|

|||||||||||||||||||

Khuda ki Basti (Novel)The partition of India in 1947 was a bloody affair. Thousands of Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs lost their lives in the unprecedented riots and clashes that erupted just as the British colonialists recognised the demand of the All India Muslim League to carve out a separate Muslim homeland for the Muslims of the region.

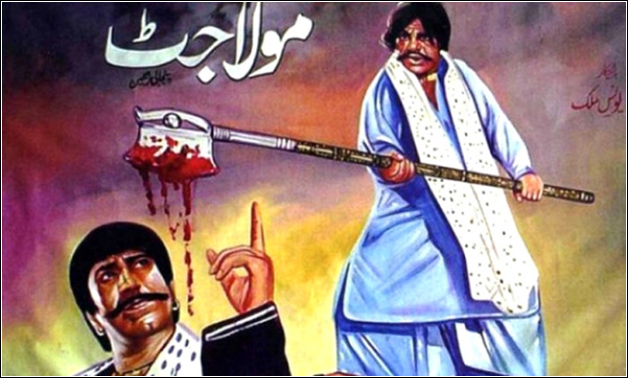

Maula Jatt (Film)

The fall of the ZA Bhutto regime in July 1977 and the taking over of power by a reactionary military general (Ziaul Haq), brought down the curtain on the era of populist social and political extroversion.

The anti-hero growls …

The damsel sings …

And the tyrant falls … 12 songs from Pakistan’s mountains, deserts, shrines and streets

|

|

Mai Bhagi was born in 1920 in a small village surrounded by the vast and unforgiving Thar Desert. She began to sing Thari songs as a child.

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, Bhagi’s family began to regularly travel to Pakistan’s largest city (and future capital of Sindh), to earn some money by singing at marriage ceremonies of Sindhi families residing in Karachi.

It was at one such ceremony that a producer associated with Radio Pakistan noticed a then 30-something Bhagi and offered to record some songs by her in the studios. She was paid a check of Rs.20 for her efforts.

By the early 1960s, Mai Bhagi was regularly appearing on Radio Pakistan singing songs in Thari and Sindhi languages, but she remained rooted in her small and impoverished village in Tharparkar.

It is believed that though she had been singing ‘Kharee neem kay neechey’ ever since she was a teenager, she first sang the song on Radio Pakistan sometime in the early 1960s.

But it wasn’t until she sang it on the state-owned PTV in 1974 that the song became a national mainstream hit and turned Bhagi into a Sindhi/Thari folk star.

The song speaks of a dreamy young woman of the desert standing underneath a neem tree, watching the sands of time roll by, as Thar’s ‘national bird’ (the peacocks) and koels dance and sing around her, becoming Mai Bhagi’s main claim to fame after she performed it on TV.

She soon began to accompany a number of other folk singers who were often sent to various countries by the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to perform at ‘folk concerts’ and ‘folk melas’ in cities like New York, London, Moscow, Paris, etc.

Bhagi was already in her 50s when she first gained widespread national recognition in the 1970s. She continued to perform the song in concerts and on TV until her death in 1986 at the age of 66.

Ya qurban by Zarsanga

The history and tradition of Pashtu folk music is almost as ancient as the history and origins of the Pashtu people.

Though, most experts place the origins of the Pashtu language and culture in the first millennium BC, Pashtu folk music that started to gain mainstream recognition in the 20th Century (in Afghanistan, India and then Pakistan), most probably began to develop in the region 500 years ago.

There are conflicting theories about the origins and evolution of Pashtu folk music, but there is widespread agreement that though throughout its history, music in Pakhtun culture was largely seen as a personal hobby and vocation of Pakhtuns belonging to the ‘lesser tribes’, it began to emerge more strongly during the Pakhtun Durrani Empire in Afghanistan (18th-19th Century) that laid the initial seeds of what would develop into becoming modern Pakhtun nationalism and identity in the 20th Century.

As a consequence, Pakhtun folk music became increasingly linked to expressing and romanticising the rugged geography of the Pakhtun-majority regions in South Asia and the culture of its people.

Interestingly, though both, the 20th century secular Pakhtun nationalists, as well as the more religious and conservative expressions of Pakhtun identity, celebrated the Pakhtun culture’s militaristic tenor, Pakhtun folk music is remarkably romantic and poetic in nature, with the singers mostly voicing sagas of longing for their beloveds (who are in some foreign land), or for the mountains and rivers of the Pakhtun lands that the singer misses.

Pakhtun folk music was already popular among the Pakhtuns of Pakistan after the country’s creation in 1947.

Pakhtun singers that emerged in Pakistan also gained popularity among the Pashtu-speaking population of Afghanistan (and vice versa).

|

When in the 1960s and 1970s the government(s) in Pakistan began to ensemble folk musicians from the country’s main ethnic groups, who used to often accompany the country’s rulers on foreign trips, one of the most famous Pashtu vocalists to emerge during this period was a young Pakhtun woman called Zarsanga.

Zarsanga was born in 1946 into a nomadic tribe in Laki Marwat in the present-day Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). The tribe’s main vocation was singing, so Zarsanga began to sing at an early age.

She would travel with her tribe all over Pakistan and even to Afghanistan where the tribe would settle in the summers. By the time she got married in 1965 at the age of 19, she was already a famous singer among the Pakhtuns of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Most of the songs that she sang were written by the common people of her nomadic tribe. The songs spoke about the joys and tragedies of the lives of Pakhtun gypsies.

The non-Pashtu sections of the country discovered her when she began to record songs for Radio Pakistan in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

One such song, ‘Ya Qurban,’ was regularly played by the station so much so that a French employee of Radio France who was visiting Pakistan at the time was so smitten by Zarsanga’s voice, she decided to meet her.

After watching Zarsanga perform at a folk concert in Peshawar, Radio France offered to pay for her visit to France where Zarsanga sang to a captivated audience of French men and women.

Radio France introduced Zarsanga as ‘the mountainous voice of the Pakhtuns.’ Between the 1970s and 1990s, Zarsanga was regularly invited to perform in various European countries, and though militant violence in the last decade or so in KP has drastically scaled back the further development of Pashtu folk music, Zarsanga (now 67 years old), still manages to perform whenever she gets the chance (especially on private Pashtu TV channels).

Laila O’ Laila by Faiz Mohammad Baloch

One of the most well-known and loved musical characters to represent Pakistan’s troubled province of Balochistan remains to be singer and musician, Faiz Mohammad Baloch.

But it was not in Balochistan from where he began his career in music. Born in an Iranian-Baloch family in Iran, he was taught to play various indigenous Baloch musical instruments and to sing by his father.

Faiz was already 46 years old when he moved with his wife and children to the newly created country of Pakistan in 1947. Here, he settled in the congested working-class area of Lyari in Karachi that had a sizable Balochi-speaking population.

He worked as a labourer by the day and in the evenings he would entertain the people of the area with his singing and music in street corners and at weddings.

In the 1950s, he began to record his songs for Radio Pakistan but mainstream fame continued to elude him, though he became popular among the Balochi-speaking segments of Karachi.

|

Radio could not capture the full potential of his performances that included dancing (barefooted) while singing. Most of his songs were upbeat and jolly odes to elusive love interests. The music was purposefully set and composed to attract the popularity that traditional Balochi dance enjoyed among the working-class Baloch youth of Lyari.

‘Laila O’ Laila’ was one such song and it was the performance of this delightfully upbeat ditty by Faiz on PTV that finally propelled him into the corridors of mainstream fame.

His popularity had not progressed beyond being a standard item in Lyari and at weddings. And in spite of the fact that he was (by the 1960s) regularly recording songs for Radio Pakistan (in Karachi), he decided to move to Quetta (the capital of Balochistan).

In 1974, Quetta was given its own studios by the state-owned Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV), and this was one of the reasons why Faiz moved to that city.

The same year he began to regularly appear on PTV but it was his performance of ‘Laila O’ Laila’ in a PTV show in 1973 that turned this now 73-year-old Baloch singer into an almost overnight folk music sensation.

Faiz also began to tour various European countries, the former Soviet Union and the United States with government-funded troupes of Pakistan’s ethnic folk singers.

Once in 1975 in New York where he was performing at a ‘Pakistani Folk Music Mela’ organised there by the Pakistani Embassy, he left the audience fascinated. People were curious to find out how a 74-year-old former labourer could perform the way he did, dancing and singing with such joy.

After the concert an American reporter asked Faiz what he thought about the Baloch nationalist insurgency that was taking place in Balochistan (against the populist government of Z A. Bhutto and the state).

Faiz showed the reporter some of his fingers that seemed to be infected. He said (in Balochi), ‘I was a labourer for most of my life. I broke my fingers a number of times while lifting bricks, and yet I used to come back and play (string) instruments and make music with these very fingers. These fingers have never pulled the trigger of a gun. My people are a peaceful people.’

Faiz was bestowed by numerous awards by the government and as he got older, demand for his songs and concerts increased. But alas, old age finally began to take its toll and Faiz became bedridden in 1978.

He passed away in Quetta in 1982.

Sada chiriyaan da chamba by Tufail Niazi

Tufail Niazi was the quintessential Punjabi folk music act. As a genre, Punjabi folk music tries to comment on and reflect almost every facet of the Punjabi culture; especially the one found in the Punjab’s many small towns and villages.

Just like Sindhi folk music, Punjabi folk music too, is largely steeped in the area’s Sufi ethos and widespread ‘Sufi shrine culture.’ But in the last century or so, Punjabi folk has often incorporated (within the traditional Sufi ethos of the songs), social themes such as the exploitation of the peasants (by the landed elite, the clergy, etc.); and the celebration of the everyday (and simple) lives of village people.

Though Punjabi folk music is mostly perceived to be about songs and music constructed to encourage traditional Punjabi dances such as the bhangra and the dhamal, a significant part of the genre is also about expressing the highly emotive aspects of the lives of the common Punjabi villagers regarding their association with various social, religious and marital rituals and ceremonies.

|

Niazi was fully apt to perform songs of joy about harvest time in the villages, and deep Sufi anthems and ‘kafis’, but one of his most popular tunes turned out to be a song depicting the emotional disposition of a young bride who was about to leave her parents’ home to start a brand new life in another house and family.

The song, ‘Sadaa chiriyaan da chamba’ (Our House of Birds) that was first performed by Niazi in the 1960s became a mainstay in various Pakistani films and TV plays during scenes where the bride was about to depart her house with her husband (Ruksati).

It is interesting to note that the song that Niazi sang in a highly emotive tone and tenor was never out-rightly explained by him to be a wedding song. In it, he liberally uses Sufi imagery, explaining the bride as a bird destined to fly away from those who had so lovingly nurtured it.

Though Niazi was equally famous for his more upbeat songs, he bagged a massive following when he introduced a more melancholic side to his singing.

Born in Jalandhar (which today is in Indian Punjab) in 1916, Niazi was drawn to music at an early age and often performed Punjabi folk tunes for the town’s large Sikh population and at Gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship).

He soon moved on to performing on the streets for some money, supplementing his performances with theatrics. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, he moved to what became Pakistani Punjab and settled in the city of Multan (also known as the ‘city of Sufi saints and shrines’).

But his music could not draw as much attention here. Disappointed by this, Niazi began to work at a small milk shop in Multan.

However, a policeman who had seen him perform on the streets of Jalandar and Goindwal, helped him buy a few musical instruments and encouraged him to start performing again.

Tufail started to steadily develop a following when he began to sing Sufi kaafis at Multan’s many Sufi shrines.

By the early 1960s, he had become a mainstay at shrines across the Punjab and at the homes of his growing number of fans.

In 1964 when the government of Ayub Khan launched the country’s first television station and transmission, Niazi became the first singer to sing for the channel (PTV).

His popularity as a Punjabi folk singer peaked in the 1970s during the populist regime of Z A. Bhutto whose government (as a matter of policy) heavily invested in the mainstream proliferation of Sindhi, Pashtun, Punjabi and Baloch folk music.

He also worked closely with Dr Uxi Mufti in setting up and developing the National Institute of Folk Heritage.

In the 1980s, Niazi’s health began to suffer and he stopped performing after suffering a stroke. Unfortunately, during his last years he had lost his income and savings and when he died in 1990, he had already fallen into poverty.

Inshah ji utho by Amanat Ali Khan

An accomplished and experienced Eastern Classical singer and musician, Amanat Ali Khan, however, found fame as an Urdu ghazal singer.

Coming from a family of Eastern Classical musicians, Amanat often performed with his brother on Radio Pakistan and in private gatherings.

He shot to mainstream fame when he used his highly soulful and somewhat forlorn voice to sing ghazals authored by famous Urdu poets.

Amanat Ali scored a number of hits between the late 1960s and early 1970s. But it was the year 1974 that was the most significant because in it he notched three massive hits (via PTV) but then suddenly died. He was at the peak of his talent and popularity when he passed away in late 1974.

Out of the three major hits that he scored in 1974 (Hotoun pay kabhi unkay,Chaand meri zameen and Inshah ji utho), the last one greatly propelled his reputation and fame and (along with Mehdi Hassan), he became perhaps the only other Pakistani classical singer to gain mainstream popularity.

But unlike Hassan, Amanat did not sing for films. He might have gone on to had he lived longer, but he was very selective and finicky in choosing the poets whose work he was willing to use whenever he decided to depart from his classical roots and adopt the semi-classical Urdu ghazal genre.

|

Urdu poet Ibn-e-Inshah caught Amanat’s interest and attention when he wrote ‘Inshah ji utho’ (Get up, Inshah ji). Amanat was looking for words that would depict the pathos of urban life (in Karachi and Lahore).

Someone handed him Ibn-e-Inshah’s ‘Inshah ji utho’ and Amanat immediately expressed his desire to sing the poem. He met Inb-e-Inshah in Lahore and demonstrated how he planned to sing the ghazal. Inshah was impressed and believed that Amanat actually transformed himself into becoming the protagonist of the poem.

The ghazal poem is about a broken man who after spending the night at a gathering of lonely men (most probably at a bar or a brothel), suddenly decides to get up and leave (not only the place but the city itself).

He walks all the way back to his house and reaches it in the wee hours of the morning. He wonders what excuse he will give to his loved one.

He’s a misunderstood man looking for meaning (in what he believes) is a meaningless existence.

When Amanat first performed the song on PTV in 1974, the channel was bombarded by letters and phone calls demanding that it be played over and over again.

Alas, Amanat’s biggest hit also became his last as he suddenly passed away at the age of 52.

Tragically, Ibn-e-Inshah too passed away almost as suddenly in 1978 at the same age (!)

Video | Amanat Ali Khan performing 'Insha ji utho' on PTV in 1974:

Humma Humma by Allan Fakir

Allan Fakir was one of the foremost Sindhi folk musicians. He specialised in singing devotional Sufi songs. The Fakir in his name stands for the impassioned drifters who for centuries were/are a regular fixture outside the shrines of Sufi saints in Sindh and the Punjab.

Born in a small village near the city of Jamshoro in the Sindh province, Allan began his musical journey as a singer who would play celebratory songs with his father and brothers at weddings.

|

As a rebellious young man he had a falling-out with his father and decided to leave home. In 1950, he walked all the way to the shrine of famous Sufi saint, Shah Abdul Latif, in the small town of Bhit Shah. He began to live among the fakirs on the streets just outside the shrine.

At the shrine, he was introduced to the flowing (Sindhi) poetry of Shah Latif. He could often be seen singing Latif’s poems.

His unique style of delivering the saint’s message, using his singing voice, dance and quirky stylistic diversions in which he would suddenly let out strange sounds to express the ecstasy that he was feeling, turned him into a popular attraction for the hundreds devotees that used to visit the shrine on a daily basis.

For almost a decade and a half Allan lived a life of a penniless fakir camped outside the shrine till he was discovered by a producer of Radio Pakistan and invited to record a few Sufi songs for the state-owned channel.

Allan became a regular on PTV at the peak of the government-backed mainstream boom enjoyed by Pakistan’s folk music scene during the populist regime of Z A. Bhutto (1971-77).

Though, Allan would go on to score several hits (all based on Sufi themes), one of his most impassioned, quirky and popular songs was ‘Humma Humma.’

Sung in Sindhi and borrowing portions from Shah Latif’s poems, Allan had improvised and honed the song during his years as a fakir outside Shah Latif’s shrine.

For the mainstream audience, he first performed the song at folk music festivals and on PTV in the 1970s and by the early 1980s it had become one of the most demanded songs at his performances.

Allan’s most passionate performances, however, remained to be the ones that took place during the birth celebrations of Shah Latif and another famous Sufi saint, Lal Shahbaz, at their shrines in Bhit Shah and Shewan Sharif respectively.

He would always conclude his concerts with ‘Humma Humma’, singing it with reckless abandon because the song itself was about a fakir going against the tides of the material world and joyfully plunging into those inexplicable dimensions of space and time where he would directly feel the presence of his beloved (God).

In 1983, when Sindh erupted into a violent movement against the Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-89), Allan was asked by radical Sindhi nationalists to stop performing on PTV.

And when a group of Sindhi nationalists asked him to perform at a rally (in Hyderabad), Allan was warned by the government to stay away.

Allan decided to stay away from both the PTV, as well as the nationalists, but on the eve of the rally he was picked up by the radicals and forced to perform at the demonstration.

In 1985, Allan rebounded and agreed to TV actress-turned-producer, Saira Kazmi’s idea of turning his popular ‘Humma Humma’ anthem into a fusion-pop number.

He performed the song on PTV with the time’s famous pop star, Mohammad Ali Shaikhi. The song pushed him into becoming perhaps the most well-known and popular Sindhi folk singer in the country.

In the 1990s, Allan’s mainstream popularity began to decline, but he continued to perform at shrines till he passed away in 2000 at the age of 68.

Video | Allan Fakir performing ‘Humma Humma’ at a concert in Bhit Shah in 1984:

Dasht-e-Tanhai by Iqbal Bano

Faiz Ahmed Faiz was arguably one of the greatest Urdu poets of the 20th century. A communist, he was also a journalist.

Faiz was already a famous poet when he was arrested (along with dozens of army officers and communists) in 1951 for plotting a coup against the government of Liaquat Ali Khan.

After his release, Faiz struggled to find a job in newspapers but continued to write poetry that was rich in symbolisms pitched against tyrants, dictators, capitalists and religionists.

Unlike Habib Jalib, another communist poet who used simple Urdu and populist imagery in his poems, Faiz continued to demonstrate his creative command over the Urdu language.

During the Z A. Bhutto regime the state-owned PTV decided to give some of Faiz’s poems a singing voice, but it struggled to find one that could convincingly capture and deliver the rich Urdu and imagery found in Faiz’s works.

A PTV producer who was responsible for producing the channel’s weekly semi-classical music show, ‘Nikhar’ was reminded of Iqbal Bano by a colleague.

Bano was an Eastern Classical and ghazal singer. She had also recorded songs for some Pakistani films in the 1950s. In the 1960s, she had begun to sing a couple of Faiz’s poems at private gatherings.

|

The PTV producer saw her singing one such song at a friend’s house and immediately invited her to his show. Bano had already honed the singing of one of Faiz’s most melancholic poems, ‘Dasht-e-Tanhai’ (The Desert of Solitude) when she performed it on PTV in 1974.

Though, Bano had enjoyed some fame as a film playback singer in the 1950s, after she sang ‘Dasht-e-Tanhai’ on PTV, she suddenly became immensely popular among the fans of Urdu ghazal.

The beauty of Bano’s delivery of ‘Dasht-e-Tanhai’ is in the way she brilliantly captures and expresses the melancholic feeling of longing present in the poem.

Though, Faiz is apparently longing for a loved one in a moment of solitude, many suggest that he is actually talking about his experience as a prisoner (in jail) where the memory of his loved one eases the pain of his loneliness.

This song became Bano’s main claim to fame. In fact, she would go on to become an expert at singing Faiz. In 1985, at the height of Ziaul Haq’s reactionary dictatorship, Bano’s musical rendition of Faiz’s revolutionary ‘Hum daikien gey’ (We Shall See) at a large concert in Lahore almost started a riot against the Zia regime.

Bano passed away in 2009 at the age of 74.

Video | Iqbal Bano performing ‘Dasht-e-Tanhai’ on PTV in 1974:

Manda ishq vi toun by Pathanay Khan

Pathanay Khan was perhaps the most well-known folk singer emerging from the Seraiki speaking region of the Punjab.

Born in a small village in the Bahawalpur district, Khan’s early years were ravaged by poverty. His father died early and he tried to make a bearable living by collecting firewood for his mother, who then used the wood to bake bread for the village people.

His mother tried to get him an education, but Khan quit school and began to wander outside Sufi shrines. He particularly got attached to the kafis and poetry written by 19th century Sufi saint Khwaja Farid.

After his mother’s death, Khan began to sing Farid’s poetry at the saint’s shrine in Bahawalpur. He almost immediately developed a following among the shrine goers who fell in love with his forsaken style of singing.

|

Pathanay Khan was first introduced to a more mainstream audience in the 1960s through Radio Pakistan. Then, in the 1970s, he began to occasionally appear on PTV. But his main area of performance remained to be at Farid’s shrine in Bahawalpur.

Khan’s reputation as a touching and heart-felt Seraiki singer of Sufi poetry travelled all the way to Prime Minister Z A. Bhutto who (in 1976) invited him to the capital Islamabad to perform for him.

Khan performed three songs for the PM, one of them being ‘Manda ishq bhi toun’ (You Are My Love Also) – a rousing rendition of Farid’s ode to the Almighty, celebrating Sufism’s inherent and indigenous pluralism.

This song, in fact became Pathanay Khan’s most famous creation, especially when he began to perform it on PTV from 1981 onwards.

In the late 1990s due to ill health, Khan almost stopped performing and in the year 2000 he passed away. His funeral was attended by thousands of his admirers.

Video | Pathanay Khan performing ‘Manda ishq bhi toun’ on PTV in 1981:

Hai rabba nai lagda dil mera by Reshma

Reshma was one of the most recognised and popular female Punjabi/Seraiki folk singers in Pakistan. At the peak of her popularity between the 1970s and early 1980s, her fame could even match that of the most famous mainstream film ‘playback singers’ and pop musicians of the country.

|

Born on the eve of the creation of Pakistan in 1947 in a desert village of Rajahastan, Reshma’s family moved to Pakistan and settled in the new country’s sprawling metropolis, Karachi.

Reshma’s family belonged to a gypsy tribe and it wandered the Sufi shrines of the city and the rest of Sindh, performing songs for anyone interested to pay them a few paisas.

She was discovered as a teenager by a radio producer while performing for a small crowd at the shrine of Lal Shahbaz in Sindh’s Sehwan Sharif. The producer was impressed by her voice that was extremely deep and heavy, making her sound much older than she actually was.

From radio, Reshma quickly graduated to performing on TV, and when she sang the populist Sufi anthem ‘Laal meri pat’ (a rousing ode to the Sufi saint, Lal Shahbaz) on PTV in 1967, she was able to attract immediate attention.

Across the 1970s, she became the leading female folk singer and voice on TV. By the mid-1970s she also began to receive offers from film producers to sing for the then thriving Pakistani film scene.

But Reshma stuck to recording albums for EMI-Pakistan, performing on TV and at large Pakistani folk festivals, both in the country and abroad.

By now, she had also begun to sing Urdu songs. These too were delivered through her uniquely deep and heavy voice.

One of her most melodious and touching Punjabi folk songs is ‘Hai rabba nai lug da dil mera’ – a song about a heartbroken village girl who, after losing a beloved, can’t figure out what she would do without him. She tries, but fails, asking the Almighty what it was that she was supposed to do now.

The song was recorded for PTV in 1975 and it was this song that would lead to a sequel of sorts in the 1980s (‘Lambhi jodaai’) that was picked up and used in the Indian film, ‘Hero’ in 1983.

Reshma was now at the peak of her fame and constantly praised for bearing a unique voice and style of singing. Alas, in a cruel twist of irony, she was diagnosed of having throat cancer.

Consequently, the number of her performances began to decline and by the late 1980s she was hardly singing at all. Nevertheless, she managed to fight her cancer for a long time. In 2013, she finally lost the long battle and passed away at the age of 66.

Ay puttar hataan tey nai vikdey by Noor Jehan

Noor Jehan had a remarkably long career as a popular singer in which, for almost four decades she was able to sustain her status of being Pakistan’s most loved female vocalist.

She began her career as a singer and actress in films in undivided India. After Pakistan’s creation in 1947, she quickly rose to become one of Pakistan’s leading vocalists, actors and a heartthrob.

She gave up acting in the 1964, but continued to record songs for Urdu and Punjabi films. During the 1965 India-Pakistan war, she added a new dimension to her singing career when she recorded a special song for Radio Pakistan and the then nascent PTV, composed and worded to inspire the armed forces.

|

During the recording of this song (‘Ay watan kay shajeel-e-jawanoun’), she broke down and tears began to roll down her cheeks. The producers decided to keep the TV cameras rolling and the song was instantly embraced by a nation at war. The war itself ended in a stalemate.

Noor Jehan was invited by PTV to record another patriotic song when Pakistan and India once again decided to go to war in December 1971. This time Noor Jehan arrived with a song in Punjabi – ‘Ay puttar hataan tey nai vikdey’ (These sons are not for sale – because they are a gift of the revered Sufi saint, Data Ganj Shakar).

Though, Pakistan lost the conflict, Noor Jehan’s song became immensely popular during the war. It was constantly played by young soldiers posted across the country’s borders.

After the war, the song was adopted by the Pakistan hockey team that rose to become one of the leading field hockey sides in the world in the 1970s and early 1980s.

During a pre-match report on PTV before the start of the final between Pakistan and India in the 1974 Asian Games in Tehran, Noor Jehan’s song was heard being played in Pakistan’s dressing room.

After recording hundreds of Urdu and Punjabi songs between the 1950s and 1990s, Noor Jehan passed away in 2000 at the age of 74.

Video | Noor Jehan performing ‘Aye puttar’ on PTV in December 1971:

Paani da bulbula by Yaqoob Atif

In the early 1970s, singer Yaqoob Atif, created a contemporary Punjabi folk tune that had little to do with rural themes or Sufi traditions. Instead, he successfully worded, composed and sang perhaps Punjab’s first urban folk ditty, swarming with witty and tongue-in-cheek references and the imagery of city life and urban culture of the populist 1970s.

He called his song ‘Paani da bulbula’ (A Bubble of Water). The song is a joyful compilation of observations of a street-corner philosopher who insists that life is just a bubble of water, which is fragile and could burst anytime so one should enjoy it as much as one can by eating, drinking and having a ball!

|

The song gallops along at a bouncy pace by rapping and rhyming Atif’s short takes on things that cramp city life, new and old, modern and traditional. It also includes a reference to the populist Socialist Zeitgeist of the period when the singer refers to the ZA Bhutto regime’s famous ‘Roti, Kapra, Makan’ (Bread, Clothing, Housing) slogan.

Atif recorded the song for various small recording studios. It became a huge cult hit in the cities and towns of the Punjab. It enjoyed mainstream fame when in 1979 a part of it was played in PTV’s famous drama serial, Waaris.

In 2013, the song was revived by directors Farjad Nabi and Meenu Gaur for their independent film, ‘Zinda Bhaag.’

Though the song has been around since 1973, its creator never did make much money from it. However, his name did eventually evolve from being Yaqoob Atif to becoming Yaqoob Atif Bulbula!

Video | A 1975 audio recording of Yaqoob Atif’s ‘Paani da bulbula’:

Hai kambakht tu nein pi hi nahi by Aziz Mian

The 1970s and 1980s were the golden age of Qawali in Pakistan – ancient Sufi devotional music that originated in Iran 700 years ago but thrived the most in South Asia.

Though, it remained popular here, its first true manifestation as a commercially viable art-form emerged in Pakistan between the 1970s and the early 1980s.

Aziz Mian and the Sabri Brothers became the two most popular and commercially successful Qawali acts in Pakistan, followed (in the late 1980s and 1990s) by the likes of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan.

Among these giants, Aziz Mian became the most controversial. By the mid-1970s, Aziz Mian had risen to become the region’s leading Qawal and was selling out concerts across Pakistan and India.

However, many of his concerts used to also disintegrate into drunken brawls when Aziz Mian would purposely work up the audience into a state of frenzy and in which many among the crowd would lose all sense of order and control.

Aziz Mian would explain this as being a step from where the brawling men could take the leap into the next stage of making a direct spiritual connection with the Almighty.

|

A cultural writer reviewing one such Aziz Mian concert in Karachi (in DAWN) in 1975, described him as being ‘the Nietzschean Sufi!’

The Sabri Brothers on the other hand, were a lot more melodic and hypnotic in their style and also began drawing huge crowds.

Soon, a rivalry began to develop between Aziz Mian and the Brothers.

The Brothers often mocked Aziz Mian for being violent and lacking melody and of being a drunk.

Aziz Mian and the Sabri Brothers both stood for the same Sufi traditions and narratives that had developed in the region, but the Brothers disapproved of Aziz Mian’s open praise of alcohol in his Qawalis – even though alcohol was often consumed at the Brothers’ concerts as well.

Aziz Mian was quick to retaliate. In 1975, he wrote and recorded ‘Hai kambakht, tu nein pe hi nahi’ (Unfortunate soul, you never even drank) in which he derided the Brothers for not understanding and never experiencing the ‘spiritual sides of wine.’

A 30-plus-minutes opus, the Qawali starts by Aziz proudly owning up to liking his drink and then suggests that those who don’t drink and give lectures on morals but indulge in other misdeeds are hypocrites. All the while, he continues to taunt the Brothers for never having experienced wine.

In the long climax of the Qawali, Aziz Mian’s taunting turns into anger and he dismisses his detractors (and the Brothers) for not understanding his intoxicated love for the Almighty because they have no clue what it meant or felt like.

Aziz Mian’s fame began to fade in the late 1980s but he continued to perform right till his death (from liver failure) in 2000.

Video | First audio recording of 'Hai kambakht’ by Aziz Mian (1975): This article is dedicated to former Editor of Dawn.Com, Musadiq Sanwal - friend, folk singer and the man who enabled me to find the true beauty of Pakistan's various folk traditions and arts. God bless him.

Curtsey:DAWN.COM UPDATED MAY 15, 2014

Gullu Butt: An Auto-smashing-biography

NADEEM F. PARACHA

Gullu Butt — a smashing success in the auto industry. — Photo by INP

Gullu Butt is a famous automobile smasher from Pakistan. He was born in Lahore (capital of the Punjab province) to equally famous parents, Maula Jatt and Nuri Nutt. His father, Maula Jatt, was the sheriff of a small town in the Punjab and gained popularity for arresting, jailing, flogging and dismembering a pesky motorbike that just won't start.

After dismembering the bike, Jatt set it on fire, much to the liking of the simple peace-loving townsfolk. Jatt, however, became unpopular when he tried to do the same to a horse. He was expelled from the town by the Chaudhry of the town (town elder) along with his wife, Nuri Nutt.

|

Jatt right after smashing the motorbike (1974) |

Jatt and his wife moved to Lahore in 1975 and earned a meagre living by selling old spare-parts of the cars and bikes that Jatt would smash and dismantle just for the heck of it. Jatt's antics in this regard got him arrested and he was sentenced to 10 years hard labour in a Lahore jail.

Meanwhile, Nuri Nutt gave birth to their first child whom she named Gullu Butt (Rosy Butt- cheeks). Two years later Jatt was paroled and gained an early release from jail, thanks to the government of General Ziaul Haq who had taken over power in July 1977. The Zia regime considered Jatt to be a political prisoner, arrested by the fallen ZA Bhutto regime.

|

Jatt soon after he was released from jail (1977) |

To celebrate his early release, Jatt smashed a car belonging to a member of Bhutto's party as the people and the police stood there watching the spectacle and marvelling at the might and passion of Jatt.

|

Jatt right after smashing a car belonging to a PPP member (1978) |

Jatt and his wife were invited back to their hometown where the Chaudhry (who had quit Bhutto's party and joined the Zia regime) himself offered Jatt a horse to dismember. Instead, Jatt broke the Chaudhry's legs and once again ended up in jail. There he met Bhutto and proceeded to hang him, much to the liking of peace-loving jail folk.

Meanwhile, Nuri Nutt gave birth to their second child. She named him Jeera Blade (Gillette Razor). As Jatt lay rotting in jail, Nutt had to bring up their two sons all on her own. Sometimes when she could not earn enough money to feed and cloth her sons, she used to digress and commit theft by raiding the town's shops with a home-made rifle.

She soon became notorious and the scared townsfolk began to inexplicably call her Hasina Atombum. Nutt wanted both of her sons to get a good education and become dentists.

Jeera was an obedient son and a hard-working student and always came second-last in his class. But Gullu did not take his studies seriously. He would spend most of his time painting a fake moustache with a thick black 2B pencil on his face and smashing watermelons on the Chaudhry's farm.

|

Nuri Nutt: The crime-spree years. |

After passing his matriculation (in 3rd division), Jeera tried to join the Lahore police but failed the test. He was however given an officer's post in the Lahore police after the Chaudhry pulled some strings. Gullu had threatened to beat up the Chaudhry's favorite horse.

After Jeera joined the police, Nutt stopped being Hasina Atombum. She even asked Gullu to join the police but Gullu refused. Instead, Gullu smashed the car of a small-time crook, an act that impressed a big-time crook who asked Gullu to join his gang.

The big-time crook was a gunrunner who smuggled in guns, drugs, rockets, grenades and Italian caviar from the Afghan border where he had connections with the anti-Soviet Afghan insurgents and some members of Zia's government.

Once while Jeera was fleecing a milkman on a Lahore street and asking him to pay Rs.50 or face jail, he spotted Gullu smashing a brand new car. He rushed to the spot and asked Gullu to stop.

Gullu asked: 'Merey pass jackhammer hai, cars to smash haen, plug-pana hai, tumarey pas kya hai?'

Jeera replied: Merey pas maan hai (I have mother).'

The crowd that had gathered around them applauded and some people even had a tear or two in their eyes.

Jeera and his mother shunned Gullu who had by then smashed and destroyed over 2,000 cars just for the heck of it.

Meanwhile, Jatt had acquired some basic education in jail and re-discovered faith. After he was released in 2001, he first set-up a madrassah in Lahore (which was a huge spiritual, ideological and commercial success), and then joined a TV news channel as an anchor and talk-show host.

Jeera rose to become an ASI in the police (only because his tummy was the biggest the precent) and Nutt went nuts, now claiming she was Madam Noor Jehan. She was recruited by PTI trolls.

Gullu continued to smash cars (still just for the heck of it), but from 2005 onward he tried to give a semblance of meaning to his art by smashing cars and bikes during anti-US/India/Rwanda rallies and during protests against Pakistan's gazillion enemies - especially Godzilla nurtured by famous Zionist scientist, Amrish Puri.

But, alas, this great artiste's luck finally ran out when in June 2014, while he was in the process of smashing his 5,000th car (to set a new Shahbaz Sharif-backed Guinness World Record), some jealous folks claimed that he was one of the instigators of violence against the supporters of Canadian Moose-breeder, Tahir-ul-Kennedy.

|

Tahir-ul-Kennedy taking a leisurely walk outside his home in Canada. |

Gullu was arrested and booked for injuring a Toyota car and then he was himself injured when he was attacked by a group of lawyers who were otherwise famous for showering rose petals on heroic killers.

Gullu's fan-club, 'Gullu Kay Pathey', at once initiated a powerful campaign on Twitter against Gullu's arrest with such hashtags: #JusticeForGullu; #WeAreAllGulluToday; #ButtHe'sInnocent; and #JustinBieberForPresident.

Just for the heck of it.

CURTSEY:DAWN.COM JUN 20, 2014

CM Punjab’s admirable moves against vulgarity

NADEEM F. PARACHA

In his last stint Punjab Chief Minister, Shahbaz Sharif, had said that vulgarity and obscenity in the name of culture would not be tolerated and strict action would be taken against those ‘de-tracking’ the younger generation.

CM Punjab, Shahbaz Sharif, gestures after scoring another victory against vulgarity.

In his recent stint as Punjab CM he has not only reiterated his stance on vulgarity but has also warned NGOs not to impart ‘sexual education in schools’.

He also constituted a high-level committee headed by the chief secretary to take action against those who violate rules by performing vulgar dances on stage and TV and has asked people to keep an eye on NGOs introducing ‘indecent sexual education’ in the syllabus.

This is a wonderful initiative taken by the Punjab CM. Especially in a pious city like Lahore, where people don’t have sex and babies just fall on mothers’ laps from the sky.

A pious Lahore daddy about to catch a baby falling from the sky.

In fact, the Sindh CM, Qaim Ali Shah, should also follow suit. Otherwise cities like Karachi, Hyderabad and especially Tando Adam are in danger of becoming some of the most obscene and vulgar cities of the world (in fact the whole universe), with naked five-year-old kindergarten children discarding their pampers and indulging in vulgar dance moves on Nickelodeon.

A rebellious kindergarten student going wild after being given vulgar education by scheming NGOs in Lahore.

Our leaders should realise that in Karachi too, people are always indulging in vulgar dances and irresponsibly imparting sex education in schools.

Like, for example, only last Friday night the moral minority of Karachi was shocked when throngs of young men and women got drunk, poured out and started to dance on the roads of the posh Lyari area which is already known for its steamy discos, nightclubs, bars and cafes where so-called intellectuals exchange atheistic ideas over glasses of beer, brandy and bhang. Sometimes all at once.

A group of secular intellectuals making suggestive dance moves outside a discothèque and bar in Karachi’s posh Lyari area.

However, the most infamous chain of clubs in Karachi remains to be the notorious Nite Keelab.

This was also the club that was used by wicked film-makers in the 1970s. It was because of the activities of this club that staunch fans of Pakistan’s founder Jinnah, the Jamat-i-Islami, started a movement against the immoral Z A. Bhutto regime.

If they hadn’t done so, every Pakistani teenage girl would’ve been announcing, “Daddy, I go play badminton and dance in keelab,” on a regular basis and become a roving, rootless hippie chick, smoking hash and telling her elders “Oh you shut up, you nonsense!”

Two immoral Karachiites at the infamous Nite Keelab where inexplicably blonde Pakistani women went to play badminton, dance with sleaze balls and enjoyyzz.

The JI were able to rid the land of Bhutto, but the night clubs, bars and assorted havens of vulgarity remained.

So much so, that by the time the glorious soldier of faith, Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq, brought about the much-needed moral revolution, Pakistan had become the second most vulgar country after the poor, corrupt and war-torn African republic of Holland.

The Mard-i-Momin, Mard-e-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq did everything a wise and decent Muslim leader could do to transform Pakistan into a country much like the beloved Saudi Arabia (minus the oil).

But because of the amazing discount deals offered by the Nite Keelab on its famous chicken tikka pizzas, vulgar dancing had almost become a genetic phenomenon in Pakistan.

So, logically Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq decided to take the matter by the horns and rid the country of vulgarity once and for all: He banned breathing.

For 11 years, Pakistan truly became the land of the pure. Though there were many deaths and millions of cases of sudden asphyxia and chronic asthma due to the ban clamped on breathing, but at least there was no vulgar dancing and sex education!

Unfortunately, the pure, decent and upright regime of Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq was brought to an abrupt end after a mere 11 short years.

Once again, Pakistan plunged into the darkness of vulgarity and sex education. On that fateful day, Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq was brutally murdered by the vicious Soviet spy, Boris Becker, and infamous Indian assassin, Kapil Dev, along with the clandestine owner of the Nite Keelab, Madam Najma.

1977: Owner of the Nite Keelub, Madam Najma, threatening a young Shahbaz Sharif, who wanted her to close down her evil club.

The regime that followed was of Benazir Bhutto who, being a woman, at once lifted the ban on breathing.

All hell broke loose, and in the next 10 years Pakistan even beat the African republic of Holland to become the most vulgar and obscene country with rampant free sex, steamy night clubs, bars, AIDS, VDs, STDs and worse of all, sex education in co-ed schools!

The few morally correct people who refused to send their children to these co-ed dens were punished when Christian evangelists dressed as NGO workers administered polio drops to their infants.

Everybody knows polio drops are a way to sterilise sturdy Muslim male babies from raising armies that will one day conquer the world. And the fact that sex education at schools can turn them into sissies.

NGO workers administering polio drops in Waziristan.

The heroic Ameerul Momineen, Mian Nawaz Sharif replaced Benazir and did all he could to revive the ways of his mentor, Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq.

He also tried to ban breathing, but because of the evil ways of a malicious Freemason, Asif Ali Zardari, Mian Saab’s gallant strides towards the re-purification of Pakistan were halted.

Distracted by Zardari’s suggestive disco moves, Mian Saab failed to sight a conspiracy against his just and peaceful rule. In 1999, the neo-Nazi tyrant, General Adolf Musharraf, toppled Mian Saab in a Bloody Mary coup and unleashed another wave of vulgar dancing and sex education in schools.

Under the general’s rule Pakistan again became a den of immoral activities as bars, night clubs, discos and hot dating spots and spas sprang up all over the country.

What’s more, even places like Bajaur, Swat and Waziristan weren’t spared, where the dictatorship closed down madrassahs and replaced them with Nato-run gambling dens.

The dens were run in Nato supply trucks, containers and tankers, the same trucks and containers that PTI’s gallant muscle man Shaheen Mazari has recently been running over with a Harley Davidson.

PTI’s Shaheen Mazari off to run-over Nato trucks with a motorbike.

In Swat, whiskey ran in the river where once pure water flowed. It was a painful sight. The soul of Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq turned awkwardly in his resting place and the resultant rumbling caused the 2005 earthquake in Kashmir, the 2010 floods in Sindh and the 2014 Altaf Hussain speech.

This was a sign and a warning. The word ‘repent’ rang loud in the skies of the country.

Moralistic, upright men like the peace-loving Sufi saint, General Hamid Gul; former captain of the veiled Pakistani women’s cricket team, Madam Inzi, and the hero of the 1857 Indian Mutiny, Munawar Hassan, all struggled against Mush’s vulgar dancing demons to put Pakistan back on the right path, but to no avail.

Alas, in February 2008, Musharraf was overthrown. However, this did not mean Pakistan returned to the clean, pure days of Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq.

Sindh, KP, Balochistan, Mars and Neptune went to the Freemason Zardari who took back the Nite Keelab chain from Musharraf and continued the process of turning Pakistan into one big den of vice and vulgarity.

Asif Zardari flashes the victory sign after taking over the Nite Keelub.

Women stopped wearing the veil, men shaved off their beards, cities stank of whiskey, everybody wanted to be a vulgar dancer like Mithun Chakraborty, and polio drops became freely available.

Only Punjab and Pluto fell to Mian Saab, whose brother Shahbaz Sharif has continued to sort out the obscene mess left behind by Musharraf and Zardari.

I strongly urge secular opposition parties like the PPP, MQM and ANP to take the path treaded so wisely by Mard-i-Momin, Mard-i-Haq, Ziaul Haq, Ziaul Haq and the Punjab CM Shahbaz Sharif and, of course, the Interior Minister Maulana Mujahid Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, the conquer of Bangladesh.

The ruling pious PML-N should merge with all other PML factions and form PML-ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ123 and continue to reopen madrassahs closed down by Musharraf, abolish co-education, sex education, shaving and polio drops.

But most of all, it must stop American drones from firing alcohol-laced missiles and distributing John Travolta dance manuals to the innocent shepherds of northwestern Pakistan.

The innocent shepherds hate to dance and would kill for their right to turn all of Pakistan into a proud society of righteous shepherds and obedient sheep.

I must remind our vulgar dancers and those trying to impart sex education in schools that this is Jinnah’s Pakistan, and not George ka Pakistan. Kyun, jee?

CURTSEY:DAWN.COM JAN 09, 2014

Nadeem F. Paracha is a cultural critic and senior columnist for Dawn Newspaper and Dawn.com

He tweets @NadeemfParacha