|

The Dynamics of Punjab’s economy

NASIR JAMAL

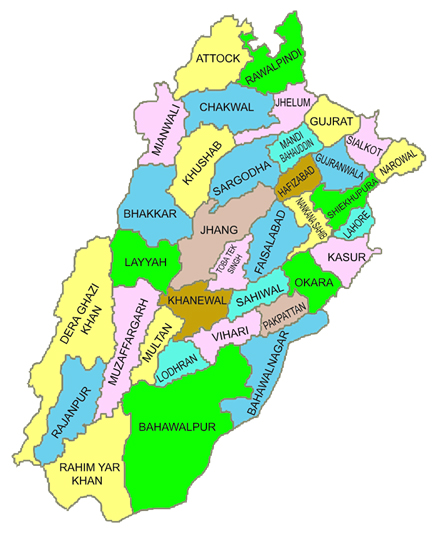

"Punjab Pakistan Districts" by Warraich Sahib - Own work.

OVER the years, Pakistan’s four federating units have successfully managed to evolve what officials call as a “Pakistani common market”, a feat that Europe is still striving to achieve even after decades of effort in this direction.

What is unique about Pakistan that has enabled it to achieve the common market? Officials give credit for this achievement to the economic freedoms enshrined in the country’s constitution, which allows free mobility of goods, services, capital and labour from one province to another.

At the same time, the officials say, the “geographical contiguity of the country’s four federating units and economic and social inter-linkages has played a critical role in their economic integration”.

All these factors have shaped up the existing economic structure of the country and helped it develop a common market, allowing various regions to develop their comparative advantages. The country’s existing economic structure that created the common market, has also reinforced a highly centralized tax system, which is often the cause of dispute and bickering amongst the four provinces when it comes to distribution of financial resources between them.

Moreover, it is hampering the four provinces’ ability to calculate their respective GDP, and base their future economic and development policies on it.

As a consequence, what we have at present is the national GDP. Of late, nevertheless, the provincial governments are fast realizing the need for calculating their respective, separate GDP for shaping up their future economic and development strategies.

Punjab appears to have taken the lead over the other provinces in this respect by preparing the Punjab Economic Report. The report has been brought out under the $500 million Punjab Resource Management Programme (PRMP). The ADB (Asian Development Bank) is financing the project that aims at restructuring the provincial finances.

Although the report itself admits that the effort to calculate the provincial GDP was hampered by the non-availability of reliable, recorded data on different sectors, yet the effort must be commended as the first step in the right direction. The report is the result of a combined effort of the provincial government, the World Bank, the Department for International Development (DFID) of the UK, and the ADB. The objective of the report is to provide an “analytical and policy underpinning for the Punjab’s development strategy”.

The provincial government’s strategy for economic development of the province stands on five pillars – improving governance, strengthening fiscal and financial structure, creating an enabling environment for private sector-led growth, reforming delivery of public services, and addressing the provincial economy’s vulnerability to shocks.

The Punjab Economic Report, according to its authors, offers a first cut at operationalizing the strategy. “It identifies what the Punjab government needs to do, primarily in a relatively short-term, and what actions it needs to start in order to be completed in the medium-term,” they write.

The document gives a fairly good idea about the historical background of the province’s financial condition as it attempts to calculate the provincial GDP growth rate during 1990-02. As is the case, the Punjab’s GDP (agriculture, services and industry) grew at an amazingly high rate of 9.2 per cent during 1991-92 as against the national average of 7.6 per cent. However, this growth rate dropped to 1.4 per cent the very next year as compared to national average of 2.1 per cent to surge again to 6.4 per cent against the national GDP growth rate of 5.1 per cent in 1994-95.

The report indicates that the Punjab had achieved GDP growth rate of five per cent or more only four times during the 12-year period under review. Twice, it registered growth of less than two per cent, and only once more than nine per cent.

During the remaining years, the provincial GDP rate kept fluctuating between four and five per cent. The Punjab’s services sector grew at an average rate of five per cent during the period under review, which compares to 4.5 per cent growth recorded by the industry and 3.6 per cent registered by the agriculture sector.

In short, the Punjab’s GDP growth rate stood at 4.5 per cent during the period under review. This compares with the national GDP growth rate average of 4.1 per cent. Only four times during the period under review, the national economy grew faster than the provincial. Twice both the central and provincial economies had grown at the same rate while the province recorded a higher growth rate during the remaining six years.

While the Punjab grew faster than the “rest of Pakistan” for at least six years during 1991-02, it trailed behind the aggregate GDP growth of the three smaller provinces. On an average the rest of Pakistan grew by 3.7 per cent during 12 years being reviewed as compared with the Punjab’s average growth rate of 4.5 per cent.

Another important aspect of the report is that it analyzes the characteristics of the income of the residents of the province and profiles labour force and market, admitting that poverty had not been reduced meaningfully due to the failure of the economy to grow sufficiently fast during the period. The incidence of poverty rose to 34.1 per cent – with 37 per cent rural and 27 per cent urban population living below the poverty line – in 2001-02 from 28.2 per cent – with 31.9 per cent rural and 26.5 per cent urban population living below the poverty line – in 1993-94.

The Punjab seems relatively better off than other provinces with a differential of 3.2 per cent when percentage of the poor living in the largest province is matched with the national average of 37.3 per cent. But in effect the province houses the highest number of poor people – around 26 million or more – in the country as it accounts for over 65 per cent of the country’s total population. One major factor responsible for the current incidence of poverty in the province is stated to be higher than the national unemployment rate. The provincial average of unemployment has been calculated at 8.5 per cent (in 2001-02), which compares with the national average of 7.8 per cent.

Vulnerability, defined as proximity to the poverty line, is also quite high with 75 per cent population of the province living on less than 150 per cent of the poverty line and 63 per cent on less than 125 per cent of the poverty line. Such people are vulnerable to even small shocks to their incomes, says the report.

In order to overcome the twin problems of poverty and unemployment, the report estimates that the provincial economy would have to grow at seven per cent per annum to effectively dent poverty and provide full employment in the next 10 years or more. This rate, says the report, is well above the average growth of 4.5 per cent a year achieved during 1991-02, and requires changes in the institutional and technological framework of the provincial economy.

The policy makers emphasize that the non-farm, private sector – manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail, and other services – will have to be facilitated by the government to act as engine of growth and create the kind of jobs the economy needs to cope with the formidable challenges of high incidence of poverty and unemployment in the province. For this, the report underscores the need for providing an enabling environment to the private sector by minimizing official interference with the private businesses.

In addition, it also stresses the need for developing and encouraging the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) because this particular sector absorbs more labour force than any other industrial sector. The document also lists several other recommendations to perk up and restructure other sectors of the economy – agriculture, services, construction, etc – as well as overhaul and restructure the finances for creating more jobs and achieving the targeted growth rate of seven per cent to eliminate poverty and joblessness in the province.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM - PUBLISHED AUG 16, 2005

|