|

Closing the gates of Lahore

Sher Ali Khan

Pakhtuns allege discrimination as the government cracks down on terrorism

Illustration by Zehra Nawab

A crowd gathers inside a cool and dark alleyway and a conversation begins to brew in Pashto. Lahore’s Shah Alam Market is a spirited commercial centre and its shopkeepers, selling a panoply of materials and small-scale commodities, seldom have time to gather for idle chitchat. What has brought this group together is the distraught young man at its centre, gesticulating wildly, his national identity card clenched in his fist.

“This card doesn’t say that I am a citizen of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa,” rages Javed Mohmand. “It says that I am a citizen of Pakistan. So why is it that when I went to the bank today, they refused to let me open an account because I am Pathan?”

Mohmand moved to Lahore from Mohmand Agency seven years ago. His family ran a business in Peshawar but shifted to Lahore, hoping to avail a healthier economic climate. He has registered with the local thanas (police stations) three times — every time he switched residence. But this didn’t stop authorities from raiding his Gawalmandi apartment on three separate occasions. Once, a raiding officer insinuated that it was being used for soirees with young men, perpetuating a long-standing ethnic stereotype.

Spurred by the Army Public School massacre and the resulting National Action Plan, police in Lahore have conducted 991 search operations in the city between December 17, 2014 and February 18, 2015; more than 120,000 people have been questioned and 124 cases have been registered, 45 of them under the 1946 Foreigners Act.

But ethnic Pakhtuns and Afghans complain that they have borne the brunt of this newfound vigilance, and unfairly so.

In a recent news report published in Urdu daily Dunya, Lahore’s chief traffic officer Hafiz Cheema was cited as identifying 36 areas deemed high risk for terrorism. Shah Alam Market, Sheranwala Gate, Landa Bazaar and other Pakhtun-dominated areas were all on the list.

“We are targeted because we are Pathan — the state deems all Pathans to be terrorists. If by speaking Pashto one becomes a terrorist, then I, too, am a terrorist,” says Mohmand angrily.

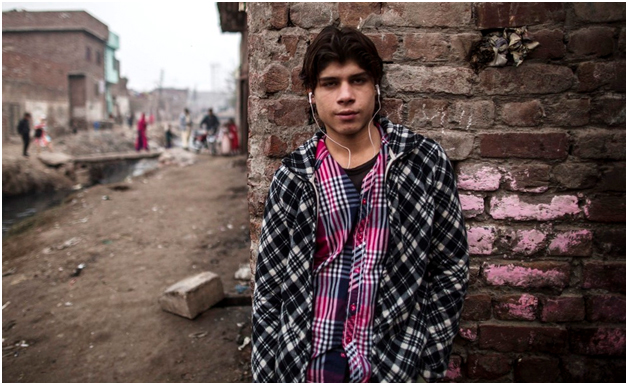

An Afghan girl sorts papers before they are taken to a recycling factory in Lahore | Reuters

Pakhtuns arrived in Lahore in various rounds of migration. Some, such as the forefathers of Zimal Khan, a reporter with Khyber TV, migrated before Partition; others moved to the city in wake of the Afghan War in the 1980s. After the United States invaded Afghanistan in 2001, most Pakhtun refugees opted for cities such as Quetta and Peshawar. Zimal Khan estimates that only between 10 per cent and 15 per cent of Lahore’s Pakhtun migrants arrived during this time. Most live in katchi abaadis near Bund Road and the city’s peripheral areas.

In Landa Bazaar, situated just outside the Lahore railway station, the traders are mostly Afghan, selling shoes, pampers and crockery, as well as anything electronic. Because they give these commodities on credit, they are popular among customers. But the recent crackdown has affected business: Waris Shah, a small business owner, says that he shut down his chappal manufacturing unit only a few weeks ago because of repeated harassment by the police — officials would periodically swoop in, pick up his workers and take them in for questioning.

As Shah relates his travails with the police, his brother Amanullah interjects angrily: “It’s one of those decisions that you come to regret. We had the choice to become Pakistani or remain Afghan and we chose the latter. What a mistake that was!” Their extended family resides in a refugee camp in Nowshera, but Amanullah himself was born in Shahdara, Lahore. “So how can you ask us to go back to Afghanistan now?”

When contacted, Superintendent Police Liaquat Malik tried to downplay the ethnic dimension of the issue. “Look, the Afghans have become a necessary part of our society. If you were to remove them all, some 75 per cent of Lahore’s businesses would disappear. But there are several Afghan bastis (settlements) in Lahore and 28 of them have been marked as sensitive by intelligence agencies. There was no mechanism for data collection for these Afghans, so we don’t really know how many people are living in these areas. It can become an easy sanctuary for terrorists.”

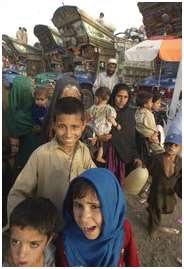

A young boy poses in a slum, in Lahore, inhabited by Afghan refugees | Reuters

Human rights activists claim that the attitude towards the Afghans – and to some extent, all Pakhtun migrants in general – has deeper and more entrenched roots. “There is a word in the dictionary to describe our treatment of Afghan refugees, and that word is ‘xenophobia’,” says Najmuddin of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. “The local population complains that these people take their jobs — if they weren’t around, there would be no unemployment.”

“There are local stakeholders who wish to exploit the situation,” he adds. Indeed, when Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan announced a crackdown on the Afghan basti in Islamabad’s I-11 sector, claiming that it had become a safe haven for terrorists, many alleged that not only was it based on ethnic bias, several local commercial groups also had an interest in its clearing.

It is worth pointing out that in the report on the National Action Plan submitted to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in early February this year, 3,416 Afghans were said to have been deported to their ‘country of origin’. Among these, 2,844 were settled in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 376 in the tribal areas, 195 in Balochistan and one in Islamabad.

According to official figures, therefore, no Afghan based in Punjab has been deported so far. But that hasn’t helped ease the sense of foreboding within the Afghan and the wider Pakhtun community based in Lahore. “There are increasing tensions between the Punjabi traders and Pathan workers,” says Ajmal Khan, head of the Pakhtun Qaumi Ittehad chapter in Shah Alam Market, one of the few representative bodies in Punjab that attempts to address the grievances of Pakhtuns in the province. The emphasis of the group is less on political mobilisation and more on tackling routine issues such as labour disputes and assisting with hospital and funeral bills and registration with local police stations.

“We are still afraid of going to the local thana,” he says, referring to the discriminatory attitude meted out by officials. “But we are increasingly trying to address concerns regarding the treatment of Pathan workers. Our goal is to work with the authorities and ensure that tensions don’t rise further.”

“Pathans in Punjab are like a flock of sheep,” says reporter Zimal Khan. “I get calls in the middle of the night from people asking for help because the authorities have picked up their boys. They spend a great deal of time paying fines and dealing with local officials — but now they are looking to leave. We did an interview the other day with a Pathan businessman who had shifted his business to Turkey. He said Turkey doesn’t treat us as badly as Pakistan does.”

This was originally published in Herald's March 2015 issue

Curtsey::DAWN.COM-May 6,2015-05-06

Humanitarian news and analysis

Gul Hakeem, 52, is a respected shopkeeper in the Shadman Market area of the eastern Pakistan city of Lahore. He is frequently called upon, as a respected elder known for his cool head, to settle minor arguments. His cloth shop in the market's basement area is a favourite gathering spot, not least because of the tales and the jokes Hakeem can tell. He tells them in Punjabi - the dominant language of the city.

Only a slight accent to his Punjabi vowels and his love for freshly brewed green tea gives Hakeem away as an Afghan. While those gathering around him enjoy cups of the sweetened, milky tea, Hakeem pours his green tea from a small kettle into his lacquered cup and allows the aroma of his homeland to drift across the crowded shop as he talks of his days as a young man.

Hakeem came to Peshawar, capital of Pakistan's North West Frontier Province (NWFP), among the first wave of refugees from Afghanistan in 1980, only months after the Soviet invasion of his homeland. He stayed at a refugee camp in the city for a few weeks and then, searching for both adventure and a livelihood, reached Lahore the same year.

"I fell in love with the city," he told IRIN. "In some ways, it reminded me of my home near Herat, even though everything was different. Yet, even though I spoke little Urdu at the time, people were friendly and the resentment against Afghans that came later had not yet set in."

Hakeem did odd jobs for about a year, but by the end of 1981 was able to rent a shop, selling cloth he brought in from Peshawar. He has expanded his business since then, buying the shop he rented in 1990. He married an Afghan woman from another refugee family in 1985 and the couple, with four children all studying at local institutions, plan on staying in Lahore.

"It is my home," Hakeem said. "What happened in the past is now only a part of the stories I tell."

According to Tajammul John Muneer, coordinator of the Afghan Refugees Programme at Caritas in Lahore, the implementing partner for refugee programmes with the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are currently around 7,000 Afghan refugees in the city. He also believes that "at least some among these will go home". A large number of refugees returned home in 2003 and 2004 under UNHCR-assisted programmes.

However, it is also clear that a large number won't. Many of the refugees who came from Afghanistan are now well established in the city and have strong links to local families. They naturally have little wish to close flourishing businesses or abandon jobs to return to a country where economic insecurity and the aftermath of war are still plainly visible.

"Look, the fact is that the Kabul I knew as a young girl is no longer there," said Raheema Bibi, 32, who left Afghanistan with her parents when she was 15. "It is a different place. The families we knew have moved away. So many have been killed that I know no one there."

Her parents have since died in Peshawar. Bibi added: "For me and my three children, this city is where we now want to live. I have parents-in-law and my children's grandparents - as my husband Wali's family is here. They too came from Afghanistan, but are now happy to stay here."

Bibi and Wali still talk to each other in Dari, the first language of both families. However, they speak to their children, Shamsa, 10, Waleed, 8, and Hashim, 5, mainly in Urdu, indicating a break from the past and the start of a new life.

"The older children understand Dari, but they don't speak it," Wali said. "I would like them to learn, but Urdu is more important for them right now."

As Tariq Khan, coordinator of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) in Peshawar and in charge of programmes linked to refugee affairs, told IRIN: "Many of those who came as refugees are now in fact a part of their communities in cities such as Lahore. As with every Diaspora, there are people who move away from their roots and into a new setting, never to return home. It is hardly surprising that should happen in the case of the Afghans as well."

The close linguistic and cultural links between Afghans and Pashtuns made amalgamation easier. However, even in Lahore, Afghans have managed to blend in and in some cases, even married into Punjabi families.

"My parents were not happy when I married Kulsoom," Habib Khan, 33, said. "But then they came to know her and like her. Now that things are calmer, I hope to take her and our son to visit my parents, who are still in Afghanistan, but then we will return to our lives here."

While some Afghans, such as Habib, have moved away from their own communities and into mainstream society in the city, most of those still staying on are based in settlements around the Garden Town area, or Bedian Road, where quarters in "katchi abadis" (slum areas) are made up of Afghans.

The bright, pink and green skirts of the older women, or the blonde hair and green eyes of small children, as they play a game of street cricket with Lahori youngsters, give them away as Afghans, even though many have in fact been born in the city and have never known their ancestral homeland.

Some among these communities say that, even with the UNHCR's help, they are too poor to return. Others seem unwilling to risk the uncertainty and possible economic suffering the shift would bring, happier to continue with the small business or jobs as guards, carpenters or vendors that they have found locally. The reputation of Afghans as good businessmen has also held true, with a large number now dominating markets, such as the cloth bazaar at the Auriga Centre in Gulberg.

These Afghans seem certain to remain a part of the city scene, and are known by the generic name of "Khan", a popular clan-name among Pashtuns and Afghans. Certainly, many among them show little interest in returning. They maintain that the homeland many left as children is now nothing but a distant memory - and that it is in the historic city of Lahore that they now hope to build their futures and bring up their families, with ties to Afghanistan having grown weaker over the years since they left it far behind.

Curtsey:www.irinnews.org

http://www.irinnews.org/indepthmain.aspx?InDepthId=16&ReportId=62527&Country=Yes

|