, in 1915, the “Ghadar Party” also had its base in Bradlaugh Hall, Lahore. By the 1920s, it had become well-known across India as a prominent political hub.

That was the time when Lala Lajpat Rai founded the National College here. After the non-cooperation call of Mr Gandhi, the students of Lahore collected funds for setting up this college.

Bhagat Singh had also left his DAV School (now Government Muslim High School No. 2) and joined the National College. Here, he spent almost four years as a student (1922-26), an instrumental period which prepared him for the acts that would eventually make him a national hero.

At the National College, Bhagat Singh found revolutionary companions like Sukhdev, Yesh Pal, Ram Krishna and Bhagwati Charan Vohra. Here, these young patriots formed the “Naujawan Bharat Sabha” in March 1926. The objective was clear: to channelise the nationalist movement on ideological (resistant) lines.

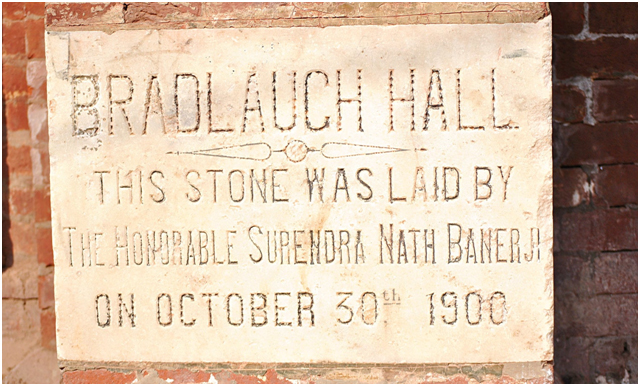

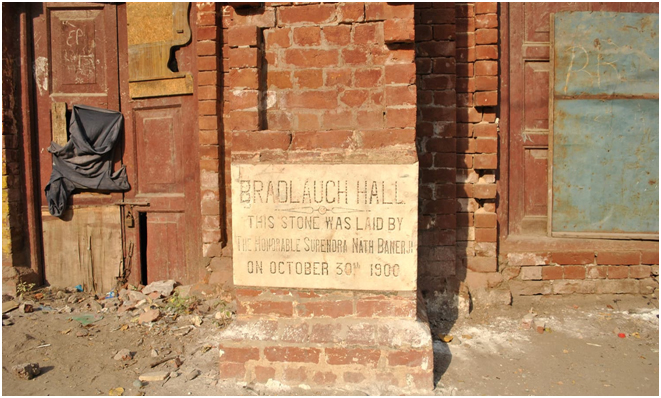

Surendar Nath Banerji – one of the earliest Indian political leaders during the British Raj and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress – laid the plaque on October 30, 1900, at the inauguration of the Hall.

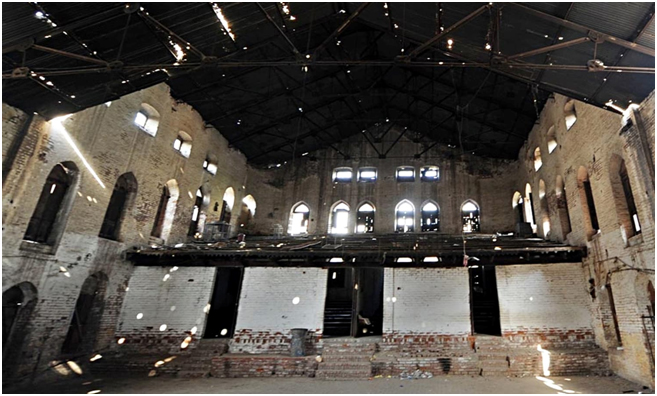

Bradlaugh Hall consists of numerous rooms, a pavilion and a vast area for public gatherings.

The entire building is covered with a metal roofing, like at railway stations.

The historic site is now wasting away in neglect.

Soon after the establishment of Sabha, its members observed the death anniversary of Kartar Singh Sarabha, a young revolutionary and leading luminary of the Ghadar Party who was executed in November 1915 for his role in the Ghadar Conspiracy Case (Lahore conspiracy case of 1914-15).

A portrait of Kartar Singh, covered with a white cloth, was kept in the Bradlaugh Hall. Durgawati Devi (wife of Bhagwati Charan) and Sushila Devi paid homage to the martyr by sprinkling blood from their fingers on to the white cloth.

Sabha did a great deal of work in politicising the middle class youth, students and peasantry. The revolutionary ideas of freedom, equality and economic emancipation stirred them to no end. By the end of 1929, the organisational units of Sabha had established in all major districts of Punjab, as well as in Sindh, UP and even in far-off cities like Bombay.

All these years, the Bradlaugh Hall in Lahore had been the headquarters of Naujawan Bharat Sabha. After the arrest of its founder member, Bhagat Singh, and several others in April 1929, political activities gained more momentum at the Bradlaugh Hall.

But on 7 October 1930, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were sentenced to death. As the Naujawan Bharat Sabha was declared illegal in June 1930, it was revived under the cover of “Bhagat Singh Appeal Committees”.

The legal defense for Bhagat was carried out at Sabha’s office in Bradlaugh Hall, as was Sardar Kishan Singh's appeal for his son, Bhagat. But the appeals were rejected, and on 23 March 1931, three young freedom fighters in their early 20s ended up sacrificing their precious lives.

A few leaders of the Sabha then planned to establish memorials for the three. On 28 April 1931, they met at the Bradlaugh Hall and formed a committee named “All India Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev Memorial Committee”, but it could do nothing. Naujawan Bharat Sabha could no longer survive after 1931. Its strength and activities decreased and organisational network disrupted after the death of Bhagat and his companions.

That was also the end of a vibrant decade of the Bradlaugh Hall.

In 1956, the building was was allotted to some engineers who founded the 'Milli Techniki Idara' here.

Under the Milli Techniki Idara (National Technical Institute), land grabbing and illegal encroachments were rampant.

In the late '90s, the Milli Techniki Idara or National Technical Institute (which was allotted the building in 1956) ceased its educational activities and rented the building further to various tenants.

The teachers of nearby government high schools, who had taken possession of this historic property from the Milli Techniki Idara, used it as tuition centres (image taken in March 2008).

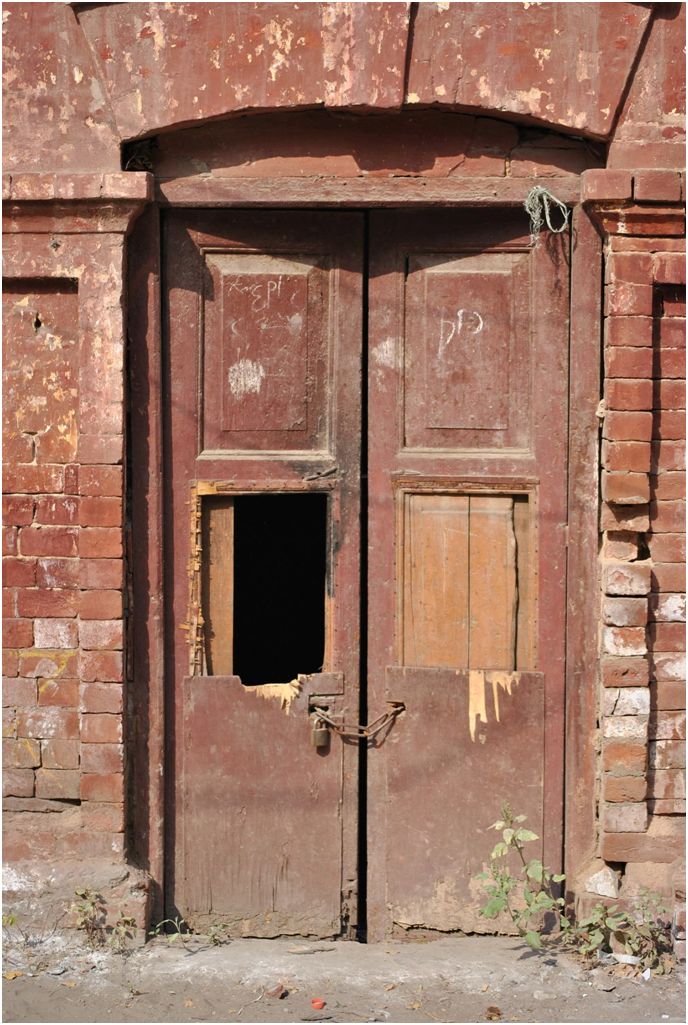

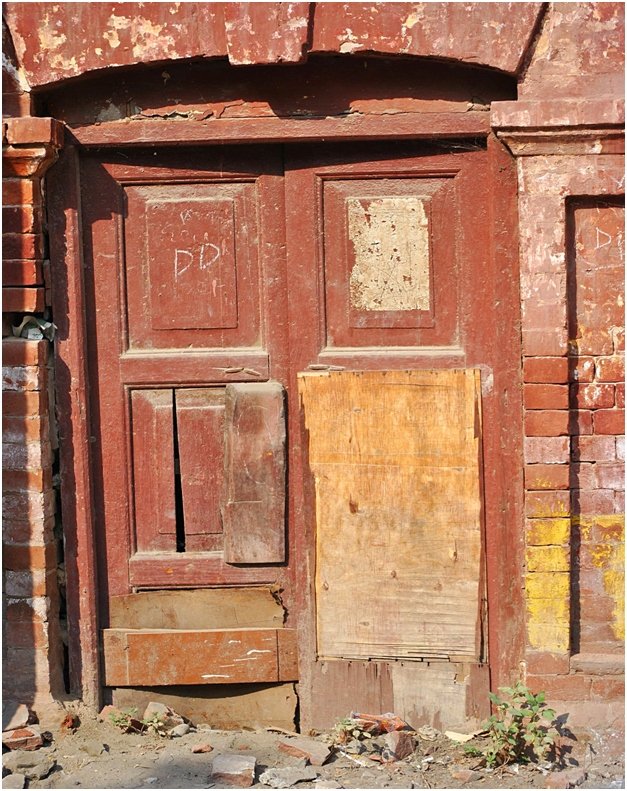

But now the Evacuee Trust Property Board has taken over the building and all the entry points are sealed.

Whereas previously, it was encroached upon, the hall is now wasting away in neglect.

Instead of keeping the buildings protected, the Evacuee Trust Board goes for the easier option of keeping it locked.

A forum for arts and literature

Apart from its political role, the Bradlaugh Hall was also a forum for activities related to literature, art and culture. Stage dramas, theatrical performances and mushairas were a common occurrence.

The Parsi Theatrical Companies of Cowasjee and Habib Seth were very popular, and both used to perform at the Bradlaugh Hall. In 1903, Narayan Prasad Betab’s drama Kasauti was played here.

In Abb Woh Lahore Kahan, F.E. Chaudhrya – the celebrated press photographer of Lahore – has discussed many such events in good detail. The book is based on his exclusive interviews with veteran journalist Muneer Ahmad Muneer.

In the preface, Muneer also touches upon the cultural aspects of Lahore and reminds us of the role of Bradlaugh in such activities, particularly the cherished details of the visit of the legendary singer and dancer Gauhar Jaan Kalkattewali, in 1912.

All the tickets sold out rapidly. The performance was held at the Bradlaugh Hall and all the Muslim, Hindu and Sikh upper class; including Nawab Muhammad Ali Khan Qazalbash, Sir Umar Hayat Khan Tiwana, Sir Dia Kishan Kaul, Raja Narider Nath, Faqir Iftkhar uddin and Mian Saraj uddin, were among the audience of that concert.

F.E. Chaudhry also shares the details of a mushaira that was declared the largest mushaira of India. It was organised by the government in 1919 at Bradlaugh Hall as a World War-I victory ceremony. Here, Allama Iqbal recited his poem شعاع آفتاب (Shoa'a-e-Aftab or 'A sun ray').

Ramlila, the dramatic folk enactment of Rama and Ravan was another performing art show which was held every year for over 10 or more consecutive nights at Bradlaugh Hall.

In his book Lahore: A Sentimental Journey, Pran Nevile, an acclaimed author of Indian art, culture and history, says:

“As I was recalling my student days, I was reminded of the famous Bradlaugh Hall, where we used to gather for all kinds of meetings, especially those of a political nature connected with the national freedom movement. I still remember student leaders like Rajbans Krishan, Promod Chandra, Yash Pal, I.K. Gujral and Mazhar Ali addressing the student crowd at Bradlaugh Hall.”

But Nevile was probably talking about the early '40s. In the later years, things began changing rapidly, and the political scenario of the Indian subcontinent too. In the 1946 elections, Muslim League won the majority in Punjab, which marked the end of Congress in this province. Although the League was prevented from forming a coalition government by the Congress and the Unionists, the anti-League coalition collapsed soon.

As an active hub of political activities, Bradlaugh Hall was about to complete half a century. Actually, it had almost become the political epicentre in Lahore.

The handover to 'Milli Techniki Idara' and subsequent neglect

For a decade after independence, Bradlaugh Hall was used for various services; providing shelter to the migrants from Amritsar, as a warehouse for iron merchants and as a grain silo for the food department.

In 1956, Bradlaugh Hall and its adjoining area were flooded with heavy storm water. As the building became useless for food storage, the hall was allotted to “Milli Techniki Idara” (National Technical Institute). This institute of technical education was formed in 1953 by engineering graduates from Aligarh University.

Rafiq Chishti, a trustee of Milli Techniqui Idara, told me the story of this allotment some years ago.

In 1956, Muhammad Kibria, the head of “Milli Techniqui Idara” submitted an application to justice (r) Jamil Hussain Rizvi, the Minister for Law and Rehabilitation, for the allotment of a building. On his approval, secretary Evacuee Trust Property Board allotted Bradlaugh Hall to Kibria for 99 years. It was handed over to the Idara in 1957.

However, in the late '90s, Milli Techniqui Idara ceased its educational activities and the management rented the building to various persons, including the teachers of nearby government schools. Although Bradlaugh Hall housed the Milli Techniki Idara for about four decades, this was also the worst period for this historic building, as it was in this period that all the land grabbings and illegal interventions took place. And the trustees of the Idara can’t negate the fact that the area was being exploited all for personal and monetary interests.

The terrible conditions and signs of deliberate damage all around the hall.

The terrible conditions and signs of deliberate damage all around the hall.

All the windowpanes and doors are cracked and the iron roof is crumbling.

The wrecked state of the podium where the political leadership of the Indian subcontinent used to give out addresses. Below the pavilion, the gallery seats had been modified into rooms through partitions constructed by school teachers.

Another view of the hall interior.

(The above images are from March 2008. Now, the conditions are far worse.)

It was not possible to find an authentic source who covers the details of Bradlaugh Hall, especially ones regarding the designing and construction of this superb piece of architecture. Obviously, the building can be described as an architectural fantasy, and whoever designed it was, of course a trained architect, certainly impressed by British architecture, but fairly well-informed of local requirements and climate too.

The building bears the impression of architectural and ideological characteristics of Leicester Secular Hall, built in 1881 by the Leicester secular society, England. It may be pertinent to mention that Leicester Hall was proposed in 1872 after George Jacob Holyoake – a mentor of Bradlaugh and a secularist – was not allowed to use the public building for his lectures.

Bradlaugh Hall consists of numerous rooms, a pavilion and a vast area for public gatherings. The entire building is covered with an iron roof, like the railway stations. In the eastern side of the hall is a pavilion, which was used as stage and to reach staircases along both sides of the walls.

Since the Evacuee Trust Property Board took over the hall from Milli Techniki Idara a few years ago, all the entry points have been sealed. But I had managed to visit the hall and photograph it from the inside while the hall was still under the control of the tenants.

The interior was terrible damaged all around. The podium, where once, India's leading political figures used to give speeches from, was utterly wrecked. Below the pavilion, the gallery seats had been modified into rooms by constructing partitions. This destruction of property was caused by the teachers of nearby government high schools, who had taken possession of this historic property from Milli Techniki Idara, and used it for various purposes, including tuition centres.

On fantasised histories

Apart from the negligence, Bradlaugh Hall is also a victim of fake narratives and ignorance.

Historical events, personalities and places are routinely fantasised, and described more often than not under the influence of that fantasy. Something similar happened in the case of Bradlaugh Hall.

In dozens of web and newspaper articles and books (mostly in Urdu), authors have presumed that Mr Bradlaugh was awarded the contract for laying down railway tracks in western India, and that when the British government learned about his sympathy for the Indians, they cancelled his contract and ordered him to leave India.

Then, the clever Mr Bradlaugh took a boat and anchored in Ravi, indicating to the government that he was not on Indian land anymore. But the government forced him to leave the country. The story goes on to say that he had purchased some land in Lahore, where Bradlaugh Hall was constructed on his will.

However, none of the writers citing these stories actually bothered to find out who who Bradlaugh was in fact. His extensive biography, written by Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner, his daughter and ideological successor, should definitely be regarded as an authentic source in this regard.

The biography tells us that Mr Bradlaugh had visited India only in December 1889 and it was also a brief trip as he returned from Bombay at the end of January 1890, mainly due to health issues. Mr. Bradlaugh actually wished to visit India; partially it was also a reason behind his joining the service of East India Company in 1851. But he was destined for home service and stationed in Dublin, Ireland.

Bradlaugh had also never been a railway contractor, after three years of military service almost all his life passed in learning, lecturing and in political struggle. It was really a rigorous life and he died poor and in debt.

But in case of history such assumption and fantasies mean nothing except pushing us away from the facts. And the fact here is simple: a building, a witness of history is crumbling; now the question is what should be our line of action?

Bibliography Books:

• Charles Bradlaugh: A Record of His Life and Work by Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner

• Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia as seen by his contemporaries. Edited by Ihsan H. Nadiem

• How India Wrought For Freedom: The Story of The National Congress by Annie Besant

• Pan-Islam in British Indian Politics: A Study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918-1924by Naeem Qureshi

• Indian Muslims and Partition of India by S.M. Ikram

• Early Aryans to Swaraj (Vol 10, Modern India) by S.R. Bakshi, S.Gajrani, Hari Singh

• Abb Woh Lahore Kahan by Muneer Ahmad Muneer

• Lahore A Sentimental Journey by Pran Nevile

• Stages of Life: Indian Theatre Autobiographies by Kathryn Hansen

News articles and research papers:

• 'Punjab’s first freedom fighter: Remembering Dyal Singh, founder of The Tribune by Madan Gopal The Tribune, Chandigarh India

• 'Towards Independence and Socialist Republic: Naujawan Bharat Sabha' by Irfan Habib and S. K. Mittal. Social Scientist, vol 86, 87, Sept-Oct 1979

Aown Ali is a Lahore based photojournalist, particularly interested in documenting architecture worth historic significant.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM,September 26,2015

|